Please welcome Kate Raphael to TKZ as my guest today, continuing the discussion we started on diversity and cultural appropriation in fiction….

Please welcome Kate Raphael to TKZ as my guest today, continuing the discussion we started on diversity and cultural appropriation in fiction….

Where is the line between imagination and cultural appropriation?

Actors and musicians have faced that question for decades, but until recently, fiction writers seemed to have license to become, behind our pens, whoever we could convince readers we were. In the 1930s and 40s, Pearl Buck and James Michener won Pulitzer Prizes for their portrayals of Asian countries and the people who inhabited them. Tony Hillerman not only won several Edgars and a Nero, he received the Navajo Tribe’s Special Friends of the Dineh Award for his series starring Navajo policemen Jim Chee and Joe Leaphorn.

In the last few years, however, cultural activists and writers of color have begun to raise the issue of who has a right to tell their stories. This conversation is a natural outgrowth of the public feuds between Miley Cyrus and Nicki Minaj, or Iggy Azalea and Azalea Banks, but it has certainly been helped along by episodes like Kathryn Stockett’s alleged misuse of stories told to her by her brother’s maid, and Michael Derrik Hudson’s admission that he put the name “Yi-Fen Chou” on his poem because it was more likely to be accepted that way. (Pearl Buck, incidentally, was sometimes known by her Chinese name, Sai Zhenzhu.)

The realization that all fiction is appropriation was the breakthrough that let me start writing fiction in the first place. Until my mid-thirties, I thought I couldn’t write fiction because I had no imagination. Then one day something crazy happened to a friend of mine and I thought, “That would make a great movie,” so I started a screenplay. The script was awful, but I had popped the cork on my storytelling juice. One of my friends had been a draft resister and gone underground. Others survived illegal abortions or helped sandbag Black Panther offices. A friend of a friend was killed during the contra war in Nicaragua. Steal! My own lackluster life fell away and I had a plethora of exciting stories to tell.

But stealing from friends, people basically “like me” is a different animal than telling stories of people with less social power than I have, people who have often been denied the right to tell their own stories.

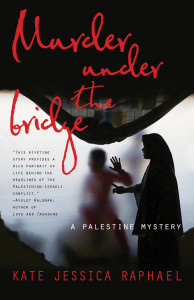

As I honed my debut mystery novel, Murder Under the Bridge, and its sequel, Murder Under the Fig Tree, set in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, I thought long and hard about whether it was fair for me, as a Jewish American, to write from the perspective of a Palestinian. The Palestinian people have fought long and hard for the right to control their narrative, a narrative which has been virtually eclipsed in mainstream U.S. media. Palestinian writer Susan Abulhawa, author of the novel Mornings In Jenin, suggests that efforts to speak in the voice of people whose oppression we do not share “colonise our wounds and bring our pain under their purview.” I think it’s a valid position, and I didn’t want to do that.

At the same time, to write about Palestine and NOT put Palestinians at the center of the story seems worse. If I could not write from a Palestinian perspective, I couldn’t write these books. I needed to write about Palestine because I am a writer who lived in Palestine for several years, and my life was changed by that experience. So I had no choice but to try to inhabit the persona of a Palestinian protagonist, and hope that I could do it justice. I took some comfort from remembering that almost every Palestinian who gave me food, shelter, Arabic lessons or a badly needed ride around the checkpoints asked only one thing in return: “Go home and tell people our stories.” I took this as tacit permission to create characters who could live those stories.

I also took heart from my memory of reading Laurie King’s first Kate Martinelli novel, A Grave Talent. Kate Martinelli is a lesbian, as am I. I could tell immediately that King is not. Martinelli’s partner asks if she’s a lesbian and she answers, “We don’t know each other well enough for me to answer that.” A lesbian would never say that; she might as well say yes, because no straight woman would say it – especially in 1993, when that book came out. There were other things that also didn’t ring true. Nonetheless, I liked the book pretty well, and I was confident that the character’s voice would get better in future books, which it did. I could tell that though King was stretching, her intentions were good, so I was willing to give her a chance.

