By PJ Parrish

Just back from my duties as banquet chair for the Edgar awards. It’s the first time in three years that the event, sponsored by the Mystery Writers of America, has been held live. Three years…

Seems like longer. The Edgars have been a virtual event and it was great seeing men in tuxes and women in heels again. Great seeing old friends. Even greater meeting new ones. I’ve been chairing this event (spearheaded by MWA executive director Margery Flax) for more than a decade now. And it feels like the torch is being passed to a new generation of crime writers. Our theme this year was “Top of the World” (hat tip to Tom Petty for that inspiration). Because top of the world is how you feel when you’re an Edgar nominee. One of my favorite duties of the night is manning the nominee registration table. Man, I wish I could bottle the fizzy-feeling emanating from the writers as they collected their red-ribbon badges and drifted off in a daze to the cocktail reception. Great books this year, but alas, only one book in each category wins at evening’s end.

Just for fun, I’ve read the first pages or so of all the novel nominees. You can easily do the same — click here for complete list. But I thought it would be maybe instructive to take a look at how the winners opened their stories. Ahem…I will not be red-penciling their First Pagers. But feel free to weight in with your comments.

Best Juvenile: Concealed

“Your name?” The barista asked, holding the paper cup in the air.

I hesitated. For a moment I couldn’t remember if my name was spelled with one n or two. Not that it mattered much, since by tomorrow I’d have to pick a new one.

“Joanna with two n’s,” I replied.

He nodded, scribbled something on the cup, and passed it down the line to a girl who began preparing the order.

My drink wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. A tall vanilla bean frappé with two pumps of cinnamon syrup, hold the whipped cream. Nothing too easy or too complicated. Something quickly forgotten.

Sort of like me.

Didn’t matter if my hair was dyed blond, red, or even its current shade of brown, I always played the part of some random homeschooled girl from nowhere in particular who usually kept to herself. I was a mix of people you might know, but could never really remember.

That had been the story for when I was called Ana, Beatriz, Carla, Diana, Emma, Faith, Gina, Holly, and Ivette. Joanna was no different. And tomorrow it would continue, except

this time with a name that began with the letter K.

Over the past few years it had all become a game for me. Picking a name while going through the alphabet gave me a sense of order and predictability in my highly unpredictable life. Dad had come up with the idea back when he was still the one choosing my names, but I’d decided to continue the pattern. The question was which K name to choose. It could last me either a couple of weeks, like Joanna, or almost a

year, like when I was Carla.

I never knew.

It all depended on when my parents said it was time to move on and start over.

______________

Me here: I love this concept: A kid whose parents are on the lam so she has to cope with not just the usual angst of pre-teen identity, but the reality of not knowing who she is at any given time. The voice is assured yet vulnerable and very believable. I bonded with this girl at the get-go. I also liked the mix of short and long paragraphs. I don’t read juvie, but I’d definitely read on here.

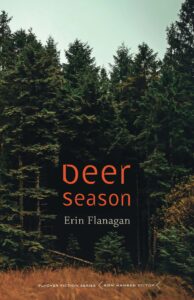

Best First Novel: Deer Season

Alma held the four-week-old pig against her left hip and pinned him to her side with an elbow. With her right hand she held his ear across his eye as Clyle positioned the syringe perpendicular to the flesh and injected the antibiotics into the piglet’s neck. The pig squealed and Alma’s grip wobbled as Clyle caught the pig by his two back legs, swooped him into the air, and streaked his back with a green Paintstik. On the ground the pig scuttered his hooves against the cement before gaining traction and taking off across the small pen to the rest of the litter.

This wasn’t how Alma wanted to spend a Saturday afternoon. This wasn’t how anyone wanted to spend a Saturday afternoon, but Hal had left Friday with some yahoos to go hunting the first weekend of deer season. She secured another pig across her knee as Clyle gave the shot, marked the piglet with the Paintstik, then moved her to the floor. There were two left unmarked, congregated by the far slatted wall. Clyle grabbed the plywood panel he used to divert the pigs, moving it right to left until one of the piglets was trapped, then reached down and picked him up by the back legs.

