What Winnie the Pooh Taught Me About Writing

Terry Odell

First, on this Veterans Day, a thank you to all who have served.

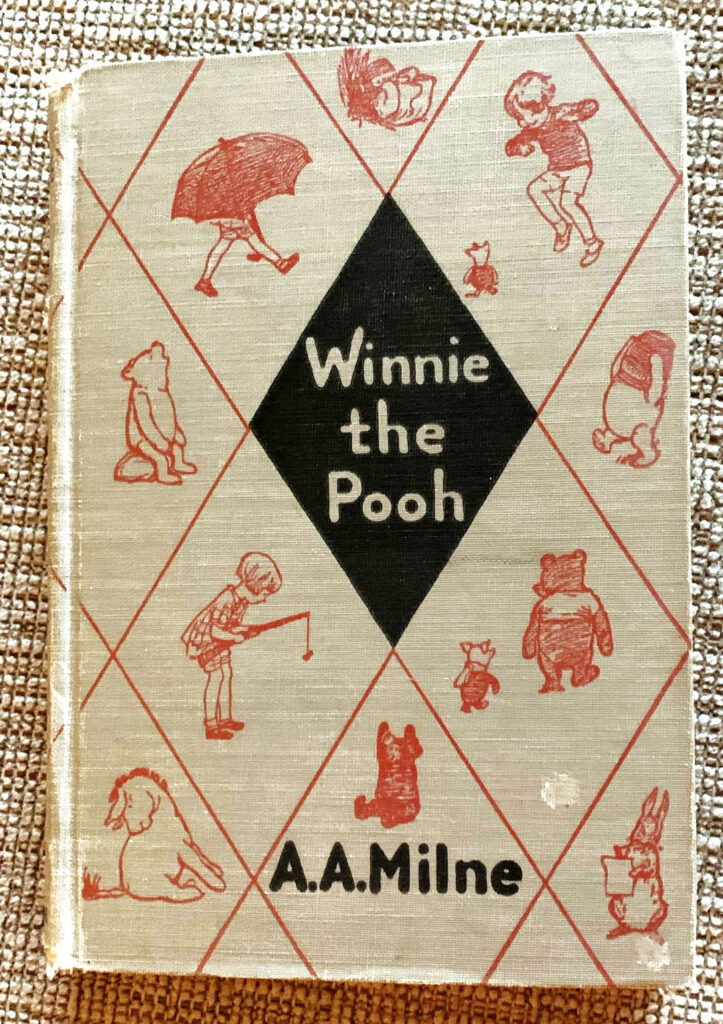

When I was a child, my dad would read Winnie the Pooh (the REAL one, not the Disney version) to me and my brother. I loved his voices (Years later, when an old movie was playing on the television, I heard Eeyore’s voice. I ran out to look and it was a W.C. Fields movie. I didn’t know my dad had been doing “real” voices when he read—but I digress.)

When I was a child, my dad would read Winnie the Pooh (the REAL one, not the Disney version) to me and my brother. I loved his voices (Years later, when an old movie was playing on the television, I heard Eeyore’s voice. I ran out to look and it was a W.C. Fields movie. I didn’t know my dad had been doing “real” voices when he read—but I digress.)

