By John Gilstrap

Another brave anonymous writer has submitted a first page for review and comment. Y’all know the drill by now: First the piece, and then comments on the other side. NOTE: The italics are all mine, a way to differentiate whose writing is which.

THE HALCYON VENGEANCE

Adrian Steele stared out the 10th floor window in the direction of Sheremetyevo. Snow drifted lightly down. His jaw clenched. He was in Moscow. In winter. Again. He glanced over to Natalya who recited the final brief for his assignment in Cuba. Steele kept his expression neutral, his impatience hidden. He traced a finger through the condensation of his breath on the cold window. His hand remained steady. Good. He wasn’t nervy.

“Steele,” Natalya said softly after a pause, “please remember why you’re here.”

“You’re sounding like Pierce. Doesn’t suit you.”

Natalya grimaced, stepping to the knapsack she’d left on the chair. She handed him an unmarked envelope.

“That’s all there is. It could be my job for helping you. Especially with this.”

“Clothes?”

She tossed him the knapsack. “No trackers, I checked them myself.”

Steele thought about the trackers that she’d doubtlessly put in.

Natalya turned her head to the dark window as he changed his clothes. She’d watched him before. Now she wouldn’t. He’d need to lose the clothes, then.

After he pulled on a thick parka she handed him a battered ushanka.

“Remember, flaps up. Or you’ll look like a pussy,” she muttered.

Steele nodded. He knew.

“And don’t die. Or get wounded. You need to be back by 0300 for your flight to Havana.”

He put his hand out. Natalya bit her lip as she passed him a Makarov PM and two magazines.

“Don’t fret, I won’t leave a mess.”

“You’re lucky, going to a tropical place,” she muttered wistfully.

“I wouldn’t exactly call it lucky.”

“But the weather’s better.”

“Yes, it is. Spasiba do svidaniya myshonok,” he muttered as he opened the door, checked the hallway, and slipped away.

Natalya pulled the mobile from the inside pocket of her jacket. “Did you get all of that?” she asked Pierce.

“Yes. But he lied, our Adrian did.”

“You mean –?”

“Oh, he won’t miss his flight, he knows what’s on the line.”

“But he’s off the leash…”

“I let him do this, or he won’t do the job in Cuba. He’s the only one who can and he knows it. I’m not sure what he’s got planned, but it’s going to leave a hell of a mess.”

“Will he kill Voschenko?”

“He wants to. Thank you for your help Natalya. You should go to ground.”

“But…”

“Leave myshonok. Disappear. Now.”

It’s Gilstrap again. First, by way of full disclosure, I had some real formatting issues transferring the original email onto the blogging platform. So, Anon, if I screwed up any of the paragraph breaks, I apologize.

First, the positives. I like the tone of this story. It has a very Cold War Ludlum feel to it. No one trusts anyone. I like that stuff. I also like the flow of the dialogue for the most part. It feels like a real scene, populated with believable characters.

On the downside, I have some quibbles with the prose, which I’ll discuss below, but the most urgent issue here is the fact that it’s confusing. So, let’s get to all of that.

First things first: I hate the title. It doesn’t mean anything. Titles are supposed to draw a reader in. It’s among your most important marketing tools.

Now let’s go section by section:

Adrian Steele stared out the 10th floor window in the direction of Sheremetyevo. Snow drifted lightly down. His jaw clenched. He was in Moscow. In winter. Again. He glanced over to Natalya who recited the final brief for his assignment in Cuba. Steele kept his expression neutral, his impatience hidden. He traced a finger through the condensation of his breath on the cold window. His hand remained steady. Good. He wasn’t nervy.

I get that it’s not my place to rewrite Anon’s work, but I think the opening line should be “Adrian Steele was in Moscow. In winter. Again. He stared out the 10th floor . . .” More people have heard of Moscow than have heard of Sheremetyevo, so the quicker you anchor the reader’s head to the setting, the better off you’ll be.

Anon, I urge you to cleanse your work of -ly adverbs. “Snow drifted lightly down” implies that snow can “drift” through the air heavily. In this case, the word, drift, is strong enough to carry the entire image you’re looking for.

The image of Steele tracing his finger through the condensation implies to me that he is very close to the window, yet he’s receiving a mission brief. This confuses me. Is there something outside that he must watch? Is there a reason for him not to be fully engaged in what Natalya is telling him?

This is the paragraph where the confusion starts. An assignment in Cuba could be a job as a missionary as well as an assassin. I think you should plant something more specific as to the nature of what he’s going to do, just so the reader can get his head in the right place.

“Steele,” Natalya said softly after a pause, “please remember why you’re here.”

More confusion for me. Natalya’s admonition seems unearned. To me, there’s no indication that he’s not remembering why he’s there. It doesn’t help that we the reader don’t know, either.

