@jamesscottbell

When I began studying writing in earnest it was with an eye to becoming a screenwriter. This was back in the day of the “screenwriting guru” explosion. Syd Field was the granddaddy. His Screenplay was my foundational book and led to my eventual breakthrough on structure. Soon, Robert McKee came on the scene, then John Truby and a few others. Acolytes of each would claim that their guy was the true originator of screenwriting knowledge for the unwashed mass of wannabes.

Only none of them were. The original guru was a veteran Hollywood screen and TV writer who started teaching for UCLA Extension in the 1950s. His book, Writing the Script, came out in 1980. Wells Root was his name and you can look up his credits on IMDB.

Wells Root directing Donna Reed in Mokey (1942)

The other day I turned on TCM and decided to watch a little of the upcoming flick, a B gangster picture from the 30s called Public Hero #1. I saw that it had Chester Morris in it, and I like his work. The credits rolled and lo and behold Wells Root was the screenwriter. Now I watched with added interest, and ended up taking in the whole thing. The plot moved, had twists and turns and original characters. A crisp 89 minutes. Nicely done, Wells!

So I went to my bookshelf and pulled down Writing the Script for a re-read.

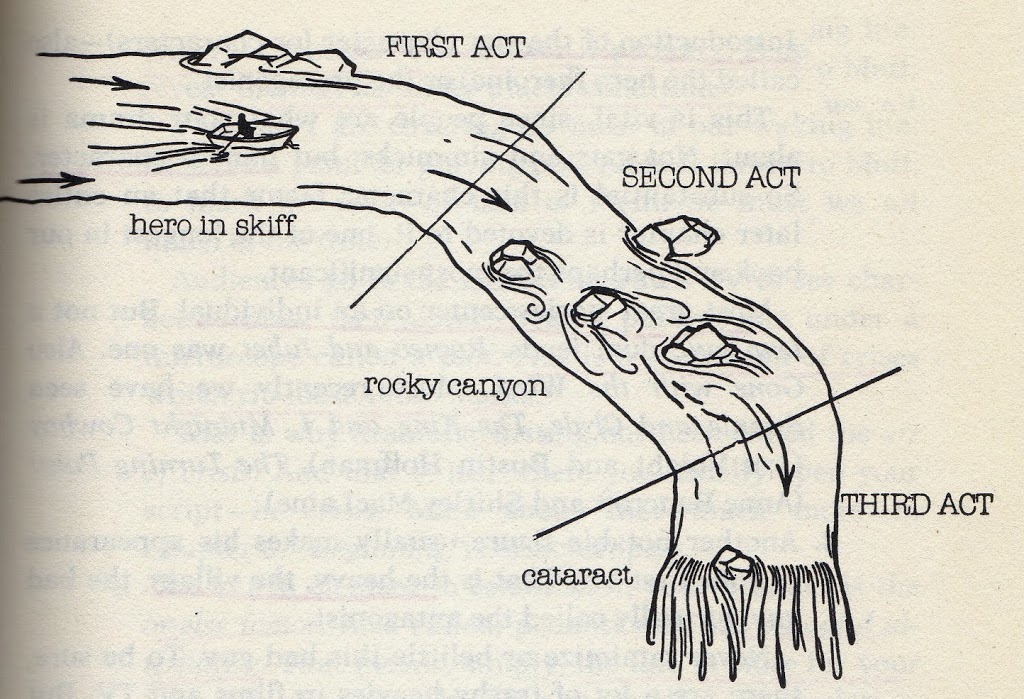

It’s nice to make its acquaintance again. Writing the Script is filled with gems of wisdom for both fiction and screen writers. And Root’s illustration of the three-act structure (as a raging river) is brilliant. He came up with this metaphor years before Syd Field’s famous three-act “paradigm.”

You see how the hero is in the river of story, being pulled by the current despite his best efforts with the oars. He gets thrust into the hazardous, rock-infested white water of Act 2. He fights all that only to hit a waterfall in Act 3. As he goes over the audience is asking, Will he drown or somehow make it to safe water?

I’ve always thought the best writing education would have been to be a young writer in Hollywood in the 30s. Then you could have hung out at Musso & Frank, listening to old scribes like Ben Hecht and Wells Root and John Howard Lawson. Over Martinis they would have provided a graduate course in the finer points of dramatic writing.

Since that era is long gone, Root’s book will have to do. So pull up a chair and listen to some of his advice:

Ultramodern, unstructured story design has an erratic record bringing bodies to the barn.

Drama favors the great saint or the great sinner—heroes and rascals who are above the common run. But they must still be as welcome in the village pub as in the manor house.

If you have the guts to be totally honest, nobody can write a character exactly as you can.

An unmistakable mark of a master craftsman is that he individualizes all his characters. (In the margin of the book I had scribbled “Moonstruck.”)

Although your heavy is a horror, make him or her also a vulnerable human being.

Write a man or woman or child who is everybody, but who becomes in your dramatic story an absorbing variation, a striking original.

The heights of emotional drama dwell in these scenes that plead truth from opposed points of view. Such conflicts, you will find, play with a special luminous power.

A story maker’s urgent priority should be awareness. A writer is always in his working clothes.

Agents and producers are flooded with the commonplace. Routine work will get you nothing but routine indifference.

So there it is, an afternoon hanging out with Wells Root, the first of the great screenwriting gurus.

Is there a “wise old scribe” in your background? Somebody from whom you got much needed advice? Tell us about it. [NOTE: I’ll be in travel mode today, so talk amongst yourselves and I’ll try to catch up later]