_____________

Me again. This is a very leisurely opening. The first chapter is devoted to Alma and her husband marking the piglets and it ends on a note of tension within the marriage. The novel has won raves, including a starred PW review, for its portrait of a small town both severed and knitted together by the tragedy of a missing girl. A little slow for my taste, but I would keep going.

Best Paperback Original: Bobby March Will Live Forever.

It’s Billy the desk sergeant that takes the call. A woman on the phone, breathless, scared, half-crying. She says, “I’d like to report a missing child.”

And suddenly, everything changes.

When news of a call like that comes in, everyone sits up at their desks, stops filling in their pools coupon, puts down their half-eaten rolls. The ones with kids open their wallets under their desks, look at the pictures of Colin or Anne or wee Jane and thank God that it’s not theirs that have gone. The young ones look very serious, try not to imagine pulling some weeping toddler from a cellar or frome under a bed, being congratulated by the boss, thanked by a tearful mother.

Those that are religious cross themselves or say a silent prayer to keep the kid safe. And those that have lived through a case like this before say hello to the familiar dread and fear in their stomach, the knowledge that there is no end to the bad things that men can do to children, that the missing child might be better off dead already.

And like a pebble dropped in water, the ripples start to spread throughout the city. No matter the lockdown, news of a missing child always gets out. Cops come home, tell their wives and girlfriends not to tell anyone but they do. A shilling drops in a phone box across the road from the station, a reporter at the Daily Record answers, and a beat cop earns a tenner for his trouble. Isn’t long before the boys selling the papers outside Central Station are shouting, “Final edition! Missing girl!”

And as night falls and the chatter dies down there’s still one person who doesn’t know what Glasgow is talking about. Alice Kelly. All she knows is she’s got a cloth bag over her head, that her hands are tied and she’s wet her pants. It doesn’t matter how hard she cries for her mum, her mum can’t hear her. Nobody can.

____________

Me again. I really like this opening. It’s omniscient but feels intimate. Nice trick, that. I was drawn in by the rhythm of the writing itself. Note how the writer repeats the triad construction with simple commas. This, this, and then that. This, this, and then that. From the first sentence, we know we have a missing child yet the rhythm induces an almost lulling affect, mimicking the routine of cops coping and doing their jobs. It’s tragic…and normal. How awful. After a double break, the story then moves into the protagonist’s point of view. Well done, I say.

Best Novel: Five Decembers

Joe McGrady was looking at a whiskey. It was so new the ice hadn’t begun to melt, even in this heat. A cacophony surrounded him. Sailors were ordering beers ten at a go, reaching past each other to light the girls’ cigarettes. Someone dropped a nickel in the Wurlitzer, and then there was Jimmy Dorsey and his orchestra. The men compensated for the new noise. They raised their voices. They were shouting at the girls now, and they outnumbered them. The night was just getting started, and so far they weren’t drinking anything harder than beer. They wouldn’t get to fistfights for another few hours. By the time they did, it would be some other cop’s problem. So he picked up his drink, and sniffed it. Forty-five cents per liquid ounce. Worth every penny, even if a three-finger pour took more than an hour to earn.

Before he had a taste of it, the barman was back. Shaved head, swollen eyes. Straight razor scars on both his cheeks. A face that made you want to hurry up and drink. But McGrady set his glass down.

“Joe,” Tip said.

“Yeah.”

“Telephone—Captain Beamer, I guess. You can take it upstairs.”

He knew the way. So he grabbed the drink again, and knocked it back. The whole thing, one gulp. Smooth and smoky. He might as well have it. If Beamer was calling him now, then he was going to be pulling overtime. Which meant tomorrow—Thursday—was going to be a bust. Molly was going to be disappointed. On the other hand, he’d be drawing extra pay. So he could afford to make it up to her later. He put three half-dollars on the bar, wiped his mouth on his shirtsleeve, and went upstairs.