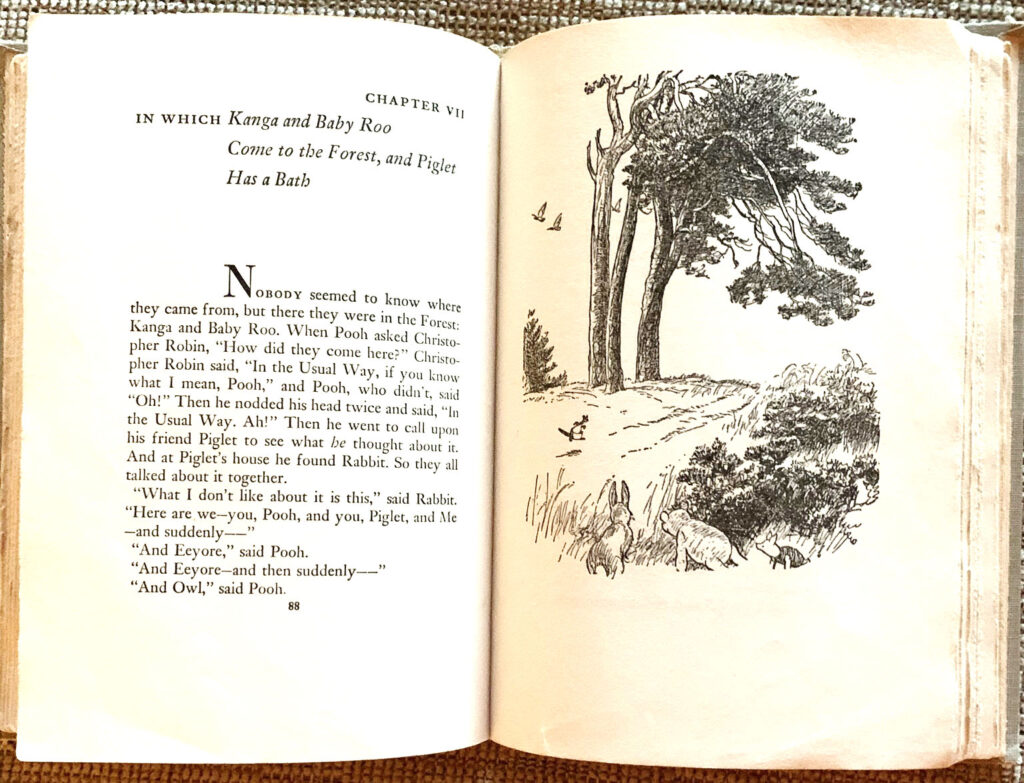

Another thing I remember from my dad’s reading was the way he began each chapter in a Very Important Voice. And the way each chapter was titled, “In Which…” followed by a few words telling us what the chapter was about.

(Kind of like “circles and arrows and a paragraph on the back of each one…” but I digress again.)

Although I certainly don’t title my chapters, the “In Which” approach helps make sure I’m putting something on the page that belongs there.

Too often, it’s easy to get carried away with description, or dumping in some back story, or including that “wonderful” scene that came to you when you overheard a conversation at the coffee shop, or salon, or when you were people watching and saw someone who just had to be in the book. So you write it, and it’s wonderful, and you’ve captured the moments perfectly. But is it moving the story. Is it something worthy of including in your “in which” summary of the scene.

Because you should be summarizing the scenes, either before or after you write them. And there need to be plot points (which is the official writerly term for “in which”). You’ll notice I used the plural. A scene had better be carrying more than one. While there’s no rule, and no exact number, I’d recommend shooting for three. Scene length, of course, can cause variations, but whatever happens in that scene needs to relate to the story.

Which brings me to kinds of scenes. Here’s a quick summary, gleaned from a RWA workshop, although most will carry over to any genre.

- Prologue – not required. In fact, unless there’s a huge time gap between this and the opening, it should probably be Chapter One. There’s also a difference of opinion as to whether agents want to see prologues when you’re submitting.

- Opening – should draw the reader in.

- Set-up — foreshadows something to come

- Validation – shows the character at work

- Conflict

- Push – moves characters apart

- Pull – moves characters closer together

- Reaction – also referred to as “sequel” (or shower scene, where the character would reflect on what just happened). These can slow the pace, so they’re falling out of favor. If you need one, make sure it’s important, and don’t linger too long.

- Flashback – use sparingly – they’re often found in reaction scenes

- Flash forward—rarely used in romance; author intrusion. Tends to be omniscient POV, which can intrude as well.

