Protagonists, antagonists and supporting characters– without some version of each, it would be very difficult to write a thriller, and even harder to write a murder mystery. Protagonists must tackle the obstacles they face, with strength of will, usually sooner rather than later. Antagonists must throw up roadblocks; oppose, fight, scheme, betray, whatever it takes to get what they want, depending upon the character. Let’s not forget supporting characters—both protagonists and antagonists need them.

In today’s Words of Wisdom, James Scott Bell discusses that strength of will every protagonist needs, while Jodie Renner dives into creating a fascinating, believable antagonist. Finally, Joe Moore talks about the challenge of removing a character you realize is unnecessary to your novel. This last was something I had to do with my most recent novel, erasing no fewer than three supporting characters, because each turned out to be unnecessary.

As always, it’s worth reading the full posts, which are date-linked from their respective excerpts.

There is no novel, no drama, no conflict, no story without a Lead character fighting a battle through the exercise of his will.

As Lajos Egri states in his classic, The Art of Dramatic Writing:

A weak character cannot carry the burden of protracted conflict in a play. He cannot support a play. We are forced, then, to discard such a character as a protagonist … the dramatist needs not only characters who are willing to put up a fight for their convictions. He needs characters who have the strength, the stamina, to carry this fight to its logical conclusion.

Let’s think about Scarlett O’Hara for a moment. Do we want 200 pages of her sitting on her porch flirting with the local boys? Do we want to listen to her selfish prattle or watch her flit around in big-hoop dresses?

I’m not sure we want anything to do with her at all after seven pages or so, but then! She learns that Ashley Wilkes, her ideal, her dream husband-to-be, is going to marry that mousy Melanie!

She immediately lays plans to get him alone at the big barbecue. She’ll tell him of her love and he’ll dump Melanie. Through strength of will she draws him into a room where they can be alone.

Only her plan does not work out as intended. Which is good! For strength of will must be met with further obstacles and challenges and setbacks. The protagonist has to keep fighting, or the book is over.

That’s why, after the setback with Ashley, Scarlett faces a further complication—a little thing I like to call the Civil War.

For the rest of the book Scarlett will have to show strength of will to save the family home and fight for the man she loves (NOTE: strength of will does not always mean strength of insight. Scarlett does not realize until it’s too late who she really loves. Of course, we could have told her. It’s the guy who looks like Clark Gable!)

Now, a character can start passive. But she cannot stay there for long. In Stephen King’s Rose Madder, the opening chapter depicts a wife who is horribly abused by her psycho husband. The chapter ends with the chilling line: Rose McClendon Daniels slept within her husband’s madness for nine more years.

Wise storyteller that he is, King does not give us more pages of abuse. No, he quickly gets us to a blood stain. It’s what Rose sees on a sheet as she makes the bed one morning, a reminder of her most recent beating. Nothing she hasn’t seen before, only this time it triggers something inside her:

She looked at the spot of blood, feeling unaccustomed resentment throbbing in her head, feeling something else, a pins-and-needles tingle, not knowing this was the way you felt when you finally woke up.

Then comes Rose’s strength of will. She finally does what her husband has strictly forbidden—leave the house. Do that, he warns, and I’ll track you down and kill you.

For us, walking out a door is a small thing, but for Rose Daniels it is the biggest risk of her life. But she does it.

And that’s why we want to watch her for the rest of the book. She will have to exercise her will many times in order to survive.

James Scott Bell—October 25, 2015

To pose a credible, significant threat and cause readers to worry, your antagonist should be as clever, powerful, and determined as your protagonist. Challenges and troubles are what make your main character intriguing, compel her to be the best she can be. They force her to draw on resources she never knew she had in order to survive, defeat evil, or attain her goals.

For today’s post, we’ll assume your antagonist is a villain – a mean, even despicable, destructive character we definitely don’t want to root for. He needs to be a formidable obstacle to the protagonist’s goals or a menace to the hero’s loved ones or other innocents. And thrillers, fantasy, and horror require really frightening, nasty villains.

Most of the bad guys in movies and books want the same thing: power. Or maybe revenge or riches. And they don’t care who gets hurt along the way. Or worse, they enjoy causing pain, even torturing their victims.

