Not Even More Rules

Terry Odell

If there’s one “rule” of writing, especially in these days of indie publishing, it’s that there are no rules. Want to leave out quotation marks? Go for it. Want to replace them with dashes? Why not? Want to publish without any eyes but your own on the prose? Do your thing.

And, in these days of indie publishing, we can split these ‘rules’ into two basic categories. Rules of writing, which lean toward grammar conventions, and rules of publishing, which relate to what happens once the book is set loose into the world of readers.

Since there was a recent post about Heinlein’s rules, I’m following up with these from Kurt Vonnegut, which, as did Heinlein’s, relate more to the publishing side of things.

8 Rules for Writing

- Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

- Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

- Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

- Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.

- Start as close to the end as possible.

- Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them-in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

- Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

- Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

— Kurt Vonnegut: Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons 1999), 9-10.

My personal thoughts and interpretations:

- The last thing I want is to hear someone saying, “well, there are XX hours I’ll never get back” after reading one of my books.

- Totally agree. It’s all about the characters for me, and I give readers more than one.

- We’ve heard this one a lot, both here at TKZ and at a myriad of other writing sites. Enough said.

- Need to remember this one. Wandering down Happy Lane in Happy Town doesn’t do much for book pacing.

- Yep, we’ve heard this one a lot, too. My self-measured progress as a writer was how much less I had to cut from the beginnings of my books.

- Another familiar one. Put your character up a tree and throw rocks at them. Or shoot at them.

- This one sits at the top of my list when I hit the editing phase. Don’t second guess yourself. Some readers will have issues with something in your book, be it a character who reminds them of their ex, or setting, or POV, or tense, or anything else. Let it go. Write your

- Not sure how to interpret this one. As writers focused on mysteries and suspense, we want that twist, that surprise.

Seems to me, we each make up our own rules, be it on the production side or the story side. We do what works for us, writing the best story we can by our personal standards.

Any of Vonnegut’s rules resonate with you? In either direction?

**Anyone going to Left Coast Crime in Tucson? Would love to meet!

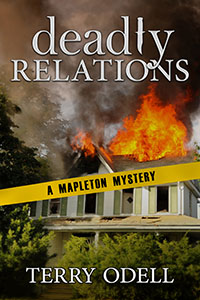

Deadly Relations.

Nothing Ever Happens in Mapleton … Until it Does

Gordon Hepler, Mapleton, Colorado’s Police Chief, is called away from a quiet Sunday with his wife to an emergency situation at the home he’s planning to sell. A man has chained himself to the front porch, threatening to set off an explosive.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Actually, the first one:

“Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.”

…applies to more than just writing…

And having read many, if not most, of KV’s works, I sometimes wonder if he practiced what he preached in regards to number 8… “…Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages…”

Hi ho…

Thanks, George –

Maybe the reader’s story finishes wouldn’t be what Vonnegut had in mind, but they’d be satisfied with the conclusion they predicted.

Reminds me of the M*A*S*H episode where the gang was passing around a mystery and the last pages were missing. They ended up tracking down and calling the author … (spoiler alert) … who said she didn’t remember the book at all.

As George mentioned above, Rule #1, respecting people’s time is something I want people to do ALL the time. Knowing how strapped for time I always am, I want people to respect it & I want to do the same for them. This one is by far the most important takeaway in Vonnegut’s list.

RE: Every character should want something–that’s easier with the main characters, but I can tend to forget that with minor characters.

Rule #6 is the one I need to pay most attention to. I always have to fight the urge to be too nice to my characters. Great in real life, not so great for fiction. LOL!

As to Rule #8, I get writing with clarity, but his rule #8 in itself lacks clarity–why on earth would you not want suspense (therefore tension) regardless of genre?

Morning, BK. Thanks for dropping by. I agree that it can be tough to throw rocks at our characters … my first (short-lived) critiquer told me I had to stop making bad stuff happen to my heroine.

Perhaps ‘suspense’ didn’t mean the same as ‘tension.’