- Reversal/Black moment – everything goes wrong

- Climax – characters must make choices

- Conclusions – wrap up those dangling threads

- Epilogue – not required. Common in romance (although I’m not fond of them, personally)

Do you ever find scenes in books you’re reading, even very well-written scenes, that leave you wondering what they’re doing there? Have you found them while writing your own books?

My new Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is available at most e-book channels. and and in print from Amazon.

My new Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is available at most e-book channels. and and in print from Amazon.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Thanks so much for a great post, Terry. We can learn so much from the classics (there is a reason why certain books endure) and the basics (you had a parent (as I did) who read to you.

I appreciate your sharing that terrific summary. Re: Prologues…every time I encounter one that isn’t necessary I sigh inwardly. Sometimes outwardly.

To answer both of your questions: Oh, yeah.

Have a great day!

Thanks, Joe. The current WIP will need careful scene analysis when I hit ‘the end’ of the draft. It could use it now, but I have to see how it ends first.

Thanks for the memories. During my growing up years, my mother read Winnie the Pooh to me and my siblings. Recently, I looked for the old books and discovered a sibling had inherited the treasures. I bought the “Classic Collection” to read to my grandchildren. I need to get those books out and start reading again.

The answer to your question is “maybe.” I’ve been studying plotting with character-driven stories, and I’m still in the fog as to how to do it. I think I have a handle on plotting in plot-driven stories. Someone described the “spine” of the story and making certain each scene was an essential part of that spine.

Thanks for a great post.

Thanks, Steve. (Those images with this post are from the books I had as a child.) I’m a “Planster” and usually rely on the characters to get me through the story. After 20+ novels, I think (hope) the structure becomes organic. I have trouble holding an entire book in my head, but “is this scene advancing the plot?” usually works for me.

Ah, Winnie the Pooh! And since Scooby Doo is my all time favorite cartoon character, if anyone feels compelled to relate that to writing, I’d love to read it!

RE: Finding scenes that shouldn’t be there: I’m trying to think of examples. While I have certainly read a few scenes here & there where an author’s scene was a bit thin (not serving multi-purpose as you describe with the plot points) that’s not usually what throws me (temporarily or permanently) out of a story. For the most part, for fiction I’ve read, by the time it’s published, they’ve done a pretty good job of making their scenes count.

I’m first-drafting right now, seat-of-the-pants style (not my usual M.O.) & I can guarantee on revision I’m going to have to give a hearty “Ruh-roh!” like Scooby & cut scenes that won’t have good purpose in the final manuscript. But right now they’re a prop for me as I feel my way through the story.

I had a lot of practice with this when I finished the first draft of my first novel. I was having such a wonderful time writing it (and learning the craft–I knew NOTHING when I started), that it ended up at 141,000 words. I think it ended up around 90K when it was done.

You can always put cut scenes onto your website. I have a “cutting room floor” section on my website, although it’s frightfully out of date.

That is a great idea, Terry!

Great post. I recently finished a book “in which” (heehee) three scenes in a row had the same characters and virtually the same external conflict/outcome. I was disappointed because the two extra scenes didn’t move the story along.

p.s. I could have totally missed something, of course, so I’m definitely not naming the book in case it was just me.

I doubt it was just you, Priscilla.

Thanks, Terry! Pasted into my file, as I’m going to use your “learnin” on my current WIP. I always wondered how to summarize and evaluate each scene. I’ve read many takes on it from other authors, but this post clarified a few things.

Loved your illustrations! Alas, my parents didn’t read to us, but Mom was a fine example for me. She could be found during her leisure moments (and with four rambunctious kids and a full-time job, there weren’t many of those to be had) curled up with a book. She gave me my love of literature and a keen eye for a not-right sentence. 🙂

And may I add my Thanks for your service to our wonderful veterans and their families out there…you’re the best of the best. (That includes you, Dad!)