The antagonist needs to be powerful, a game-changer. As Chuck Wendig says in his excellent blog post “25 Things You Should Know About Antagonists,” “The antagonist is there to push and pull the sequence of events into an arrangement that pleases him. He makes trouble for the protagonist. He is the one upping the stakes. He is the one changing the game and making it harder.”

The protagonist and antagonist have clashing motivations. Their needs, values, and desires are at odds. The antagonist and protagonist could have completely opposite backgrounds and personalities for contrast – or be uncomfortably similar, to show how close the protagonist came or could come to passing over to the dark side.

Most readers are no longer intrigued by “mwoo-ha-ha,” all-evil antagonists, like Captain Hook in Peter Pan. Unless you’re writing middle-grade fiction, be sure your villain isn’t unexplainably horrid, evil for the sake of evil. Today’s sophisticated readers are looking for an antagonist who’s more complex, realistic, and believable.

Chuck Wendig suggests antagonists should be depicted as real people with real problems: “People with wants, needs, fears, motivations. People with families and friends and their own enemies. They’re full-blooded, full-bodied characters. They’re not single-minded villains twirling greasy mustaches.”

For a believable, fascinating antagonist or villain, try to create a unique, memorable bad guy of a type that hasn’t been done to death. Try to give him or her an original background and voice.

Remember that the antagonist is the hero of his own story. He thinks he’s right. He justifies his actions somehow, whether it’s revenge, a thirst for power, ridding society of undesirables, or payback. He may even feel he has a noble or just goal, as in the serial killer of prostitutes.

Jodie Renner—March 9, 2015

Lynn and I write thrillers with complex plots, and THE PHOENIX APOSTLES is turning out to be the most complex of all. Because of the complexity, we have some really intense brainstorming sessions, especially as we approach the end of the book and must tie all the loose ends together so they are resolved for the reader. Our conference calls go on for hours as we play “what if”, argue, plot, and strategize. Since we live over 300 miles apart and only meet once or twice a year, we rely on unlimited long distance calling to work out the details.

Recently, we were discussing how each of our characters would resolve at the climax of the book. We both like big Hollywood endings, and this one is shaping up to be a whopper. We were going down the list of ever character, either signing their death warrants or letting them live another day. We knew what should happen to Carlos, but when we got to Teresa, we came up short. As a matter of fact, we couldn’t even justify placing her in the final scene. Normally, we assign all our characters “jobs” in each scene, and she was pretty much unemployed by the time the shit hit the fan.

There was a long silence on the phone. Then Lynn asked that dreaded question no self-respecting fictional character ever wants to hear. “Do we really need her?”

“You mean in the climax?”

“No, in the book?”

After another long pause, I had to admit she was right. If Teresa vanished from the pages of our novel, would it make any difference? The reluctant but honest answer was, no.

We came to the conclusion that we could convert all of Teresa’s “jobs” into the Carlos character and the result would be a tighter, crisper story with fewer heads to hop between.

And so the killing began.

Within a few hours, I had gone through the entire manuscript, found every instance of Teresa’s character, rewrote each one and shifting her responsibilities, motivations, and character development to Carlos. By sundown, Teresa was pronounced dead. Worse than dead; like some former Soviet government official who fell out of favor, she simply ceased to exist.

I had lived with Teresa for over a year. I knew her wants and needs. I liked her. But I had to sacrifice her to make for a better story. I mourned her passing, drank some whisky, and moved on.

R.I.P Teresa Castillo.

Joe Moore—July 1, 2009

***

There you have it, advice dealing with protagonists, antagonists and unnecessary characters.

- How have you shown your protagonist’s strength of will? Do you have a favorite example from fiction or film of this in action?

- How do you like to bring your antagonist to life? What’s the most fun aspect of creating an antagonist for you?

- Have you ever had to erase a character from one of your novels or stories? How much work was it? Any advice?

***

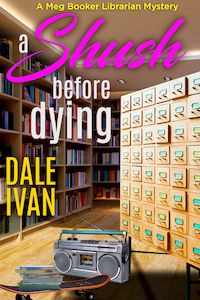

Brand-new librarian Meg Booker is just supposed to be checking out books.

Instead, it’s the patrons who are being checked out–permanently.

A Shush Before Dying, the first book in my new cozy library mystery series set in the 1980s, is now out, and available in ebook and print.

