Bloodstain Pattern Analysis is the forensic interpretation of human blood evidence in crime scene investigations. It’s used to recreate actions that caused the bloodshed. Because blood has chemical properties that behave according to specific laws, trained analysts can examine the size, shape, and distribution of bloodstains to draw conclusions of what did—or did not—happen.

Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (BPA) applies the sciences of anatomy, biology, chemistry, mathematics, and physics to answer questions like:

- Where’d the blood come from?

- Who’d it belong to?

- How’d it get there?

- What caused the wound(s)?

- From what direction was the victim assailed?

- How were the victim and perpetrator positioned?

- How many victims and perpetrators were there?

- What movements were made after the bloodshed?

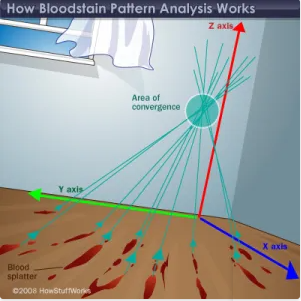

You’ve seen the CSI shows where investigators, dressed in their ‘bunny suits’, photograph drops, streaks, smears, and pools of blood, then swab for DNA and String the room back to Area of Convergence points. Well, that’s pretty much how it happens, except today most Stringing is done by 3D computerization.

You’ve seen the CSI shows where investigators, dressed in their ‘bunny suits’, photograph drops, streaks, smears, and pools of blood, then swab for DNA and String the room back to Area of Convergence points. Well, that’s pretty much how it happens, except today most Stringing is done by 3D computerization.

Bloodstain pattern interpretation is nothing new. It’s been around two hundred years and became increasing sophisticated as technology advanced. I’ve been involved in a number of BPA examinations during my time as a cop and coroner. One that really stands out was when Billy Ray Shaughnessey axe-murdered his ex-girlfriend and her new lover. The room looked like a bomb went off in a red paint factory. I’ll tell you more about it at the end of this article. First, let’s look at how blood behaves.

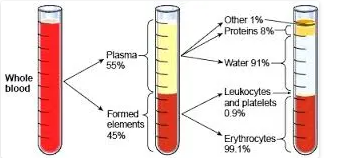

Blood has three components that are suspended in plasma.

Erythrocytes are your red cells that transfer oxygen through hemoglobin. It’s what gives blood the red color. Leukocytes, your white cells, are your body’s defenders and support your immune system in fighting infection and disease. Platelets are formed in your bone marrow and play a major role in hemostasis or plugging up breaches in vessels.

Blood composition is about 55% plasma and 45% formed elements, or cells, which remain suspended due to agitation caused by your circulatory system. That’s called viscosity—it’s density or internal friction. Once blood leaves your body’s pressurized containment, it’s subject to the forces of gravity and surface tension which dictates its resting shape. That can be in drops, streaks, or pools.

Crime scene bloodstains take different forms due to factors like velocity and distance of travel, amount of blood flow, angle of impact, and type of surface or target it lands on. There are eight categories of bloodstain patterns:

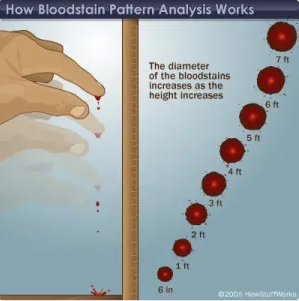

Single Drop — These stains are typically from a vertical fall and under low velocity, like when your cut your finger and blood drips to the floor. Blood molecules are very cohesive. They attract and bind in a surface tension that makes a sphere. The drop stays in a ball until it strikes an object or a force acts on it. This is called bleed-out.

Single Drop — These stains are typically from a vertical fall and under low velocity, like when your cut your finger and blood drips to the floor. Blood molecules are very cohesive. They attract and bind in a surface tension that makes a sphere. The drop stays in a ball until it strikes an object or a force acts on it. This is called bleed-out.

