Category Archives: James Scott Bell

Don’t Be Afraid to Fail Aggressively

When you get a comment like that, one that says you accomplished what you set out to do in a book you’ve poured your heart into, it makes the whole thing worth it.

Yes, there will be dissenters. We who write professionally know that well. But while there is no sure formula for success, there is one for failure: try to please everybody.

Daniel Hadley is Down in Somerville

This submission for critique has no title, but I think it shows promise. The central character has appeal. Catch my comments on the flip side.

Excerpt

“Daniel’s in stable condition, but he’s been shot.”

I lay in bed, propped up on one elbow, the cell phone digging into my ear. I didn’t even remember it ringing. Had I passed out drunk while talking to someone? But every light in my bedroom was off, save for the pale green LCD of the alarm clock: 1:45 AM. Then the part of my brain that makes sense of words – the part that I normally can’t shut up when I’m trying to go to sleep – kicked in. “Shit,” I said, sitting upright.

“He’s stable, like I said. They’re monitoring him at Mass General.”

“Right,” I answered. “How long?” But the phone went dead.

“Fuck,” I repeated. Then I hung up and got out of bed. I padded across to the closet to pull some jeans off a hanger and yesterday’s bra out of the hamper. A tanktop and a ratty Redskins sweatshirt completed the ensemble. Ninety seconds after getting off the phone I was out the door.

Somerville’s a dense town, so I had to walk a block to where I’d parked my car. The autumn air sobered me up enough to realize I didn’t have a plan just yet. There was one detail I could check, of course. Fishing my phone back out of my pocket, I called Daniel. “Hey, this is Daniel Hadley. I’m either on the phone or -” Damn it. Is there anything longer than a voice mail greeting when you’re trying to reach someone live?

“Daniel, hey, it’s Mara,” I began. “It’s 1:50 A.M. on, uh, Tuesday. Listen, I just got this really strange call that said you were … um. Please call me as soon as you get this, if you’re okay. If you’re not, well …”

I cut myself off there, shutting the phone and fumbling for my keys. I hadn’t fully processed the news yet (Daniel had been shot; holy hell; fatigue and shock kept shoving that detail to the back of my mind, like a rookie hockey player hitting the boards).

Comment Summary on “No-title” Story:

Generally I like the voice of this woman character. She comes across as a no nonsense person who could sustain a reader’s interest with the uniqueness of her character’s attitude and her low key fashion sense. And her attachment to alcohol could prove to be interesting as baggage. But rather than starting out with the dialogue line (as I explain my objection below), I might start out with how this woman feels getting the shock of the cell phone ringing her out of her drunken stupor. No one likes getting calls in the middle of the night. It’s a relatable moment most readers will understand. These calls are NEVER good news. And establishing this character from that moment might also help in creating her “voice” and her attitude more fully from the get go.

This is a personal preference, but I wouldn’t begin a novel with a dialogue line because it feels too much like the start of any other scene. An intro dialogue line into a scene can be effective and I’ve done it, just not for the start of a book. And whoever is speaking needs to be identified in some fashion, even if it’s just someone generic, like “dispatch.” Try to ID the person as soon as you can after the dialogue.

And speaking of identification, when you write in first person, you need to ID the speaker’s gender in some way as soon as you can. The reader will get an idea in their head—like I did that the narrator is a man—who is a cross dresser, when he reaches for yesterday’s bra from the hamper. I’ve done this before too. (The name of my character was a gender neutral name and was supposed to be a teen girl. But when my beta reader read the passage, she thought it was a teen boy who was checking out another guy’s wranglers. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it wasn’t my intention.) Once you write a first person POV story, you notice things to watch for. And gender at the start of a book is one of them.

I’m writing a YA book now where I have two teens speaking in first person. I identify them by using their names at the top of each scene and try to have one character per chapter where possible. It makes sense for this book and I like writing challenges.

I also wasn’t sure I understood Mara’s question – “How long?” Is this her entire question? If this was intended to be a question cut short, then add punctuation like a dash to indicate this. “How long—?” or “How long…?”

And if the line goes dead, it takes a while before anyone to notice, but in this scene, the character knows immediately. If the line goes dead, make it more realistic by her rambling until she hears dial tone and gets frustrated.

Also, if you have only one character in the scene, I would try to minimize the use of tag lines identifying her. You should ID the person on the phone, but after that, there isn’t a need to clutter the scene with unnecessary tag lines like ‘I answered, I repeated, I began.’ There are four tag lines in a short segment of a scene with only one character in it after the phone goes dead.