My friend Steve Masover, author of the recently released novel Consequence, says that writing about anyone other than oneself requires “an act of radical empathy.” I nurture the hope that radical empathy will shine through the mistakes I have no doubt made in portraying my Palestinian protagonist, Rania. And if it doesn’t, I’m sure people will let me know.

Kate Raphael is the author of Murder Under The Bridge: A Palestine Mystery, and host of Women’s Magazine on KPFA Radio in Berkeley. Between 2002 and 2005, she spent eighteen months in Palestine as a member of the International Women’s Peace Service.

So, Killzone has decided to become overtly political?

Count me out. I do not believe in the ghettoization of storytelling. I’ll write my stories my way, about my characters, in the manner of my choosing.

I suggest the ninnies that whine about cultural appropriation do the same.

Wow! A complicated and sensitive issue, but carrying it to its extreme would mean that men couldn’t write from female POVs and vice versa, wouldn’t it? Eventually, all writers’ creativity would be stifled.

When we write from a POV that isn’t ours, we have an obligation to do the best we can to get that POV down in a way that is as authentic as possible. Many authors are able to accomplish this.

It requires research, empathy and compassion, and a solid understanding of human nature. It takes passion and honesty… and perhaps we need courage, too.

And let’s not forget knowledge of the craft.

But let us not self-censor, and definitely, let us not allow others to stifle our creativity.

Sheryl Dunn, that’s exactly where I ended up coming down. I used to think male fiction writers did not have a right to write about women, because their female characters never felt right to me. But then I never wanted to read their books because they don’t have any female characters. So ultimately, we have to take the leap, but we do have to think about it carefully. Just because I have the right to do something, doesn’t mean I SHOULD do it. I think Ellen Bravo has a great take on it in this piece, http://ellenbravo.com/writing-while-white/, where she talks about fiction writing requiring “audacity and humility.”

Good for you, Kate. It sounds like you were sensitive and caring to the people you were writing about. That’s commendable. Some might not care about their views and, dare I say, “just write.”

Very thought-provoking and a worthwhile topic of discussion which Kate handled in a very balanced way. I agree that we shouldn’t feel the need to censor our fiction and the perspectives we take. As a South African writer, I draw on the experiences of discrimination around me, even though I was not the one discriminated against, much as Kate drew from her interaction with people in Palestine. I think we need to go a step beyond merely discussing this and do all we can to give opportunities (training, publishing avenues, etc.) to those ‘voiceless’ who have a story to tell.

Thank you, Joan. I would love to hear more about your work and how you handled this issue.

As an Anglo-Chilean with a white English background, I am aware of this as I write my current novel. It’s main protagonist is a female Welsh detective investigating a case involving a Romani (Gypsy) girl. Lots of places that I can make cultural appropriation errors. But then I need to tell the story and stand up for the people that are misrepresented.

Or am I in danger of doing the same – misrepresenting them?

(P.S. I live in Wales.)

It’s interesting because my first reaction, after “Wow, a lot of identities there!” was that if you live in Wales, you are Welsh, right? But then I thought, no matter how long I lived in Palestine, I would never be Palestinian. (A friend of mine, from The Netherlands, has lived in a Palestinian village in the Jerusalem area for 30 years. She ran sort of an orphanage and raised dozens of kids, who all call her mom. But when she was telling me how to find her house, she said to ask for “The Foreigner’s House.”) So I guess that says something about how colonized the Welsh are, at least in my American mind, that I am not even conscious of the possible problems of an Anglo-Chilean writing from a Welsh perspective. I would love to know more about the issues it is raising for you.

Welcome Kate and for wading into a pretty tough arena and issue – I look forward to seeing our discussion today on TKZ.

Thank you, Clare, for giving me this chance to connect with other really smart and thoughtful writers! So happy to meet all of you.

Seems to me it’s in how you portray other ethnicities as you crawl into their skin. If you’re going to prejudge, debase an entire group based on religion or skin color you’re not capturing reality and you’re putting yourself between the story and the readers where your work will suffer from it and most likely have a very limited audience if one at all.