Impact Spatter – These result from forceful impacts between an object and wet blood, causing the blood to break into little droplets. Greater force produces smaller droplets. The study of impact staining provides huge insight into the relative positions of individuals and objects involved in the crime. There are three sub-categories of impacts:

1. Low Velocity Impact Spatter (LVIS) — Also called Passive Impact Spatters, these are the largest bloodstain drops with a diameter of 4mm or greater. They travel at a slow speed, no greater than 1.5 m/s. They’re associated with being struck by a large, blunt instrument such as a chair or leaking from an open wound. They’re also formed when a large amount of blood has been transferred to another surface and the excess drips down.

2. Medium Velocity Impact Spatter (MVIS) — These spatters are associated with an intense beating like from a club, a hammer, a gun butt, or a bag of frozen pork chops. (Yes, I once had a homicide case where a guy’s head was caved-in with a bag of frozen pork chops.) MVIS drops are less than 4mm and get propelled at speeds between 1.5 and 7.5 m/s. The further from the target surface that blood is expelled, the larger the drops will be.

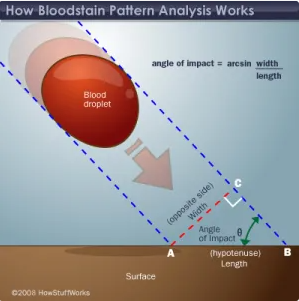

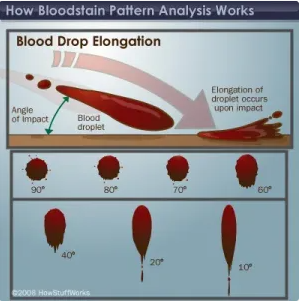

3. High Velocity Impact Spatter (HVIS) — This stain pattern is caused by gunshots, explosions, or contact with high-speed objects like having your throat cut with an electric carving knife. (Had one of those, too.) They’re evident by masses of tiny droplets less than 2mm in diameter and occur at velocities far in excess of 7.5 m/s. There’s no mistaking this type of bloodstain. The angle of impact is evident by an elongated shape – the longer the stain, the longer the angle from vertical.

Cast-Off Stains — COS are common in scenes such as Billy Ray Shaughnessy’s axe-murders where straight and curved lines of blood are made on the walls and ceiling by the centrifugal force of back-and-forth swings. They produce tear-shaped or oblong stains with ‘tails’ that point in the direction of travel. By reversing the line of travel, the path can be traced or stringed to its area of convergence.

Transfer Bloodstains — These are generally patches and smears of blood deposited secondary to the main, violent event. They say a lot about sequence. It can be when a victim tried to crawl away, the body was dragged, the perpetrator placed a bloody hand on a wall, or when he hid the axe in a closet like Billy Ray did. Tell you more about him soon.

Transfer Bloodstains — These are generally patches and smears of blood deposited secondary to the main, violent event. They say a lot about sequence. It can be when a victim tried to crawl away, the body was dragged, the perpetrator placed a bloody hand on a wall, or when he hid the axe in a closet like Billy Ray did. Tell you more about him soon.

Projected Pattern — This is from arterial damage, such as severed carotids, femorals, radials, and brachials where pressurized blood ejaculates via the still-beating heart. You’ll see groups of big to small splotches, usually in an arc pattern. Very common in stabbings.

Pooling — Usually occurs once the victim is unconscious and passively exsanguinates. That’s the fancy term for bleeding to death. Something telling to a Bloodstain Pattern Analyst is where large pools of blood occur in different locations—no doubt the body’s been moved.

Insect Stains — Not long after death, the bugs show up. They land in the bloodstains and make little tracks all over the place. These are easily confused with HVIS to the untrained eye and known in the industry as Flyspeck.

Insect Stains — Not long after death, the bugs show up. They land in the bloodstains and make little tracks all over the place. These are easily confused with HVIS to the untrained eye and known in the industry as Flyspeck.

Expiration Stains — These are incidental bloodstains associated with injuries to the respiratory and abdominal tracts where a gasping victim expels through the mouth or nose. They appear diluted, more brownish in color due to mixture with saliva or mucous, and look like a fine mist.