And finally the last paragraph. The punctuation seemed odd to me and pulled me from the story. I’ve never liked the use of semi-colons. Break apart the sentence into fragments if you have to, but resist the semi-colon, especially when the character has the informal attitude this one has. (What do the rest of you think about semi-colons—readers and authors? Copy editors try to put them in and I take them out, making other changes that are more my preference.) See James Scott Bell’s post on semi-colons HERE.

I also rarely use parenthesis, except in my YA books where it can be fun to use sparingly. I prefer em-dashes for emphasis, as shown below.

And the use of the metaphor on hockey—“…fatigue and shock kept shoving that detail to the back of my mind, like a rookie hockey player hitting the boards”—didn’t seem to fit when she was referring to such a serious event as someone getting shot. It makes her sound flip about something that should be more important to her. Also, she’s a Redskins fan AND a hockey fan? I’m sure this is possible, but in one short scene, it seems excessive. You may get more mileage if you made her a super fan of one sport when it comes to her metaphors, rather than spreading her enthusiasm over many.

Even though this scene could be written better, it shows promise with a compelling character voice. I would also consider starting the novel with something else that happens prior to this scene—like maybe Daniel’s shooting. If this is crime fiction, I like to start with a crime. And I’ve also found that you can always go back to write that action scene after you’ve started the book to get a feel for the story and its characters. It might help to know Daniel before you shoot him, for example. (Wow, that sounded awful.)

Any other helpful comments for this author?

Going E

Happy Holidays!

It’s Winter break here at the Kill Zone. During our 2-week hiatus, we’ll be spending time with our families and friends, and celebrating all the traditions that make this time of year so wonderful. We sincerely thank you for visiting our blog and commenting on our rants and raves. We wish you a truly blessed Holiday Season and a prosperous 2011. From Clare, Kathryn, Joe M., Nancy, Michelle, Jordan, John G., Joe H., John M., and James to all our friends and visitors, Seasons Greeting from the Kill Zone.

It’s Winter break here at the Kill Zone. During our 2-week hiatus, we’ll be spending time with our families and friends, and celebrating all the traditions that make this time of year so wonderful. We sincerely thank you for visiting our blog and commenting on our rants and raves. We wish you a truly blessed Holiday Season and a prosperous 2011. From Clare, Kathryn, Joe M., Nancy, Michelle, Jordan, John G., Joe H., John M., and James to all our friends and visitors, Seasons Greeting from the Kill Zone.

See you back here on Monday, January 3.

Strategies for surviving the epublishing revolution

One of the perks of being Program Chair of MWA, SoCal is that I get to do outreach to interesting, dynamic people. On Saturday we had a very cool panel at our chapter meeting, including Marci Baun, publisher of Wild Child Publishing, and our own Jim Bell. Author Gary Phillips moderated the program, which was called, “Epublishing: Will it help your career, or kill it?”

Gary opened the discussion by citing some statistics: Today, epublishing is still a relatively small slice of the publishing world, but it’s growing exponentially. Baun, whose company is an innovator in the epublishing market, started off by setting aside the “myth” that publishers see huge savings by publishing e-books instead of paper. (Gary has since alerted us to a NYT article on the same topic, Math of Publishing Meets the E-book.) Jim also fielded some questions about TKZ’s new e-book anthology, Fresh Kills.

The panelists stressed that to be successful in any kind of publishing, especially epublishing, it’s important to do social networking. Blogging, Facebook, Twitter: You have to get your name out there and work your networks. At one point they asked for a show of hands from the people who are active social networkers; many hands went up, but not a majority. I was surprised by that–I would have assumed that almost everyone in that group would be active online. Around the lunch table, I heard some people say that they find social networking to be confusing and intimidating.

A small but consistent networking effort can be very effective according to Baun, who said she requires an author to make a successful online marketing effort before she’ll launch a print run for their book.

The panel discussed the do’s and don’ts of social networking, including the importance of adding value to the discussion, and avoiding endless BSP. Among the strategies discussed were What to Tweet, and using ebooks as a loss leader. After the meeting I followed Jim’s suggestion to use Tweetdeck, and to get more actively involved in forum discussions.

Other than doing my weekly blog posts, I’ve been hit or miss in my social networking efforts up until now. As a result of Saturday’s meeting I’ve resolved to spend at least 15 minutes a day making the networking rounds.