Thanks for another great post. I have a few questions. We talk often about protagonists and antagonists, but supporting characters don’t come up as often.

I’d just like to hear from other TKZers specifically on the matter of writing a series and use of supporting characters:

1) Do you tend to plan your supporting characters in advance or do they just happen as you go? I’m assuming most develop them as they go, whether plotters or not, but would love to hear thoughts on this.

2) Joe’s segment re: his character Teresa Castillo touches on this but do authors have other measuring sticks for assessing the usefulness of supporting characters?

3) What do you do if writing a series & you need to tweak a supporting character mid-series? i.e. are there any tricks to building supporting characters that let them expand as the stories in your series expands?

I guess what I’m saying is I’d like to get inside your heads and see how you’ve wrestled with supporting characters that occur in more than one book and how you maximize their use to build story-world. 😎

Terrific questions, BK. Terry has commented below, and hopefully others will weigh in.

#1 and #3 For my part, my supporting characters tend to be a combination of planned in advance and happen as I go, but Book 1 typically lays out much of the supporting cast. In my Empowered series, I knew my hero Mat, would have her handler boss Winterfield from the secretive government agency Support, and the handsome undercover support agent Alexander Sanchez who was her contact while she infiltrated the Scourge. There, she met Keisha—created in book 1 as a supporting antagonist who later became her best friend. My answer to #2 is that you can have an episode that effects the supporting character and changes her—that happened to Keisha in a later book, mirroring Mat’s own arc in fact. Deepening the character by giving more background can also set up the change.

#2. There’s a supporting cast in my Meg Booker Librarian Mysteries, with built in mysteries for one in particular. My challenge in the first novel was to not have too many characters. Like I noted above, I erased three. The metric was not only usefulness, but also simply being able to track them. I had a large cast and my beta readers were having trouble tracking the minor ones, so three supporting characters went. Much of the novel takes place at the library branch, but I needed to slim down the crew so that the readers could follow a few.

Dale, thanks for weighing in on the supporting characters. What your comment makes me realize is that while I can’t anticipate or foresee all potential use of supporting characters over the course of books (at least not at this stage of my relatively disorganized writer’s life 8-), I can take time to sit down and think about possible character arcs/story lines for supporting characters the same way we think about those things for the protag/antag. I’m gonna put that on my list of things to do as I work through the revision process of book 1.

In the convention of romance “series” which are really connected books, supporting characters get their turns center stage in subsequent books. I do this in my Blackthorne series. Book 1. When Danger Calls, has Ryan as protagonist, with Dalton in a supporting role. Book 2, Where Danger Hides, features Dalton, and on through the series.

If you want to see someone who really knows how to do this, read the In Death series by JD Robb. Her cast has expanded tremendously throughout the series.

For my Mapleton mysteries, as I bring in characters–given the series revolves around a small town police force, I have to include other officers–their roles expand, their personalities grow with each book.

Example: Titch showed up as an officer as different from Gordon as I could make him. Little by little, book by book, he’s showing up more, his personality is developing, and I think he adds another character dimension to the stories.

I’ve also given some of them starring roles in novellas.

But did I plan it? Sorry, no. They simply show up and ask for more page time. This probably doesn’t answer your question, but it’s the way things have worked out for me.

Great answers, Terry! I love the organic progression of your series cast. That’s one of the things I want to show in my mystery series.

Thanks, Terry. I will check out the above mentioned books. As I think about this topic it reminds me that this is yet another reason that writing is so much fun—in addition to your protag/antag, there are endless possibilities regarding what you might do in a future book with a supporting character. World-building can feel daunting but it’s also rewarding when you pull it off.

Great collection of posts from the archives, Dale. Excellent points. Excellent review for all of us.

1. Showing the protagonist’s strength of will: In my teen fantasy series, Bolt has Becker Muscular Dystrophy and must overcome physical handicaps to take on the antagonists. Of course, he has learned native American magic and has a flying barrel cart.

2. Creating an antagonist: In my Mad River Magic series, conflict is created by unusual events that are destroying the local community (or the country). I work backwards to create a strange/unusual antagonist with the skills and the motivation to cause changes in his own magic world that are spilling over into the real world.

3. Removing characters: The few times I have needed to remove a character, I combined two character into one. The biggest challenge was making certain I removed all references to the character. The “Find” function really comes in handy.