On the last one, people like to anticipate what’s going to happen. There’s a certain satisfaction in “getting” the foreshadowing. Anne Rice had a tendency to take an unexpected left turn at the end of her books which usually left me wanting to throw the book at the wall. Keep ‘em guessing, but it goes back to giving readers someone to root for, even if its the “who dunnit,”

Thanks Karla. I think there’s a fine line between “Never saw that coming” and “I knew it” for readers. They should be able to go back and say, “Ah, there it was.” Subtle foreshadowing rules!

Great post, Terry.

It looks like #8 is going to be the topic of conversation this morning.

I agree with Karla, and you. (For me) #8 is saying that we need to set things up (foreshadowing) such that there are certain things that will need to happen at the end of the story in order for the reader to feel satisfied. The reader will be constantly guessing what the twists and turns will be. And the goal of the writer is to give the reader the satisfaction, but with a curve ball (twist) they didn’t see coming.

Thanks for a great post.

Glad you’ve enjoyed today’s topic. Yes, #8 will be the conversation-starter. There are genre expectations but approaching them with that ‘twist’ can keep readers coming back.

Elmore Leonard has a good set of ten rules that are worth hearkening to.

I’m pretty good on grammar and composition, having had some damned good teachers in grade school and high school.

I stick to two pub auth generalities and in the things I write they tend to emerge as if by magic. I reckon that writing a cracking good story takes care of most everything else.

John Dufresne says only trouble is interesting. Great Ted Talk as well.

Leonard Gardner in his Paris Review Interview said this:

“I never wanted to write about society people or something like that. I was interested in the rougher side of life. There’s something about struggling people, poor people, that’s dramatic. Struggle is dramatic. I’ve had friends who wrote pretty good novels about college boys and college professors. I didn’t dislike them. But it’s a matter of drama. For a lot of people, real life is a struggle. Maybe wealthy people suffer, but if you read a book about their suffering—a multimillionaire’s wife is divorcing him or something—it’s just different to me. It’s not as desperate as drama set in poverty.”

Thanks for the Leonard Gardner quote, Robert. And I think a lot of what people want to read depends on where they are in their own lives at the time. I read more to escape than anything else, so when the world around me is filled with violence, I don’t want to read (or write) about it. Hence the lack of a homicide in my latest book.

Yeah, Terry, # 8 violates my own rule: Act first it, explain later.

# 3 is good but incomplete. Not only should each character want something in a scene, there should be someone with an opposing agenda. That makes for conflict.

So true, JSB. And there should be the ‘what happens if the character gets what he (thinks he) wants’ conflict as well. Give him choices–between it sucks and it’s suckier, per Deb Dixon.

Great topic, Terry.

Like everyone else, I don’t understand #8. Seems to be the exact opposite of the need to keep ’em guessing. Maybe Vonnegut wanted to keep us guessing about what he meant.

That’s as good an explanation as any, Kay!

Good morning, Terry. I’m with you and the others on not agreeing with Rule #8. Not only does it remove suspense, it could also lead to a series case of info dump if handled poorly. Of course, info dumping is always a risk, especially when a lot of world building is required, say historical mystery or epic fantasy.

Rule #7 is important–don’t try to write for everyone, but pick a reader. The challenge is if that reader is also the writer. There is nothing wrong with writing for your reader self. However, you need to make sure you have included what is needed for another reader to be able to build that story as they read. Being able to view my own work as a reader other than myself took time and practice.

I wish I was attending Left Coast Crime in Tucson–it would be wonderful to meet you in person. Have a fantastic convention!

Good points, Dale (and wish I could meet you, too). I think I try to write for my baseline demographic rather than a single reader, which means trying to hit the important reader expectations for the genre, and things I’ve established for my series.

I agree with the others who have commented that #1 should be a rule in all phases of our life. #8 rang my bell because I read (and write) mysteries. In reading them, I’m in competition with the characters to decide “who dunnit” first. In writing them, I strive to keep readers guessing.

It’s looking like I could have done the entire post on KV’s rule #8, and how we interpret it. This being a mystery-focused blog, it’s possible (probably) we see things differently

Hi Terry,

Of course, I wrote that guest post on Heinlein’s Rules, and readers can still find the full essay at https://hestanbrough.com/the-daily-journal-archives-gifts-dvds/. Like my Journal archives and the other gifts on that page, they are forever free.