What about you? How much time do you spend social networking every day, and are you consistent?

Short Stories Matter

As you know, we’ve been celebrating the release of Fresh Kills here on TKZ. It’s been a pleasure working with my blogmates, pros all, to bring you these new stories, at an attractive price. Look for Fresh Kills at amazon, scribd or smashwords.

My contribution to the anthology is “Laughing Matters,” a title that has more than one meaning, as you’ll find out. And that’s sort of what the best short stories do; they work on at least a couple of levels.

Certainly, the literary short story is like that. In college I got to take a writing workshop with Raymond Carver, and that’s what his stories are famous for. They have something going on up top, on the surface, but when you finish you realize there’s a rich layer underneath that you’ve missed (and I have to confess, I usually did, and would have to re-read each one a couple of times).

In the suspense or mystery category, you need to deliver a story that has a surprise in it somewhere, to keep the reader guessing. Jeffery Deaver has written two volumes of such tales in his Twisted series, and even challenges the reader to try to outguess him. It’s cool when it works, but it’s hard to do. Which is why this kind of story is every bit as challenging as the literary sort.

The germ of “Laughing Matters” came one day when I was thinking about all the standup comics in LA who never make it. I must have just seen some clip of a comedian doing post-Seinfeld observational humor (one of thousands) and just thought, this is dull. This is derivative. This guy’s not going to go very far.

Which reminded me of a time when I was living and acting in New York, and went to a comedy club for “open mike.” There were some funny guys, and then there was this one kid who was obviously onstage for the first time. The sort whose grandmother must have told him, “Sonny, you are so funny! You should go tell your jokes on television!”

Anyway, the kid comes out, he’s nervous, and tells a joke. It fell to the ground with a thud that echoed through the club. He got rattled. And you know what happens when you get rattled in front of the 11 p.m. crowd in New York City on open mike night? It was brutal. The kid made it through maybe two more jokes, neither of which worked, and then froze. As the crowd piled on with jeers and snorts, he stood there, choking the mike stand, unable to move or speak.

The emcee, noting what was going on, jumped in from the wings with his big smile, clapping his hands, shouting “Let’s hear it for _____ !” and then took the guy’s arm and guided him off the stage.

There must have been public hangings easier to watch.

So all of that came to me as I wrote the opening lines:

He died.

Pete Harvey, “The Harv” as he billed himself, just flat out died in front of the 11 p.m. crowd at the Comedy Zone.

Then I have Pete sitting at the bar afterward, drowning his sorrows, when a most interesting gent sits down next to him. And the story came to me in a flash, twists and all. This is, I’d wager, how the best short stories usually appear. But then you write, re-write and polish, and hopefully come up with something that works.

I’ve reclaimed my love of the short story, and have decided to keep writing them. Maybe I’ll put out my own collection sometime. It’s nice to have a market for stories again. Because short stories matter, it seems to me. A good story can deliver a hugely satisfying reading experience in small span of time.

FWIW, here are some of my favorite short stories, based on the wallop I felt at the end:

“Hills Like White Elephants,” Ernest Hemingway

“Soldier’s Home,” Ernest Hemingway

“The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze,” William Saroyan

“A Word to Scoffers,” William Saroyan

“A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” J.D. Salinger

“The End of the Tiger,” John D. MacDonald

“Chapter and Verse,” Jeffery Deaver

Tomorrow, we return you to your regularly scheduled blog. It’s been a pleasure to offer you our wares in Fresh Kills. Thanks for taking us for a spin.

First Person Boring

I love a good First Person POV novel. I love writing FP myself. But there are perils, and if you’re thinking of trying your hand at it you’re going to need be aware of them.

One of these is the “I’m so interesting” opening that is anything but.

Recently I read a couple of novels in FP that had this problem. They began with the narrator telling us his name and giving us a chapter of backstory. By the time I finished the opening chapter I was thinking, Why am I even listening to you?

Let me illustrate. You go to a party and see a guy standing off to the side, you nod and introduce yourself, and he says, “Hi. My name is Chaddington Flesch. Most people call me Cutty, because my grandfather, Bill Flesch, refused to call me anything else. He liked Cutty Sark, you see, and thought this name would make a man out of me. All through school I had to explain why I was called Cutty. Growing up in Brooklyn, that wasn’t always easy. Even today, at my job, which happens to be as an accountant, I . . .”