Thanks for searching the archives and putting these posts into themes for our benefit. We really appreciate it, Dale!

You are very welcome, Steve. Thanks for these detailed answers—really useful examples. I used Find as well to remove my three characters, but also kept an eye out as I did my proofing pass.

Wonderful selection, Dale. I saved this post (and related links) for a new project taking shape in my mind.

Villains and/or antagonists are the most fun and challenging to write b/c their values and goals in many cases are outside of the law and against accepted social morality. Why do they step over that line? Why do they take chances that could land them in prison?

To respond to Brenda’s question: my supporting characters emerge organically, like Terry’s. They are family and friends of two lead characters who show up in everyday life. Several children of the main characters have taken the spotlight in different books b/c their actions are inciting incidents. In the third book, Tillman’s daughter attempts suicide and is saved by Tawny. In the sixth book, the parents of Tawny’s best friend get into deep trouble. In the eighth book, Tillman’s son pulls a stunt that will later tie into the main plot problem of deep fakes.

Supporting characters have to earn their keep. They’re not simply props that the author plucks out of central casting. If they don’t have a function connected to the story, they don’t belong there.

Like Joe, I’ve combined several minor characters. That solves the problem of a character who might be interesting but is irrelevant. When melded with another character who is relevant, that eliminates the unnecessary person and creates a stronger supporting character.

Thanks, Debbie. I’m glad this post and the links are keepers. I love reading your answers–more helpful insight for Brenda, and the rest of us. You have a compelling supporting character series arc (for want of a better term) which is a great model. Organic is a great way to go, even for this outliner.

I so agree that supporting characters need to earn their keep, plain and simple. They can always be saved for later. Melding them together is a great approach.

Thanks, Debbie. I suspect there are going to be a couple of instances where I start out thinking the supporting character is earning their keep but may end up having to combine characters as discussed or dump them because I didn’t use them the way I thought I would.

Too bad we just can’t be all-seeing and all-knowing from the start of the book as we write. LOL!!!!

Brenda, all-seeing and all-knowing would take the fun out of writing! 😉

Yes, I believe you’re right. Would suck out all the motivation and curiosity.

❖ How have you shown your protagonist’s strength of will? Do you have a favorite example from fiction or film of this in action?

❦ Tenirax, even after having been introduced by Bishop Filippo to Bungorolo the Torturer and his favorite mechanism, still concocts an elaborate fictitious relic to fool the Bishop. Is this strength of Will? Or merely an insane whim?

❖ How do you like to bring your antagonist to life? What’s the most fun aspect of creating an antagonist for you?

❦ Tenirax is a picaresque novel. I bring him to life by having him do what picaros do: He travels a lot to escape the consequences of his practical jokes, and he doesn’t invite an antagonist to tag along. Why would he? The antagonist is Tenirax’s own rebellious nature and quirky sense of humor. We soon learn that he is unable to quell his rascality when he creates a counterfeit Saint, San Juan de Sagrada Nada. The fun lies in Tenirax getting in trouble at the end of every chapter and getting out of it in the next.

❖ Have you ever had to erase a character from one of your novels or stories? How much work was it? Any advice?

❦ Nope. Once they come, they stay. An example of a necessary “extra” character would be Red Harrington in my thriller screenplay, The Paranormal Patient. It is left to the reader to figure out Red’s purpose. (His name is just a place-holder. He may eventually get a different moniker.)

Thanks for weighing in JG—great comments!

Another great post, Dale. I also enjoyed reading everyone’s comments.

Protag: In my second novel, Dead Man’s Watch the main character feels obligated to a friend who was suspected of murder, and she puts herself at risk to help him.

Antag: Because I write mysteries, the antagonist is not known to the audience until the climactic scene. The reader has to try to figure it out along the way. The denouement explains all the nefarious things the villain did.

I think secondary characters are great opportunities to add spice and humor to a novel. While the main characters are trying to solve a crime, the supporting cast can cause problems and foul up the works with good intentions.

Thanks, Kay. Excellent point about the antagonist in the mystery—they are hidden in plain sight. They can also be a bit a of a shapeshifter—appearing as something benign when in reality, they are the cause of death and sorrow in this story. There’s something mythic about their role in a mystery.

I love this take on the supporting cast—I agree completely!