Glad it helped, Deb. When I used my tracking board, I used 3×3 sticky notes to summarize the main points in each scene. It made me cut to the chase. I’m using a spreadsheet now, and I do get a little carried away. I need to differentiate between plot points and scene summaries.

Great post, Terry. I’m in the minority but I love a good prologue if they author knows how to use it. A jump cut, for example, works well to drag the reader along to the payoff scene. They also fear for the protagonist, which is always a good thing in thrillers.

Sue, I think anything works if the author knows how to use it. I used a prologue in my first mystery, because it happened well in the past. Given nobody in the book knew the character in the prologue existed, that scene saved trying to figure out how to reveal information to the readers in flashbacks.

My dad didn’t read and do voices, but he told his own stories in the venacular of the South so that was even better. Bushytail Squirrel, the sneaky little guy, always defeated the bully Fox. As a most impressive aunt, I did both original stories and voices.

I call scenes that have nothing to do with the narrative flow bubble scenes. They don’t affect the narrative or the characters in any way. They just float along the river of cause and effect in the story and do nothing. I rarely notice them in published works, but they are rampant in my students’ works, and I have been known to delete one in my own work.

I use “The Rule of Three” to not only figure out what I want to do in each scene but to recognize a bubble scene. If a scene doesn’t contain at least one or two plot points (information or events which move the plot forward), and one or two character points (important character information) so I have at least three points total, it should be tossed, and whatever points included in that scene should be added to another scene.

Love the term bubble scenes! Thanks, as always, for sharing your good advice.

Oh, I just remembered several bubble scenes in a traditionally published book. The heroine shoots someone, not involved in the plot, when she’s backed into a corner. The scene happens then nothing. She doesn’t think about it, she’s not traumatized, and it has nothing to do with the plot or is mentioned again. This was the same heroine who nearly cheated on the hero then went on her way with no guilt or change. The Teflon character strikes again.

Another good point. If you injure a character to add tension, make sure he’s not miraculously healed in the next chapter. You have to show how he’s dealing with it. (Unless he’s on TV and shot in the shoulder, right John Gilstrap!)

Hi, Terry

Love this post! As Joe mentioned above, there’s a reason why classics are classics.

I’m not a fan of prologues, and avoid writing them. I’ve certainly read some very well written ones, but the problem is, they can detract from the first chapter–if they are especially riveting, you want to find out what happens next, but if the opening chapter massively downshifts, pacing wise, then the narrative drive slows and I have trouble as a reader maintaining interest.

So, it is incumbent upon writers IMHO who use prologues to make sure that the following first chapter grabs the readers attention. If you use a prologue, you’re essentially opening a novel twice, and need to make both openings compelling.

It’s interesting that a structure television shows increasingly employ is opening with a reversal scene later in the narrative, followed by jumping back in time (“twelve hours earlier” etc), having dangled that upcoming crisis before the viewer. A sort of anti-prologue set up, if you will 🙂

Thanks, Dale.

“It’s interesting that a structure television shows increasingly employ is opening with a reversal scene later in the narrative, followed by jumping back in time (“twelve hours earlier” etc), having dangled that upcoming crisis before the viewer. A sort of anti-prologue set up, if you will.”

And I will go on record right now and say I hate those. I know they’re all going to be lying on the bank floor after a shootout. Why watch the rest of the show?

Good stuff, Terry. I’m a fence-sitter when it comes to prologues. I’m with you that if an author knows what they’re doing, then there’s no problem – as long as it furthers the story. I’m doing a series right now and have developed a formula (sort-of) where I made a flow chart template in which I plug each chapter (scene) and make sure it has an opening /closing reason as well as a necessary place in the overall book. I also use a whiteboard which has more ink than whitespace as well as yellow sticky notes all over the place. To each their own… as long as it furthers the story 🙂

I have a spreadsheet for tracking and a foam core board for points I need to work into the story. My critique partners are quick to tell me when I have a scene that’s not pulling its weight. Chapter ending hooks usually get fixed in edits.