______________

I’m back. The era is the Pacific theater of WWII and the golden-age-of-noir style reflects this. The book got raves pre-Edgar, starred PW review, New York Times Best Mystery and glowing blurbs from Lehane, King, Child. The chapter ends with McGrady’s boss saying he’s been working for five years, this is his first murder, don’t blow it. Given the writing, I’d give it more time to get to a full boil. From all I’ve read, there’s a big payoff. Side note: The book was rejected by 25 publishers before being picked up by Hard Case Crime.

Young Adult: The Firekeeper’s Daughter

I start my day before sunrise, throwing on running clothes and laying a pinch of semaa at the eastern base of a tree, where sunlight will touch the tobacco first. Prayers begin with offering semaa and sharing my Spirit name, clan, and where I am from. I always add an extra name to make sure Creator knows who I am. A name that connects me to my father—because I began as a secret, and then a scandal.

I give thanks to Creator and ask for zoongidewin, because I’ll need courage for what I have to do after my five-mile run. I’ve put it off for a week.

The sky lightens as I stretch in the driveway. My brother complains about my lengthy warm-up routine whenever he runs with me. I keep telling Levi that my longer, bigger, and therefore vastly superior muscles require more intensive preparation for peak performance. The real reason, which he would think is dorky, is that I recite the correct anatomical name for each muscle as I stretch. Not just the superficial muscles, but the deep ones too. I want an edge over the other college freshmen in my Human Anatomy class this fall.

By the time I finish my warm-up and anatomy review, the sun peeks through the trees. One ray of light shines on my semaa offering. Niishin! It is good.

My first mile is always hardest. Part of me still wants to be in bed with my cat, Herri, whose purrs are the opposite of an alarm clock. But if I power through, my breathing will find its rhythm, accompanied by the swish of my heavy ponytail. My legs and arms will operate on autopilot. That’s when my mind will wander into the zone, where I’m part of this world but also somewhere else, and the miles pass in a semi-alert haze.

My route takes me through campus. The prettiest view in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, is on the other side. I blow a kiss as I run past Lake State’s newest dorm, Fontaine Hall, named after my grandfather on my mother’s side. My grandmother Mary—I call her GrandMary—insisted I wear a dress to the dedication ceremony last summer. I was tempted to scowl in the photos but knew my defiance would hurt Mom more than it would tick off GrandMary.

I cut through the parking lot behind the student union toward the north end of campus. The bluff showcases a gorgeous panoramic view of the St. Marys River, the International Bridge into Canada, and the city of Sault Sainte Marie, Ontario. Nestled in the bend of the river east of town is my favorite place in the universe: Sugar Island.

The rising sun hides behind a low, dark cloud at the horizon beyond the island. I halt in place, awestruck. Shafts of light fan out from the cloud, as if Sugar Island is the source of the sun’s rays. A cool breeze ruffles my T-shirt, giving me goose bumps in mid-August.

“Ziisabaaka Minising.” I whisper in Anishinaabemowin the name for the island, which my father taught me when I was little. It sounds like a prayer. My father’s family, the Firekeeper side, is as much a part of Sugar Island as its spring-fed streams and sugar maple trees.

When the cloud moves on and the sun reclaims her rays, a gust of wind propels me forward. Back to my run and to the task ahead.

______________

Me once more. I let this one run long because it is yet another slow-build opening, yet I felt connected to the character and interested in the what’s-to-come. The writer is dropping in character backstory early, but notice that she is savvy enough to also tease us. The first graph, for example, feels slow but then we get that last line: “A name that connects me to my father—because I began as a secret, and then a scandal.” And the narrator hints several times that there is a “task” ahead of her. I don’t read much YA, but this feels fresh and engaging to me.

Okay, I’m done. If you are struggling with your openings, I’d encourage you to go to that list of nominees and read the samples online. So much variety there! I think our genre is in good hands.

“If you write properly, you shouldn’t have to punctuate.” — Cormac McCarthy.

“If you write properly, you shouldn’t have to punctuate.” — Cormac McCarthy.