by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I enjoy getting emails and tweets from writers regarding the “mirror moment,” which is the subject of my book, Write Your Novel From the Middle. Recently I received two that I thought would make good fodder for a post (we at TKZ are always looking for good fodder).

I enjoy getting emails and tweets from writers regarding the “mirror moment,” which is the subject of my book, Write Your Novel From the Middle. Recently I received two that I thought would make good fodder for a post (we at TKZ are always looking for good fodder).

The first email was a great question from someone who asked about the mirror moment in a long series. She used Sue Grafton’s alphabet series as an example. Should each book have a mirror moment? How can a series character go through so many changes?

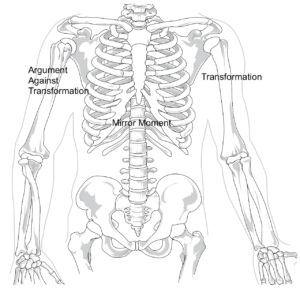

I wrote back reminding her that there are two kinds of mirror moments. The first kind is about identity. It asks questions like, “Who am I? Why am I this way? What must I become?” It’s Rick in Casablanca.

The second kind is about death. It is the realization, “I’m probably going to die. The opposition is too great. How can I possibly survive?” That’s Dr. Richard Kimble in The Fugitive.

So I suggested that in any Kinsey Millhone mystery (and in mystery series in general), there could always be a realization in the middle that this case, this puzzle, this villain is the most perplexing or dangerous of their career. It looks like they could “die” (professionally) this time.

But that is not to say the character in any given book in a series cannot have a personal crisis of identity, too. Exhibit A would be the Harry Bosch books by Michael Connelly.

C is for confession: I have not read all of the alphabet books by Sue Grafton. I think I may have stopped around F. But the question intrigued me, so I went to the library and picked one of the later books at random—Q is For Quarry. I sat down and, as is my practice when mirror hunting, turned to the physical center of the book and just started looking around. Was there anything relating to identity? Or anything indicating this was the biggest challenge of her career?

Lo and behold, I found that it was about identity. Kinsey, who lost both her parents in a car accident when she was very young, has had a hole in her identity ever since. In this scene from the middle of the book, she is looking at a photograph of her mother. You don’t even have to know the details of the plot to know that this is the language of an identity-type of mirror moment:

I placed the frame on my desk, sitting back in my swivel chair with my feet propped up. Several things occurred to me that I hadn’t thought of before. I was now twice my mother’s age the day the photograph was taken. Within four months of that date, my parents would be married, and by the time she was my age, she’d have a daughter three years old. By then my parents would have had only another two years to live. It occurred to me that if my mother had survived, she’d be seventy. I tried to imagine what it would be like to have a mother in my life—the phone calls, the visits and shopping trips, holiday rituals so alien to me. I’d been resistant to the Kinseys, feeling not only adamant but hostile to the idea of continued contact. Now I wondered why the offer of simple comfort felt like such a threat. Wasn’t it possible that I could establish a connection with my mother through her two surviving sisters? Surely, Maura and Susanna shared many of her traits—gestures and phrases, values and attitudes ingrained in them since birth. While my mother was gone, couldn’t I experience some small fragment of her love through my cousins and aunts? It didn’t seem too much to ask, although I still wasn’t clear what price I might be expected to pay.

I locked the office early, leaving the photo of my mother in the center of my desk. Driving home, I couldn’t resist touching on the issue, much in the same way the tongue seeks the socket from which a tooth has just been pulled. The compulsion resulted in the same shudder-producing blend of satisfaction and repugnance.

Thus, any book in a long-running series can include subplot elements that relate to the hero’s identity and transformation.

Shortly after this I got an email from my friend, writer Rich Bullock. He told me he’d been watching Star Wars: The Last Jedi, and in the chapter titled “The Mirror Cave” Rey is being tempted by the dark side (what a shock) and challenged by Kylo Ren on her true identity. Rich told me it was smack dab in the middle.

So I checked out the DVD from the library, chucked in the player, and went to the scene. Rey has fallen into this mirror cave, and is hoping it will give her a clue about who she truly is. Kylo Ren is somewhere else, but able to communicate with her:

KYLO REN: Let the past die. Kill it if you have to. That’s the only way to become what you were meant to be.

REY: No! No!

REY (VOICE OVER): I should have felt trapped or panicked. But I didn’t. This didn’t go on forever, I knew it was leading somewhere. And that, at the end, it would show me what I came to see.

REY: Let me see them. My parents … please.

She touches the mirror. Two shadowy figures approach from the other side of the glass. But when the frost clears, Rey is looking at … herself!

I took a look at the DVD timeline:

Hmm, we’re 1:16 into a 2:32 movie. I’m no math whiz, but I believe you can’t get any more middle than that!

The mirror moment works every time.

(For more on this, see my post “Revisiting the Mirror Moment”.)

That’s it for today, kids. I’m on the road most of the day, but will try to check in later. Talk amongst yourselves, esp. those of you writing series characters. How do you handle any inner transformation?