Yadda yadda yadda. And you’re standing there at this party thinking, Dude, I’m sorry, but I don’t especially care about your history. I have a history, everybody at this party has a history. Nice meeting you, but . . .

But what if you introduce yourself to the guy and he says, “Did you avoid the cops outside?”

You look confused.

“Because I got stopped by a cop right out there on the street. He tells me to hit the sidewalk, face down, and then proceeds to kick me in the ribs. I say, ‘There’s been a mistake.’ He gets down in my face and says, ‘You’re the mistake. I’m the correction.'”

What are you thinking then? Either: Am I talking to a criminal? Or, What happened to this poor guy?

What your reaction isn’t is bored.

You are hooked on what happened to him. And that’s the key to opening with FP. Open with the narrator describing action and not dumping a pile of backstory.

Save that stuff for later.

Open with movement, with action.

I got off the plane at Maguire, and sent a telegram to my dad from the terminal before they loaded us into buses. Two days later, the Air Force made me a civilian, and I walked toward the gate in my own clothes, a suitcase in each hand.

I was a mess.

[361 by Donald Westlake]

The girl’s name was Jean Dahl. That was all the information Miss Dennison had been able to pry out of her. Miss Dennison had finally come back to my office and advised me to talk to her. “She’s very determined,” my secretary said. “I just can’t seem to get rid of her.”

Then Miss Dennison winked. It was a dry, spinsterish, somewhat evil wink.

[Blackmailer by George Axelrod]

The nun hit me in the mouth and said, “Get out of my house.”

[Try Darkness by James Scott Bell]

Now I realize I’ve used hardboiled examples here, and some of you favor more literary writing. There’s a lot of debate on just how you define “literary,” but let me suggest that literary does not have to mean leisurely. You can still open with a character in motion in a literary novel, and I guarantee you your chances of hooking an agent or editor, not to mention a reader, will go way up without any other effort at all.

One of my biggest tips to new writers is the “Chapter 2 Switcheroo.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve looked at a manuscript and suggested that Chapter 1 be thrown out and Chapter 2 take over as the new opening. I would say, conservatively, that 90% of the time it makes all the difference, because the characters are moving. There’s action. Something is happening. And truly important backstory can be dribbled in later. Readers will always wait patiently for backstory if your frontstory is moving.

Try it and see.

The Liar’s Club

No really, you shouldn’t have. I mean, sure, it is our…

ONE YEAR ANNIVERSARY!

What do you mean, you forgot? Yes, it was just a year ago today that I wrote the inaugural post for The Kill Zone. And to celebrate a year of rants, raves, and other miscellany, my fellow bloggers and I decided to do what we do best- make stuff up. Below is a series of questions. One of the answers to each question is an outright, baldfaced lie. Your job is to guess who’s fibbing.

For each correct guess, your name will be entered in a drawing for signed editions of each of our latest releases (including my coffee table book on macrame. It’s not just about macrame, it’s MADE of macrame. Patent pending).

Because after all, what anniversary would be complete without fabulous gifts?

Note: despite the outrageous nature of some of these responses, there is only one liar per question. Hard to believe, but true. The winner will be announced in my post next Thursday.

So good luck, and thanks for making this an amazing year!

1. What’s the most “outrageous truth” about yourself, one few people would ever guess?

Kathryn: I once hid in the bushes outside Ted Kennedy’s home, spying on him for a Boston TV station.

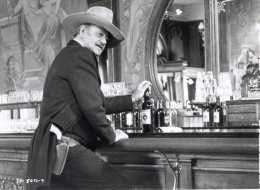

John Gilstrap: I was featured in John Wayne’s last filmed performance.

Clare: I was runner up in the 1989 “Miss Melbourne” beauty pageant.

James: I’m a descendant of the Duke of Wellington

Michelle: I was a featured guest on the Maury Pauvich show.

2. What’s the strangest interaction you’ve ever had with a fan or reader?

James: A man approached me at a conference and said God told him I was chosen to write his story. I told him I didn’t get the memo.

Clare: During an radio interview for Consequences of Sin, the host claimed he had predicted 9/11.

Michelle: At a conference, a Ted Kaczynski look-alike handed me a manila envelope filled with xeroxed diary pages outlining ominous apocalyptic predictions.

John Gilstrap: After giving 20 minutes of advice to a young writer at a signing, he walked away saying, “Huh. Well, I don’t read shit like you write.”

