by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

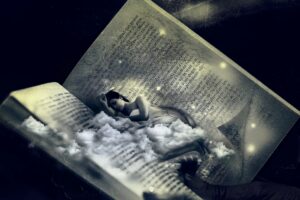

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumber’d here

While these visions did appear.

And this weak and idle theme,

No more yielding but a dream,

Gentles, do not reprehend:

if you pardon, we will mend.

– Puck, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Are you a dreamer?

By that I don’t mean someone who has a vision of how they’d like life to be, or of a goal they’d like to achieve. Those are good dreams to have. They keep us motivated.

I’m talking about when-you’re-asleep dreams.

I don’t dream a lot. But when I do, it’s choice.

And I have a distinct dream pattern.

Once a year or so I have a recurring nightmare. I’m on a cruise ship at night in the middle of the Pacific. Or maybe it’s the Atlantic. All I know is it’s the middle, and there’s no land or other ships in sight.

And I fall off the stern. (How is a mystery. Is it murder?)

Anyway, I splash into water, then pop my head up and see, leaving me at 30 knots, the lights of the cruise ship. I yell, but no one hears me.

As I tread water the ship gets further and further away, until it is only a dim light in the impossible distance.

That’s when I wake up.

What is this dream telling me? It’s not something mundane like fear of death, since I don’t fear it. But what else could it be saying?

Does it even have to say something?

Freud, of course, thought dreams were crucial windows into the psyche, revealing repressed impulses from childhood. He made a lot of cigar money that way.

On the other hand, Harvard psychiatrists J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley have proposed the Activation-Synthesis Model of Dreaming. This theory holds that the brain, when you’re asleep, tries to bring order to a chaos of neural activity we are completely unaware of. As Hobson puts it, “The brain is so inexorably bent upon the quest for meaning that it attributes and even creates meaning when there is little or none in the data it is asked to process.”

Who knows? I just know I don’t like my recurring nightmare and I’ll be happy if I never have it again.

There’s another pattern to my dreams. I like to get up early…I mean, really early, while it is still dark, the house is quiet, the coffee maker has my joe ready. In this tranquil time I’ll often write a little or read a little. I wait for my lovely wife to join me, and we usually have a little devotion together, or just talk.

Sometimes, depending on the amount of sleep I’ve had, I’ll head back to the sack for another hour or so of Zs.

This is when I often dream, and these dreams are vivid. According to Hobson, dreams tend to have five characteristics: illogical content, intense emotions, acceptance of the bizarre, strange sensory experiences, and difficulty remembering dream content upon waking.

But I usually remember these early morning dreams. The emotions are indeed intense, the narrative strange, and in my dreamscape I believe everything is absolutely real and happening.

Let me tell you about the most recent example.

My wife and I are in New York, staying at a hotel. We have a date to go golfing with Jerry Seinfeld. Seinfeld drives his car up and Cindy gets in. I tell them I’ve forgotten something and I’ll meet them at the golf course.

The dream cuts to me in a sleazy office in Midtown, renting a car. I get the car, which is in an alley, and drive to the end of it. I take out my phone to get GPS directions to the golf course. I’m having trouble with the connection, so I get out of the car and go to a newsstand which is right there to ask the guy for directions.

When I turn back the car is gone! Stolen! In five seconds flat!

I run down the street trying to spot it.

Nothing!

I’m saying, “Oh man oh man oh man!”

I run back to the car rental place, but it’s not there. I’ve apparently taken a wrong turn. I keep looking around in the building, but just run into closed doors, empty hallways, and finally the end of the corridor with a locked door.

And for some reason I have no shirt on.

Desperation choking me, I run out to the street, thinking I’ve got to call Cindy, now!

And I discover the shorts I was wearing for golf are gone. I’m now in a pair of new blue jeans.

With nothing in the pockets!

My phone is gone, my wallet is gone.

I run back into the building asking people if they’ve seen a pair of shorts anywhere.

Blank stares.

Now here’s the most intense part. In the dream I’m saying to myself, “Please let this a dream.” But I don’t wake up.

Oh no! This is real!

I run back to the street, losing breath, patting the jeans all over in a vain attempt to find my phone and wallet.

“Please, God,” I say, “let this be a dream!”

But no, I’m still there. It isn’t a dream at all. It’s happening!

And then I wake up.

For long moment I just lay there, catching my breath. Then realized it was a dream. Flooded with relief, I said out loud, “Thank you, God!”

I jumped out of bed and threw on my robe and looked for Cindy. She was at her computer, sipping her coffee. She was not golfing with Jerry Seinfeld.

Again, I have no idea what this dream signifies.

Do I want to meet Seinfeld?

Or was this just a bunch of neural activity with no meaning at all?

Perhaps we’ll never know for sure. But we don’t have to solve the mystery in order to use our dreams in our fiction. What I have done is the following:

- I’ve transferred intense emotions over to an emotional point in a scene.

- I’ve used one of my dream images as a metaphor in a scene.

- I will sometimes create a crazy dream for a character to have, but also observe my own rule: unless dreams are an intrinsic part of the plot, I use only one per book. I do so to expand reader identification with the emotions of the character. More than that is overdoing it.

Now over to you. Do you dream? Do you ever use your dreams, or parts of them, in your stories?