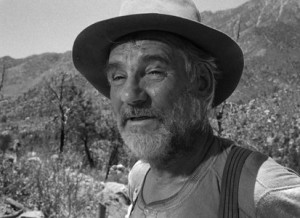

Here is another entry from the unpublished journal of that great pulp writer, William “Wild Bill” Armbrewster. The first entry can be found here. The second is here.

I was killing a dame when Benny walked in.

The dame was Gilda Hathaway and she was an icy blonde in the story I was pounding out for Black Mask. The killer was her husband, an action Jackson named Mickey Hathaway. He was about to use an ice pick on his wife when Benny said, “Hello, Mr. Armbrewster.”

“What? Huh?” I looked up from my Underwood, which was sitting on my usual table at Musso’s in Hollywood. “Don’t you know better than to interrupt a writer when he’s typing?”

“I’m sorry, sir, I thought we had—”

“I don’t care what we had! Go get yourself a Coke and let me finish my murder!”

Benny put his head down, but he did what I told him. I liked that about the kid.

Mickey dispatched Gilda, then wiped his fingerprints off the ice pick. He was out of the apartment by the time Benny got back to the table.

“Say, kid,” I said, “you’ve got the hangdog look of a mortician without a stiff. What gives?”

“I do have a stiff,” Benny said. “It’s that story you told me to write. I just couldn’t. I don’t know, I froze. I just sat there staring at the paper.”

“Welcome to the world of the professional writer, son.”

“This is what it’s like?”

“A blank page is God’s way of telling us how hard it is to be God.”

He stared at me like I was the blank page.

“Before you try to write anything,” I said, “you’ve got to get your head right. You’ve got to get your mind running like Seabiscuit at Pimlico.”

Benny took a sip of his Coke, looking more concerned than ever.

I took out a White Owl, bit off the end, fired it up. A matronly woman at the adjoining table gave me a hard look. I made a mental note to put her in my story as another victim of the ice pick killer.

“You’ve got a will to fail,” I said.

“I do not!” Benny said. Good. He had a fighting spirit. He was going to need that if he wanted to make it in this game.

“Cool your radiator, Benny. We all have a will to fail. It’s subconscious. It’s deep in the memory banks. All of the things we tried to do in our past, and failed at, collect there. All the embarrassments we’ve suffered, all the people who made fun of us, those experiences pepper our brains. It’s human nature. We almost always act in order to avoid pain. So rather than try something and possibly fail, we freeze up. Or we choose something easy because we know there’s no risk of failure. We don’t act boldly.”

Benny was silent, but I could tell I was getting through.

“Our job is to fight that will to fail, to give it the boot. You were afraid I’d rip apart your story, so you didn’t write it.”

Benny paused, frowned, then said, “You’re right.”

“Of course I’m right. This is Armbrewster you’re talking to.”

“So what do I do?”

“You really want to know?”

“More than anything!”

“More than a new Packard?”

“Yes!”

“More than a sweet gal to smother you with kisses?”

“I kind of want that,” he said. “But only after I’m a successful writer!”

“Just what I wanted to hear, kid. So here’s what you must do from now on––write as if it were impossible to fail.”

“That’s it?”

“It? Why, boy, I’m giving you the Promethean fire here! If the gods find out I’ve told you, I could get lashed to a rock and have my liver pecked out by a predatory bird! Which, by the way, isn’t all that different from working with an editor.”

“But I can’t just write that way, can I?”

“You’re not a Presbyterian, are you?”

“Methodist.”

“Then you’re a free-will being! And as such you are in control of your thoughts. And if you don’t control them, they will certainly control you. It takes effort, sure, but so does anything worthwhile. Now, have you ever done anything successfully?”

“Sure.”

“Like what?”

“I ran the anchor leg on our state championship relay team in high school.”

“Aces! Think about that moment.”

“Now?”

“No, in the late Spring of 1954. Of course now! Close your eyes and keep ’em closed.”

He did as I asked.

“You remember taking the baton?” I said.

“I sure do.”

“Remember your adrenal glands firing on all cylinders?”

“Uh-huh.”

“How about the roar of the crowd, the feel of the track, the exhilaration of crossing the finish line?”

“Yes!”

“Drink it in!”

“I’m drinking!”

“Keep those eyes closed. Your teammates are around you, slapping you on the back.”

“Yes.”

“And your best girl is in the stands, watching.”

“Judy Parrish! How did you know?”

“This is Armbrewster. Now, you’re feeling good, right?”

“Yes.”

“You see? You’re in control of your thoughts and your thoughts feed your feelings. Now, I want you to see yourself standing in Stanley Rose’s bookstore, holding your novel from Scribner’s in your hands, as a crowd starts to gather for your reading.”

Behind those closed lids, Benny’s brain was starting to run. When he smiled, I knew he was ready.

“Open your eyes! Next time you freeze up, remember those good feelings and imagine yourself with the book. Then write as if it were impossible to fail.”

“Does it really work?”

“A sweet kid named Dorothea Brande wrote a book called Wake Up And Live! and it sold a million copies. It’s the only way to stomp that will to fail and write your best stuff.”

“Swell! Now get back to your room and start typing.”

Springing up, he almost knocked over the table. He did a 50-yard dash out the door.

I sat back, remembering when I felt the way Benny did right now––ready to write like the wind. To write as if I couldn’t fail. That got me through a lot of cold nights and dismal days. And now here I was, making a living with the written word, but also realizing I’d been skating on the story I was working on. The encounter with Benny left me with the uneasy feeling I was playing it safe, mailing it in, avoiding risks. That old will to fail can sneak up on you like a jungle viper.

“Phooey!” I said.

I tore out the page I’d just typed, crumpled it, tossed it on the small pile at my feet. Then rolled in a fresh piece of paper.

This time, Gilda had an ice pick of her own.

Do you have fear when you write? Do you find yourself afraid to take risks?

Do you have fear when you write? Do you find yourself afraid to take risks?