John Ramsey Miller: In 1997 I had a stalker who followed me on a book tour to 5 cities out of 11. She changed her appearance each time and asked me to sign a book to whatever name she was disguised as.

Kathryn: During a radio interview for DYING TO BE THIN, one caller claimed there is a conspiracy to keep America fat. I said thank goodness for that, otherwise I’d have to blame my sweet tooth.

3. What’s the craziest/most dangerous thing you’ve ever done in the name of research?

John Gilstrap: I intentionally leaned against a prison fence and walked around the perimeter to see how long it would take for a guard to respond.

John Ramsey Miller: In the mid to late eighties I set up a formal portrait studio at a series of KKK rallies across the south and at the Annual Celebration of the Founding of the Ku Klux Klan in Pulaski Tennessee.

Kathryn: I logged onto wild and wooly web sites that gave my computer a nasty virus.

Kathryn: I logged onto wild and wooly web sites that gave my computer a nasty virus.

Michelle: I volunteered to be tased to see what it felt like.

James: I asked Chuck Norris to show me his Total Gym workout

Clare: I navigated piranha infested waters in a dugout canoe.

4. What’s the worst line you’ve ever read in a review or rejection of your work?

John Gilstrap: An agent offered to represent NATHAN’S RUN if I would change the protagonist from a 12-year-old boy to a divorced woman.

Joe Moore: “Weak and simple plot, unbelievable and boring characters, and poor writing make this book difficult to finish.”

James: Dear Mr. Bell: Enclosed are two rejection letters; one for this book, and one for your next book.

Kathryn: Agent rejection: “I really wanted to like your story. But I just didn’t like the voice. Or the main character. I just didn’t like anything about it at all.”

Clare: “It’s painful to read more than one or two pages at a time.”

I have to say, I was impressed with my fellow bloggers’ ability to lie with aplomb. Since I could only choose one lie per question, I was forced to omit some real humdingers. Next week I’ll include outtakes/elaborations in the post.

On a side note, Clare just officially became a US citizen (and that’s the truth). Welcome and congratulations!

Serendipity

Today is July 26, a day of celebration for me. For one thing, it marks my debut on The Kill Zone, and I couldn’t be more pleased to be included with six writers I admire. I’ve learned a lot from this august company, and am proud to be added to the mix.

This date also happens to be one that changed my life forever—for it was on July 26, 1980, that I met my wife.

I was at a birthday party for a friend. It had spilled out into the courtyard of his apartment building, where I sat at a table with a couple guys, yakking. I happened to look up and saw a blond vision of loveliness heading up the stairs to the apartment. I turned to my comrades and said, “I’ll see you later.”

I got to the apartment just as she was hugging my friend. Her back was to me. I silently motioned for my friend to introduce me. And that, as they say, was that. I fell like five tons of brick and mortar. It took me all of two-and-a-half weeks to ask her to marry me. (Perhaps this explains why I favor first page action in my books). Eight months later we were wed and my life has been richly blessed ever since (in no small part due to Cindy’s sharp editorial eye; she’s always my first reader).

When I think of these events, the word serendipity comes to mind. It’s a word derived from a Persian fairy tale, The Three Princes of Serendip (an ancient name for Sri Lanka). The story tells of an eminent trio making happy discoveries in their travels, through accident and observation. The English writer Horace Walpole coined the term serendipity to describe this combination of chance and mental discernment.

Which is a long way of saying that some of the best things that happen to us in life are “happy accidents” because we’ve shown up, and are aware.

Much of the best writing we do is serendipitous, too. As Lawrence Block, the dean of American crime fiction, put it, “You look for something, find something else, and realize that what you’ve found is more suited to your needs than what you thought you were looking for.”

Doesn’t that describe some of the best moments in your writing? I once had a wife character who was supposed to move away for a time, to get out of danger. That’s what I’d outlined. But in the heat of a dialogue scene with her husband, she flat out refused to go. Turns out she was right and I was wrong, and the story was better for it.

Can we ramp up serendipity as we write? I think so. Here are a few suggestions.

Don’t just be about imposing your plans on the story to the detriment of happy surprises. Be ready to shift and move.

The way of serendipity is open to every writer, be you an outliner or a seat-of-the-pants type, or anything in between. It’s just a matter of showing up and being aware. And the more you write, the more you’ll recognize serendipitous moments when they arise.

Has serendipity played a role in your own writing? Tell us about it.

And thanks again to The Kill Zone for the invitation. A happy surprise indeed.