You wrote, “I’m following up with these [rules] from Kurt Vonnegut, which, as did Heinlein’s, relate more to the publishing side of things.”

I assume where you wrote “publishing” in the quote above you meant to write “writing.” Either that or I’m thoroughly confused.

As far as I can tell from Kurt Vonnegut’s rules for writing above, all of them are about writing. They’re even titled “8 Rules for Writing.”

As for Heinlein’s Business Habits for Writers, they aren’t about writing at all, except to do it (1 and 2) and to not second-guess yourself (3). But they aren’t about publishing (or seeking publication) at all either except, again, to do it (4, Put it on the market; and 5, Leave it on the market).

Nowhere does Heinlein talk about how to write anything: setting; major, minor or transitional scenes; hooks or openings or cliffhangers; grounding the reader; invoking the POV character’s physical or emotional senses; the POV character’s all-important opinion of the setting; pacing; tension; the rule of three; the uses of repetition;reader expectations per genre; tropes per genre; etc. etc. etc.

But even having kept his advice that simple—5 solid business habits presented in only 34 words—he then admitted, “The above five rules … are amazingly hard to follow—which is why there are so few professional writers and so many aspirants….”

I doubt anyone can dispute that. I personally suspect of 10,000 would-be fiction writers, probably over 90% are knocked out by Rules 1 and 2 alone. Whether or not a writer chooses to follow Rule 3, probably 90% of the remaining 10% or fewer writers are knocked out by Rule 4. (I present these percentages only as my casual approximation, not as a “finding” of any sort of scientific poll or study.)

Interested parties can find Heinlein’s original essay in Of Worlds Beyond: The Science of Science Fiction Writing (Fantasy Press, 1947).

My ‘definitions’ when I wrote this post: “Writing” = Craft

“Publishing” = Getting it into the hands of readers.

7. Most of us are genre writers, here, so we are writing for a genre audience and their expectations. That’s our one reader. No sane romance writer ends the book with the couple breaking up. No sane mystery writer has their sleuth shrug his shoulders at the end and say, “I haven’t a clue who did it.”

8. This sounds like an excuse for info dumping. That’s bad. Instead, we give the reader just what they need at the moment and allow them to infer everything else. The story is a puzzle for the reader as well as for the main character. If we give the reader everything, they get bored because they are no longer figuring things out. It also insults their intelligence.

Exactly, Marilynn. Too bad we can’t go ask KV to elaborate on #8

I’m with you and Jim on #8. I don’t get that one at all. Maybe he just wanted a nicer rounder number and 8 was enough. The art of suspense is knowing when and what to withhold, imho.

Precisely, Kris. (which is why there ‘are no rules.’) Guidelines, suggestions, talking points maybe, but every writer follows the ‘rules’ that word for them.

I add one of my own: Never confuse the reader – except on purpose.

There’s enough in my mainstream fiction to keep track of without it being accidentally obscure, too. My beta reader occasionally flags one – and we’re about 50/50 at needing a rewording once I explain.

And I’m okay with V’s #8: I tell readers right in the 145 word prologue to the first novel in the trilogy exactly what’s going to happen – to keep them wondering for the first two books exactly when and how is that going to happen, and for most of the third, how the heck are they going to get out of that one.

Interesting approach, Alicia. I’m not fond of knowing what’s going to happen because instead of being absorbed in the story, part of me is wondering/searching/waiting for that reveal.

There are very specific reasons for it:

1) The prologue is part of an overarching story which appears years later in The New Yorker – and gets some key parts of the story wrong. The reader will know which parts.

2) I’m grooming the reader to accept the style of the books, which is to have a layer of the story, the outside part, happen outside: in the prologues (1 per volume of the trilogy), the chapter epigraphs, and the epilogue in the final volume; in the same way people observe the shenanigans in the way we view Hollywood and actors – and follow and have opinions on things we have no knowledge of.

There’s a tension between being absorbed in the story, and having this odd bit of foreknowledge, and wondering how it could possibly happen. A measuring stick, as it were.