“You’re sounding like Pierce. Doesn’t suit you.”

A one-sentence explanation could clarify who Pierce is. Alternatively, Natalya could respond with a pithy remark like, “Impossible. His voice is much higher than mine.” Anything that would give us a hint of character.

Natalya grimaced, stepping to the knapsack she’d left on the chair. She handed him an unmarked envelope.

Here again, the grimace feels unearned. Is she in pain? As she steps to the knapsack, where is she stepping off from? In my mind, they were sitting, so she would have to rise before she steps. We need more description of the setting.

If she’s briefing him, why is the knapsack someplace other than where she is?

“That’s all there is. It could be my job for helping you. Especially with this.”

Until this line, I thought Natalya was the boss. Also, shouldn’t there be some reaction from Steele? A few lines later, we learn that he’s confident that she’s a liar, so it makes sense that he wold have some kind of cynical reaction to her fear that she might lose her job. Given that Steele is risking his life, wouldn’t he be a little bit snarky, if only in his head?

“Clothes?”

She tossed him the knapsack. “No trackers, I checked them myself.”

Here we have back-to-back non-sequiturs (sp?). Steele asks a one-word question and Natalya gives a non-responsive response. Is Steele naked? What does he need the clothes for? Is he asking if clothes are in the knapsack?

Steele thought about the trackers that she’d doubtlessly put in.

Yes! I like this bit. I’m not fond of the word, doubtlessly, but the sentiment works.

Natalya turned her head to the dark window as he changed his clothes. She’d watched him before. Now she wouldn’t. He’d need to lose the clothes, then.

More confusion. Changing clothes from what to what? Why? That she’d seen him without clothes implies that they are (or were) lovers, so why turn away? Again, this seems unearned.

After he pulled on a thick parka she handed him a battered ushanka.

I have no idea what a ushanka is, so therefore I have no image. Without an image, the next line makes no sense.

“Remember, flaps up. Or you’ll look like a pussy,” she muttered.

Steele nodded. He knew.

He knew what? That he’d look like a pussy?

“And don’t die. Or get wounded. You need to be back by 0300 for your flight to Havana.”

This is the best line of the entire piece. I would break it into two parts, though:

“And don’t die. Or get wounded.”

“I can’t,” he said. “I’ve got an 0300 flight to Havana.” He put . . .

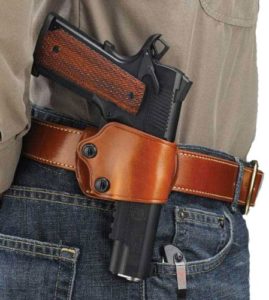

He put his hand out. Natalya bit her lip as she passed him a Makarov PM and two magazines.

“Don’t fret, I won’t leave a mess.”

Okay, the Makarov PM is a clue. Unless the assassin is using old surplus equipment, the story must be set sometime between the late ’40s and early ’90s. Now that he’s got his pistol, what does he do with it? Is there a holster? Does he slip it in his pocket? Surely he must load it (unless the two magazines Natalya hands him are extras). My point here is that once you introduce an object, yhou can’t just let it disappear from the page.

“You’re lucky, going to a tropical place,” she muttered wistfully.

“I wouldn’t exactly call it lucky.”

“But the weather’s better.”

“Yes, it is. Spasiba do svidaniya myshonok,” he muttered as he opened the door, checked the hallway, and slipped away.

Jim Bell blogged last Sunday on using dialect and foreign words in manuscripts. “Spasiba do . . .” translates in my head as blah, blah, blah. Also, where’s the emotion? They talk about the weather, and then Steele just walks away.

This section highlights a lack of point of view. Whose scene is this? I’d like to be in someone’s head, but instead, I’m just watching the players move around on the set. I’d like to feel something from someone.

Natalya pulled the mobile from the inside pocket of her jacket. “Did you get all of that?” she asked Pierce.

“Yes. But he lied, our Adrian did.”

What is the lie?

“You mean –?”

I’m lost. I don’t know what they’re talking about.

“Oh, he won’t miss his flight, he knows what’s on the line.”

“But he’s off the leash…”

“I let him do this, or he won’t do the job in Cuba. He’s the only one who can and he knows it. I’m not sure what he’s got planned, but it’s going to leave a hell of a mess.”

“Will he kill Voschenko?”

“He wants to. Thank you for your help Natalya. You should go to ground.”

“But…”

“Leave myshonok. Disappear. Now.”

I sense that here at the end, I’m supposed to be fearful, but I’m not. Dialogue can carry a scene only so far. As a reader, I don’t want to feel like I’m merely eavesdropping on someone’s conversation. I want to understand what’s going on. I want to understand the stakes.

What say you, TKZers? It’s your turn.