James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

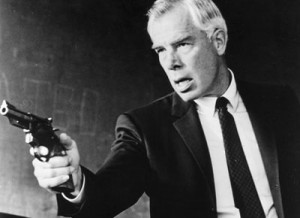

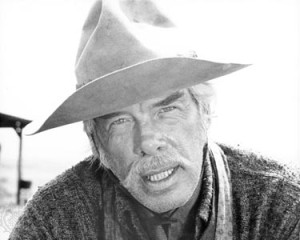

We had some great comments on my post about Lee Marvin and writing your truth. I just finished watching Cat Ballou again, and I have to say Marvin’s Best Actor Oscar was well deserved. Remember, he wasn’t up against some powder puffs. His competition that year was Richard Burton, Laurence Olivier, Rod Steiger and Oskar Werner.

But Marvin deserved the gold statuette because, as the old actor Edmund Kean said on his deathbed: “Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.”

Marvin’s portrayal of the drunken gunfighter Kid Shelleen required just the right touch, and boy did he have it. Then I watched The Killers, a 1964 crime pic with Marvin playing a hit man (targeting one Ronald Reagan in his last movie role). In what could have been a standard-issue performance, Marvin put unique spin on the role and gave another great performance.

Whatever you write, you must put your particular stamp on it. Do that, and you can write great stories.

I mean it. Your category romance can be great for its genre. Or your police procedural. Or your vampire novel. Anything. But it requires more than giving us what we’ve seen before.

Stamp is another word for voice. It’s that indefinable something that readers (unconsciously) and agents/editors (consciously) look for in a writer.

Stamp is another word for voice. It’s that indefinable something that readers (unconsciously) and agents/editors (consciously) look for in a writer.

How do you find it? Let me suggest the following (with apologies to Sue Grafton):

S is for Self – Look within before you start writing anything. Have an emotional connection to the material. Your own wiring creates the hum in your voice. Don’t ever write only to “sell.” Readers can sense that a mile away.

T is for Training – It takes skill to put yourself on the page in a way that communicates. That’s why I call structure “translation software for your imagination.” Without it, you frustrate rather than capture readers. Craft comes from practice and study. Produce the words! But also have a systematic program set up for yourself to keep learning how to make your words more effective.

A is for Audacity – Don’t be afraid of pushing yourself. Take risks in your writing. Go where the fear (or at least, the uncertainty) is. See what happens in the dark corners. Make life unbearably hard on your characters. You can always revise later, but playing it safe up front leaves potential gold in the ground.

M is for Moments – Great fiction is about great moments. Clarice Starling’s first encounter with Hannibal Lecter. Katniss Everdeen singing a lullaby to the dying Rue. That carriage ride in Madame Bovary. Get to the big moments in your story and overwritethem. Don’t hold anything back emotionally. When you revise, that’s when you shape the moment by trimming or nuancing.

P is for Passion – Care about what your story is really about. You might not be able to sense it at first, but it’s there (we call this theme or premise). Look deep into your characters’ motives and yearnings. Including the bad guys. Justify everyone’s position as they fight it out. The emotional cross-currents you create will enchant your readers.

Which brings me to my new release: FORCE OF HABIT 2: AND THEN THERE WERE NUNS.

This is the second novelette in my series. What is my stamp on this? Why am I writing about a nun who kicks butt?

For me, it started with the concept, which delighted my writing Self. Delight is a good thing to have when you write. Especially when your aim is entertainment.

Training: A novelette is short form (about 15k words) and I’ve been studying that form as the e-book revolution has taken off. All writers now should be producing short form work in addition to full length novels.

It was Audacious. Risk was involved. I did not know enough about nuns when I started. But I found a couple of experts (i.e., nuns who were willing to talk to me) for research. I wanted to be respectful and not devolve into a cartoon. And writing from the POV of a thirty-year-old former child star who went into the devoted life was a cool challenge.

The Moments I wanted to write were, first, the fight scenes. Also, there’s a wonderful moment in FORCE 2 that came out of the blue for me, so I just wrote it to see what would happen. Then beta readers told me they loved it. Thus, the wonderful alchemy of “the boys in the basement” worked again. (Hint: a celebrity is involved).

And Passion. I’ve always been interested in things philosophical and theological—the big questions of life. And in these stories I stumbled upon an issue: the use of violence to stop evil. Talk about something that is on a lot of minds these days! In the Catholic tradition there is a long-standing debate over the “just war.” Well, I brought that down to the personal: what if a nun could stop someone from doing evil by laying them out cold? And found out she was good at it? Indeed, what if part of her enjoyed it, while the other part wondered if she was entirely normal?

Training: A novelette is short form (about 15k words) and I’ve been studying that form as the e-book revolution has taken off. All writers now should be producing short form work in addition to full length novels.

It was Audacious. Risk was involved. I did not know enough about nuns when I started. But I found a couple of experts (i.e., nuns who were willing to talk to me) for research. I wanted to be respectful and not devolve into a cartoon. And writing from the POV of a thirty-year-old former child star who went into the devoted life was a cool challenge.

The Moments I wanted to write were, first, the fight scenes. Also, there’s a wonderful moment in FORCE 2 that came out of the blue for me, so I just wrote it to see what would happen. Then beta readers told me they loved it. Thus, the wonderful alchemy of “the boys in the basement” worked again. (Hint: a celebrity is involved).

And Passion. I’ve always been interested in things philosophical and theological—the big questions of life. And in these stories I stumbled upon an issue: the use of violence to stop evil. Talk about something that is on a lot of minds these days! In the Catholic tradition there is a long-standing debate over the “just war.” Well, I brought that down to the personal: what if a nun could stop someone from doing evil by laying them out cold? And found out she was good at it? Indeed, what if part of her enjoyed it, while the other part wondered if she was entirely normal?

So that’s my stamp. When I write anything, from the fun of FORCE OF HABIT to the suspense of DON’T LEAVE ME, I try to make this connection to the material.

So what about you? What does your writing stamp look like? Do you think about it before you write? Or do you find it as you go along?

And: are you taking enough risks?

And: are you taking enough risks?

***

FORCE OF HABIT and FORCE OF HABIT 2 are both priced at 99¢. Enjoy!

FORCE OF HABIT Kindle

FORCE OF HABIT Nook

FORCE OF HABIT 2: AND THEN THERE WERE NUNS Kindle

FORCE OF HABIT 2: AND THEN THERE WERE NUNS Nook