Please welcome Kate Raphael to TKZ as my guest today, continuing the discussion we started on diversity and cultural appropriation in fiction….

Please welcome Kate Raphael to TKZ as my guest today, continuing the discussion we started on diversity and cultural appropriation in fiction….

Where is the line between imagination and cultural appropriation?

Actors and musicians have faced that question for decades, but until recently, fiction writers seemed to have license to become, behind our pens, whoever we could convince readers we were. In the 1930s and 40s, Pearl Buck and James Michener won Pulitzer Prizes for their portrayals of Asian countries and the people who inhabited them. Tony Hillerman not only won several Edgars and a Nero, he received the Navajo Tribe’s Special Friends of the Dineh Award for his series starring Navajo policemen Jim Chee and Joe Leaphorn.

In the last few years, however, cultural activists and writers of color have begun to raise the issue of who has a right to tell their stories. This conversation is a natural outgrowth of the public feuds between Miley Cyrus and Nicki Minaj, or Iggy Azalea and Azalea Banks, but it has certainly been helped along by episodes like Kathryn Stockett’s alleged misuse of stories told to her by her brother’s maid, and Michael Derrik Hudson’s admission that he put the name “Yi-Fen Chou” on his poem because it was more likely to be accepted that way. (Pearl Buck, incidentally, was sometimes known by her Chinese name, Sai Zhenzhu.)

The realization that all fiction is appropriation was the breakthrough that let me start writing fiction in the first place. Until my mid-thirties, I thought I couldn’t write fiction because I had no imagination. Then one day something crazy happened to a friend of mine and I thought, “That would make a great movie,” so I started a screenplay. The script was awful, but I had popped the cork on my storytelling juice. One of my friends had been a draft resister and gone underground. Others survived illegal abortions or helped sandbag Black Panther offices. A friend of a friend was killed during the contra war in Nicaragua. Steal! My own lackluster life fell away and I had a plethora of exciting stories to tell.

But stealing from friends, people basically “like me” is a different animal than telling stories of people with less social power than I have, people who have often been denied the right to tell their own stories.

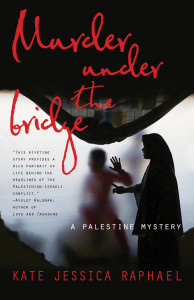

As I honed my debut mystery novel, Murder Under the Bridge, and its sequel, Murder Under the Fig Tree, set in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, I thought long and hard about whether it was fair for me, as a Jewish American, to write from the perspective of a Palestinian. The Palestinian people have fought long and hard for the right to control their narrative, a narrative which has been virtually eclipsed in mainstream U.S. media. Palestinian writer Susan Abulhawa, author of the novel Mornings In Jenin, suggests that efforts to speak in the voice of people whose oppression we do not share “colonise our wounds and bring our pain under their purview.” I think it’s a valid position, and I didn’t want to do that.

At the same time, to write about Palestine and NOT put Palestinians at the center of the story seems worse. If I could not write from a Palestinian perspective, I couldn’t write these books. I needed to write about Palestine because I am a writer who lived in Palestine for several years, and my life was changed by that experience. So I had no choice but to try to inhabit the persona of a Palestinian protagonist, and hope that I could do it justice. I took some comfort from remembering that almost every Palestinian who gave me food, shelter, Arabic lessons or a badly needed ride around the checkpoints asked only one thing in return: “Go home and tell people our stories.” I took this as tacit permission to create characters who could live those stories.

I also took heart from my memory of reading Laurie King’s first Kate Martinelli novel, A Grave Talent. Kate Martinelli is a lesbian, as am I. I could tell immediately that King is not. Martinelli’s partner asks if she’s a lesbian and she answers, “We don’t know each other well enough for me to answer that.” A lesbian would never say that; she might as well say yes, because no straight woman would say it – especially in 1993, when that book came out. There were other things that also didn’t ring true. Nonetheless, I liked the book pretty well, and I was confident that the character’s voice would get better in future books, which it did. I could tell that though King was stretching, her intentions were good, so I was willing to give her a chance.

My friend Steve Masover, author of the recently released novel Consequence, says that writing about anyone other than oneself requires “an act of radical empathy.” I nurture the hope that radical empathy will shine through the mistakes I have no doubt made in portraying my Palestinian protagonist, Rania. And if it doesn’t, I’m sure people will let me know.

Kate Raphael is the author of Murder Under The Bridge: A Palestine Mystery, and host of Women’s Magazine on KPFA Radio in Berkeley. Between 2002 and 2005, she spent eighteen months in Palestine as a member of the International Women’s Peace Service.