“at sea” – an idiom meaning “confused” or “lost”

* * *

I recently read a book entitled Longitude by Dava Sobel. It’s the story of an invention that first made it possible for sailors to pinpoint their location at sea. According to Sobel,

“Lines of latitude and longitude began crisscrossing our worldview in ancient times, at least three centuries before the birth of Christ. By A.D. 150, the cartographer and astronomer Ptolemy had plotted them on the twenty-seven maps of his first world atlas.”

Knowing one’s position on the face of the earth is just a matter of knowing the latitude and longitude. . (You’ll remember latitude are the horizontal lines around the earth, all parallel to the equator. Longitudinal lines (meridians) are lines drawn from the North Pole to the South Pole.)

During the Age of Exploration, roughly from the 15th to the 18th centuries, one of the major seafaring problems was the inability to establish the ship’s position on the high seas. Latitude was fairly simple to determine by the height of the sun as it progressed across the sky or by the position of certain stars, but there’s no similar way to determine longitude. Once a ship sailed out of the sight of land, it had no reference point for which to understand its east/west position.

Since longitude is a measure of time, not distance, an easy way to determine it is to compare the time of day on board ship with the time at the home port from which the ship sailed. This can be accomplished by setting a clock to the home port time before sailing and keeping that clock on the ship. The actual time aboard the ship is determined by the position of the sun and compared to the clock. Each hour of difference corresponds to fifteen degrees of longitude. Sounds easy, right? Unfortunately, there were no clocks in existence during the early days of the great explorers that would keep accurate time on board a ship. The movement of the ship and the changes in temperature, pressure, and humidity affected the clocks’ mechanisms, and the results were unreliable.

Some of the best minds of that era, including the great Sir Isaac Newton, had tried to find an astronomical solution to the problem, but the quest seemed out of reach. (Pun intended.)

It was such a big problem that in 1714 the British Parliament passed the Longitude Act which offered a lucrative prize for the first person who could deliver a practical means of determining longitude at sea.

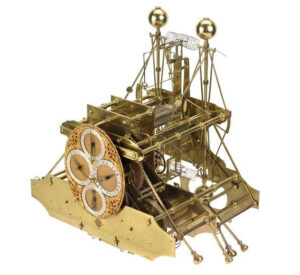

Into this environment stepped John Harrison, a carpenter and self-taught clock maker, whose skill and determination were just the attributes needed. Harrison solved problem after problem in his dogged persistence, and finally in 1736, his first clock, unimaginatively named the H-1, sailed aboard the HMS Centurion to Lisbon and returned aboard the HMS Orford. The clock performed admirably, and the Longitude commissioners asked Harrison to continue his work.

Over the course of the next twenty-five years or so, John Harrison created a total of three more clocks. The fourth one (you can guess the name: H-4) was actually a watch, and it was the H-4 that sailed to Jamaica in 1765 and performed within the limits required by the Longitude Board for the prize. John Harrison had solved one of mankind’s thorniest problems, and he likely saved the lives of many sailors in the process.

John Harrison is revered in England for his work. All four of his sea-faring clocks reside in the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England. In 1884, the Prime Meridian (longitude 0°) was defined as the longitudinal line that runs through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. Hence, our definition of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) from which all other time zones are offset. If you visit the Royal Observatory, you can have your picture taken astride the Prime Meridian, one foot in each hemisphere.

* * *

As I was reading about the longitude problem, I couldn’t help but notice the similarity to writing. PJ Parrish quoted Walter Mosley in her Kill Zone Blog post last week:

Writing a novel is like taking a journey by boat. You have to continuously set yourself on course. If you get distracted or allow yourself to drift, you will never make it to the destination.

So how do we as authors keep ourselves on course? It’s easy to feel like you’re “at sea” when you’re in the second act muddle, not sure how to get to your destination, or even exactly where your destination lies. But there are experts who can help us find our writing longitude. I have a stack of craft books I love to refer to. Here are a few:

- Plot and Structure by James Scott Bell

- Self-editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne and Dave King

- Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

- Fire Up Your Fiction by Jodie Renner

- Writing Novels That Sell by Jack M. Bickham

- Techniques of the Selling Writer by Dwight V. Swain

- On Writing by Stephen King

* * *

So TKZers: What resources do you use to chart your course across the great ocean of writing a novel?

And speaking of time …

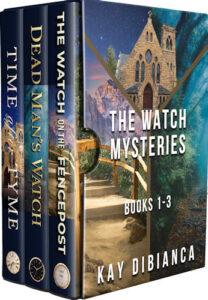

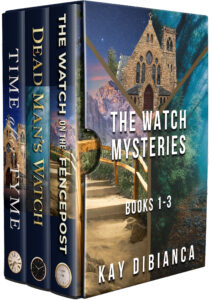

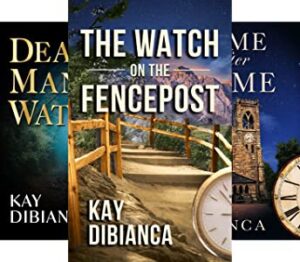

The Watch Mysteries is a box set of three complete novels in which clocks, watches, and time play an important role.

If you’re having trouble posting a comment, please be patient and keep trying. We’re sorry for the inconvenience, but we’re having technical problems and we’re working to resolve them.