But in Kate’s example, she spent 18 months living with Palestinians and sees them as human beings who have a story that needs to be told. And if that story is told by an empathetic Jewish lesbian, so be it.

I think it’s a good idea to ask someone from a different ethnicity (or other group) to read over the manuscript and give his/her input about the way their group is portrayed.

This is actually something the panel at the recent SCBWI conference suggested would be helpful to do.

My great-great-grandfather was the last Sun Dance priest of my mother’s tribe. His son, my great-grandfather, was the first ordained Christian minister in my mother’s tribe.

My great-great-great grandmother was at the Sand Creek Massacre, though we’re not quite certain whether or not she was in one of the bands who were attacked. (Though we do think so.) After walking to the supposed safety of reservation life in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), she was in Black Kettle’s camp the morning it was attacked by Custer’s Seventh Cavalry. (May Custer and his men be now burning in hell.) Black Kettle and his wife were shot in the back as they tried to flee on horseback. An American flag–our beloved red, white, and blue–flew above his camp. He had been promised his band would be safe if they flew the American Flag.

On the other side of my family, my great-great uncle was the last Principal Chief of the Creek Tribe of Oklahoma. There is thought that he might have been the first governor of the State of Sequoyah, the name the Indian tribes had thought they would name their state, as promised by the federal government.

I have said these things to brag. No, I have said these things to qualify myself to point out that Ms Raphael confuses cultural sensitivity with political correctness.

Yes, it’s perfectly fine for people of one race, political, military, religious, or cultural affiliation to write about those of other races, religions, and so forth. And we can–we should–write without apology for doing so.

Calder Willingham did so when he wrote the script for Little Big Man. (That movie fictionalizes the attack of Damncuster upon my ancestor’s camp at the Washita River.) Was it an accurate portrayal of her people? No, of course not. Most Indian elders are not spooky old folks who see elephant spigots in the shop where a preacher’s wife–how else can I say it?–gets screwed in the basement? Willingham was having fun, poking insult and braggadocio at White People.

There are a couple of things I’d like to poke Willingham in the nose for. But not because he was writing satire that happened to include American Indian people. He also satirized White culture. The sanitization was fun for all of us. Except at one point: after the attack sequence was over, the theaters I saw the movie in were always deathly quiet. In one, a woman wept from the time Sunshine and her and Little Big Man’s baby were brutally murdered. (In another theater, as the audience was leaving the theater, one man asked his wife if she’d like to stop for pizza or something. “Oh, shut up, you @$#@& blankety-blank white man,” she replied. No one dared laugh.)

See? Writing of other cultures can be entertaining, fun, and poignant. Because Willingham was willing to take on the issues his satire raised with an honest look. (Although I did feel a little patronized sometime.) But he was willing to take on the issues, knowing he would offend people.

In other words, he was not sensitive to political correctness. He wrote to entertain, with some thought to bringing up issues.

Ironically, I am writing this on a day when a Palestinian woman drew a knife on an Israeli employee who was doing his required job. She made an honest effort to kill the employee. She was shot dead by Israeli police. Political correctness would require us to see the attack in a sympathetic light–that it’s always correct for Palestinian women to try to kill Israelis. Honesty and integrity would have us look with bravery at the same issue and portray it with the same kind of artistic honesty and integrity: sometimes, it’s not right for a Palestinian woman to try to kill an Israeli, and she might be shot for doing so.

Political correctness cannot possibly help us in a search for truth in artistry.

Post Scriptum (I say with pomposity): I use the designation American Indian rather than the politically correct Native American. Everyone born in the United States of America is a Native American.

While I appreciate your perspective, I need to point out a couple things:

— While I don’t think it’s right to try to stab random people, what happens when the job of the person who is “just doing his job” is to occupy someone else’s land? At what point is it legitimate to try to kill them?

— I don’t know that all Indians would agree with you about Willingham. The fact that he didn’t only stereotype Indians/Native Americans doesn’t mean some stereotypes don’t hurt more than others.

Thanks for taking the time to respond.

Pingback: Writing Down: Cultural Appropriation and the Fiction Writer’s Dilemma | Kate Jessica Raphael