It’s been a while since I’ve written any gun porn. This is the day the drought ends.

Here’s the scenario: Your character, Detective Dan, knows that he is marching into harm’s way to confront at least two bad guys who he knows are armed. For our purposes here, Detective Dan is part of a small force, maybe just a partner or two. The smart move is to wait for backup, but they can’t do that because a family of four is being held hostage and things have gone very bad very quickly.

It’s almost certain that shots will be fired. The good news is they have a pretty good arsenal to choose from. Just to make it interesting, they have to walk a long way to get in an out, and climb a lot of stairs. And let’s put them in regular street clothes–nothing tactical. Think business suits.

Choose Your Weapons

Simunitions are essentially medium-velocity paint pellets that can be loaded into real weapons. Yes, they sting when they hit.

There’s an adage among the tacti-cool crowd that the only reason to carry a pistol is to fight your way back to your rifle. Having never been in a real gunfight I can’t speak to the veracity of the adage in the real world, but my experience having been a bad guy in Simunitions training with law enforcement agencies, I can attest to feeling woefully outgunned when I brought my 15-round Glock into play against their 30-round M4s.

If I’m writing Detective Dan, he’s going to want to have a rifle with him. If his police agency is like most that I know, he’s got an M4 stashed in the trunk of his car, right next to his ballistic vest. An M4 is the rifle you see in most pictures of soldiers and SWAT team operators.

Right about now, when he’s kitting up for the fight, Detective Dan is going to second-guess his decision not to wait. That vest he’s putting on will stop most pistol rounds, but it’ll be useless against a rifle bullet. In an hour, he could have the State Police there with ballistic shields, dogs and a helicopter. Best of all, he’d have a team that’s specifically trained to do the kind of entry that he’s about to attempt.

Right about now, when he’s kitting up for the fight, Detective Dan is going to second-guess his decision not to wait. That vest he’s putting on will stop most pistol rounds, but it’ll be useless against a rifle bullet. In an hour, he could have the State Police there with ballistic shields, dogs and a helicopter. Best of all, he’d have a team that’s specifically trained to do the kind of entry that he’s about to attempt.

But hey, he wouldn’t be the main character in a book if he didn’t put his life on the line from time to time.

Now, Detective Dan has some thinking to do. Of the weaponry available to him, what should he take?

Everything is heavy.

A Glock 19 (common pistol for police agencies around the world) loaded with a standard 15-round magazine weighs about two pounds. Extra mags weigh a half pound apiece. Detective Dan normally carries two extra mags, so that’s three pounds on his belt. It’s no wonder so many detectives wear suspenders.

His loaded M4 weighs 8.5 pounds and each extra 30-round magazine weighs about one pound. Detective Dan decides to carry four extra mags to feed his M4. The good news here is that his vest–which itself weighs 5 to 8 pounds (or more)–has pouches specifically designed to hold extra mags with that weight distributed across his shoulders.

Detective Dan will use a single-point sling for his M4 to help distribute that weight, as well. Then there’s the radio, handcuffs and whatever other hardware Detective Dan carries. All of it bounces around and rattles when he moves.

Tough choices.

Does Detective Dan really need 45 rounds for his pistol and 150 rounds for his rifle? This mission would be a lot lighter if he cut back on ammo. And he’d sweat a lot less without the body armor. Suppose the fight degenerates to hand-to-hand? He’s going to have a heck of a time maneuvering with all that stuff on him.

As the author, you have to balance what is reasonable for the character. If you’ve established Detective Dan as a reformed alcoholic 50-something with a beer gut, the choices are much different than if you’ve established him as a 30-something ex-Special Forces operator who works out two hours a day.

The last thing Detective Dan wants is a fair fight.

If Detective Dan had had the gift of time, he could have waited for darkness to fall and brought night vision into play as a force multiplier. In any confrontation, when your team is the only one that can see anything, the odds of winning tilt decidedly in your favor. In the real world, there are no verbal warnings, and no warning shots. When a bad guy points a firearm at a good guy, there’s going to be a gunfight. More times than not, the shooter with the most training wins, and the loser is dead. In that engagement, the trained shooter will aim exclusively at the bad guy’s head, torso or pelvis, because that’s where the major organs and blood vessels are. If someone is hit in the leg or the hand, that’s because the trained shooter whiffed that shot.

