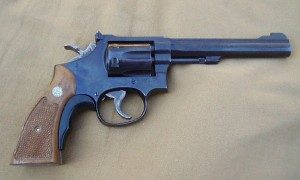

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000039_00007]](https://killzoneblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/CHILDHOOD_3_full-202x300.jpg)

E-book is 99 cents today!

By Jodie Renner, Editor, Author, and TKZ Emeritus

Have you thought about using your skills to help the less fortunate? Here’s a project I decided to try, and an easy way that you can help, too, if you’re interested.

I’ve been a freelance editor since 2007, when I retired early from a career as middle-school teacher and school librarian. Over the nine years since, I’ve continually increased my editing skills, and about a year and a half ago, I started thinking about how I could use those skills to give back, to help victimized people in the world, especially children.

I was doing a Google search when I came across the true story of a young Pakistani slave worker who was murdered for daring to protest against the inhumane conditions of Asian child laborers.

In 1986, when Iqbal Masih was four years old, his father sold him to a carpet weaver for $12. Iqbal became a slave, a bonded worker who could never make enough money to buy his freedom. In that carpet factory in Pakistan, this preschool-age boy began a grueling existence much like that of hundreds of thousands of children in other carpet factories in Pakistan, India, and Nepal. He was set to weaving rugs and tying tiny knots for more than twelve hours a day, seven days a week, with meager food and poor sleeping conditions, while being constantly beaten and verbally abused.

Six years later, at the age of ten, Iqbal managed to escape and was fortunate to be able to attend a school for freed bonded children, where he was a bright and energetic student. Iqbal began to speak out against child labor. His dream for the future was to become a lawyer, so he could continue to fight for freedom on behalf of Pakistan’s seven and a half million illegally enslaved children. One day, while riding his bicycle with his friends, Iqbal was shot and killed. He was twelve years old. It is widely thought he was killed by factory owners for trying to change the system.

Even though Iqbal’s story is over two decades old, conditions haven’t changed much for impoverished children in developing countries since then, as I found out through more research.Even today, throughout Asia and elsewhere, children as young as four or five are routinely forced to work seven days a week, for twelve to sixteen hours each day, in factories, quarries, rice mills, plantations, mines, and other industries, many of them hazardous, often with only two small meals a day. Most are not allowed out, and they often sleep right where they work. When inspectors come, the children are quickly hidden or told to lie about their age.

Not only are these children denied a childhood and schooling, so most are illiterate, but they very often end up with crippling injuries, respiratory disorders, and chronic pain.

I decided to use my background as teacher of children aged 10 to 14 to organize an anthology of stories aimed at that age group, in hopes that librarians, teachers, and students could influence others to take action. All net proceeds would go directly to a charity that works to help these children regain their childhood and a much better future.

As it would be too difficult to find or write true stories about any of these children, I decided that the best approach would be to organize a variety of well-researched, compelling fictional stories that would appeal to readers from age 12 and up.

To find writers, I called for submissions through my blog, Facebook, and emails. I was extremely lucky that one of the first people I contacted was Steve Hooley, whom I’d first met through TKZ, then in person while presenting at a conference organized by Steven James in Nashville. Steve is an active member of the TKZ community, a talented writer, and an all-around awesome guy! He helped get the word out to others, including the ACFW. Steve also researched and wrote three fabulous stories for the anthology, depicting South Asian child workers in different situations – a 9-year-old boy who works in a carpet factory, a 12-year-old welder who comes up with an ingenious plan, and a girl who works in a clothing factory that collapses.

Story ideas came in from writers across North America and also from Europe, Australia, and India. Caroline Sciriha from Malta, an educator for whom I was editing a story, got on board early on and contributed two stories and has helped spread the word to educators in Europe. Both Caroline and Steve also acted as valued beta readers for stories from other contributors, helping me decide which to accept and which needed revisions. Steve also talked The Kill Zone’s Joe Hartlaub into reading and reviewing the anthology. TKZ founder Kathryn Lilley was also kind enough to read the stories and write an endorsement.