Shots fired.

I don’t want to write a whole scenario here, but let’s talk about some practical considerations. We’ve kitted out Detective Dan with lots of cool options, so when the shooting starts, he and his team can have the best possible chance of seeing dinnertime.

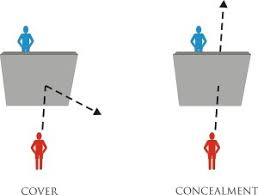

Once the SHTF (come on, you can figure that one out), Detective Dan does not have the luxury of panicking. He needs to be keenly aware of the differences between cover (which prevents being hit by bullets) and concealment (which merely makes him invisible). He needs to remember that he is responsible for every bullet he sends downrange, and that the four innocents are as susceptible to his gunfire as the unknown number of bad guys.

Once the SHTF (come on, you can figure that one out), Detective Dan does not have the luxury of panicking. He needs to be keenly aware of the differences between cover (which prevents being hit by bullets) and concealment (which merely makes him invisible). He needs to remember that he is responsible for every bullet he sends downrange, and that the four innocents are as susceptible to his gunfire as the unknown number of bad guys.

Every shot needs to be aimed at a known target. And because Detective Dan is a dedicated professional, he won’t take even the perfect shot if one of the hostages is in the background and likely to get hit. More on that later.

The bad guys, by contrast, don’t care who they kill, so they can feel free to shoot blindly.

Rifle or pistol?

The distance between the front sight and the rear sight is called the sight radius. The longer the radius, the more accurate the shooter.

There are many reasons why most people (everyone I know) shoots more accurately with a rifle than with a handgun, but mostly it boils down to the stability of the platform and the sight radius (the distance between the front and rear sights). Holding a firearm against your shoulder is inherently more stable than holding one out at arm’s length. That’s true of holding anything, right?

Past 15 yards for most shooters, and 25 yards for all but the most elite competitive shooters, a pistol shot is at least equal parts hope and marksmanship. For that M4 Detective Dan is carrying, accuracy at 100 yards isn’t even a challenge if he’s had even a little bit of training.

Here’s the problem: Those rifle bullets love to fly. That head, torso or pelvis it hit is just the beginning of its journey. The bullet might break up, it’s trajectory will probably will destabilize and it might start tumbling, but it will still be going very fast. The next few milliseconds could get troubling for others in the room. Perhaps that’s not a concern if everybody in the room is a bad guy, but that’s not our scenario. Again, those pesky hostages are the wildcard.

Given the weaponry he carries, Detective Dan must always weigh accuracy against collateral damage. I imagine it will be stressful for him.

I cheated a little to make a point.

I gave Detective Dan weaponry he most certainly would have access to, but not necessarily his smartest choices.

The M4 I gave Detective Dan is the weapon that every cop seems to be carrying on the news during active shooter incidents. I saw a DC subway cop carrying one on a train not too long ago. It’s tacti-cool as all get out–makes for a badass photo op–but I think it’s the wrong gun.

If I were Detective Dan, I think I’d have taken a 12 gauge shotgun as my long gun. I’ve rarely seen a police vehicle that doesn’t have one, and it is a very effective weapon in close quarters, with less chance of over-penetration.

A lot of police agencies employ a hybrid weapon called a pistol caliber carbine. The Uzi and Heckler and Koch MP5 are probably the most famous of these. Certainly, they are heralded by Hollywood. Also called personal defense weapons (PDWs), pistol caliber carbines provide the stability of a longer frame with the ballistics of a pistol.

Critics (and every tactical operator I know) argue that pistol caliber carbines are overrated. Why carry two pistols? If the bad guy has body armor, the good guys’ advantage is reduced. A load of 00 buckshot probably would not penetrate body armor either, but getting hit with all 9 of those .32 caliber pellets would probably take their breath away long enough for a second shot.

Okay, it’s late and I’m tired. We’ll talk about tactical reloads and deeper tactical considerations later. Questions and comments are all welcome.