I was thrilled by the quality of stories submitted by talented writers from all over. Other story contributors include Tom Combs, MD, thriller author, also a regular reader/commenter here at TKZ, and award-winning international journalist Peter Eichstaedt, whose contribution is based on true events he encountered. We were also fortunate to entice prolific, talented author Timothy Hallinan to write a powerful Foreword to the book.

Other talented contributing writers not already mentioned above: Lori Duffy Foster, Barbara Hawley, D. Ansing, Kym McNabney, Edward Branley, Fern G.Z. Carr, Eileen Hopkins, Sanjay Deshmukh, Della Barrett, E.M. Eastick, Rayne Kaa Hedberg, Patricia Anne Elford, Hazel Bennett, Sarah Hausman, and myself.

My challenges as organizer and editor included helping with research to make sure the stories depicted real situations in a broad cross-section of labor sectors where children are used as slave workers. And, for the stories to get widely read, I needed to make sure that, although true to life, they weren’t all depressing. The talented writers created characters that came to life and found a variety of realistic ways to insert hope into each story.

The stories needed to be evaluated and edited, with versions going back and forth several times. The contributors, besides having an opportunity to be published in a high-quality anthology, all gained by working with a professional editor and receiving advice that would improve their writing skills in general. Our dedicated, talented beta readers included other contributors and volunteer readers from South Asia.

Surprisingly, one of my most difficult tasks was to find a charity that would allow us to use their name on the book in exchange for donating all net proceeds to their cause. Having a specific, respected charity on board of course increases credibility and sales. Many charities, such as GoodWeave.org, replied that they just didn’t have the personnel to read the book carefully to make sure the children’s stories were handled appropriately and sensitively. Fortunately, we were finally accepted by SOS Children’s Villages, a highly reputable charity that helps impoverished and disadvantaged children all over the world.

As a writer, submitting to an anthology, besides an opportunity to work with an editor to polish your writing and get a story published, can also broaden the scope of your writing, let you experiment with different voices, and, in the case of an anthology for a good cause, provide you with a great way to make a difference in the world.

A little about this project:

Childhood Regained – Stories of Hope for Asian Child Workers aims to bring to life some of the situations children in India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh still face today, in 2016. The captivating, touching stories, each told from one child’s point of view, depict situations for children and young teenagers in garment factories, stone quarries, brickyards, jewelry factories, carpet factories, farms, mines, welding, the service industry, hotels, street vending, sifting through garbage, and other situations. The book also includes several appendices, including factual information on each topic and story questions and answers, as well as lists of organizations that help these victimized kids to regain their childhood.

How you can help child laborers in developing countries: Spread the word about this anthology, especially to teachers of 11- to 14-year-olds and school librarians. I’ll be glad to send a free PDF or e-copy of this book to any interested middle-grade or junior high school teachers, other educators, or librarians. I’ll also send out free sample print copies to educators and librarians in North America. Please have them contact me at: info@JodieRenner.com. We’re in the process of creating a MIDDLE SCHOOL EDITION, so we especially welcome feedback from middle-grade teachers. Thanks for your help!

For more information on Childhood Regained – Stories of Hope for Asian Child Workers, go to its page on my website or on Amazon. The e-book is ON SALE for $0.99 today through Monday.

Jodie Renner, a TKZ alumna, is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources, Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage, and has organized and edited two anthologies for charity: Voices from the Valleys and Childhood Regained – Stories of Hope for Asian Child Workers. You can find Jodie at Facebook and Twitter, and at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, or her blog, Resources for Writers.

Jodie Renner, a TKZ alumna, is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources, Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage, and has organized and edited two anthologies for charity: Voices from the Valleys and Childhood Regained – Stories of Hope for Asian Child Workers. You can find Jodie at Facebook and Twitter, and at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, or her blog, Resources for Writers.

Let’s turn our thoughts today to the subject of happiness and finding inner peace. What’s your go-to method for achieving balance and harmony in life? Does the discipline of writing help you stay balanced and impact your mood in a positive way, or is it more like a daily chore?

Let’s turn our thoughts today to the subject of happiness and finding inner peace. What’s your go-to method for achieving balance and harmony in life? Does the discipline of writing help you stay balanced and impact your mood in a positive way, or is it more like a daily chore?

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000039_00007]](https://killzoneblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/CHILDHOOD_3_full-202x300.jpg)