Examination of a bloody crime scene is a slow and methodical procedure.

The area is still photographed from wide, medium, and close-up angles as well as videoed. Each stain pattern is marked, catalogued, and a swab taken for serology or DNA typing. The patterns are then Strung to their Point Of Origin, or area of convergence, and a complex application of trigonometry begins to tell a compelling tale of just what went down.

The visual absence of blood can be misleading.

Criminals occasionally clean up a scene or there may be only a small bit of blood emitted. Chemical reactive agents like luminol and phenolphthalein can be applied which visualize latent stains. Light spectrum tools, such as LumiLights, are also used to amplify spots not visible to the naked eye.

Getting back to Billy Ray Shaughnessey — This guy hid in his ex’s attic with an axe for two and a half days, waiting to catch her with a new beau. Sure enough, she brought one home from the bar. At 3:00 am, Billy Ray crept down from the hatch, snuck into the bedroom, and chopped them to pieces. Like I said, the crime scene looked like a bomb exploded in a red paint factory.

It took us three days to catch Billy Ray. He did the right thing and fessed-up, then re-enacted the murders on video. It was the coldest thing I’ve seen. Billy Ray described what he did as if he were watching Jason or The Shining, going through repeated motions of chopping, and back-swinging, and chopping some more. He demonstrated with a 2×2 stick as a prop. (We were nervous about giving him a real axe.) He showed how he modified body positions after death, where he hid his axe in the closet, and where he cleaned himself up.

It took us three days to catch Billy Ray. He did the right thing and fessed-up, then re-enacted the murders on video. It was the coldest thing I’ve seen. Billy Ray described what he did as if he were watching Jason or The Shining, going through repeated motions of chopping, and back-swinging, and chopping some more. He demonstrated with a 2×2 stick as a prop. (We were nervous about giving him a real axe.) He showed how he modified body positions after death, where he hid his axe in the closet, and where he cleaned himself up.

Billy Ray did the right thing again. He pleaded guilty, receiving two life sentences.

During the three days we hunted for Billy Ray, the Forensic Identification team sealed the crime scene and independently conducted their Bloodstain Pattern Analysis. Once Billy Ray was done, we (the detective team) compared notes with the forensic team and — unbeknownst to what Billy Ray reenacted — the forensic folks got it bang-on. They’d reconstructed how many blows each victim received, various positions everyone was in, and… who fought back. I was sold on the science ever since.

Here are links to more information on Forensic Bloodstain Pattern Analysis:

A Simplified Guide To Bloodstain Pattern Analysis

The Forensics Library – Bloodstain Pattern Analysis

Principles Of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis – Theory and Practice

Bloodstain Pattern Analysis – Crime Scene Reconstruction

Kill Zoners – Have you used bloodstain pattern analysis in your works? Have you researched this science arm? Wide, wide open to comments.

Garry, thanks for a master class in bloodstain analysis. Wow, what a lot of useful, fascinating info. Definitely bookmarking this post.

No, I haven’t used BPA in my books but this is so interesting, I may have to incorporate it into my WIP. Warning: I’ll be calling a favorite expert!

Good morning, Debbie. I was late posting today and thanks to an email from Steve I realized I’d forgotten to schedule it. BTW, don’t believe everything your favorite expert says. He also writes fiction.

Wow, what a great post, Garry. I’m always awed by the science involved in criminal investigations. Trigonometry? I knew I shoulda paid more attention in high school. Math is everywhere.

In addition to the great breakdown of the forensic process of BPA, I’m once again blown away (no pun intended) by the things humans do to one another. Sometimes it seems like we’re a sad species indeed.

Have a wonderful Thursday…

Thanks, Deb. There’s extensive training goes into BPA. At a detective level we’re taught enough to understand the process and to leave it to the pros to carry out.

Thanks, Garry, for this post. I agree with Debbie – very fascinating.

In answer to your questions, I have not researched or used BPA in my works. But, the next time I run into a bloody body, you can bet I’ll be thinking, “What was that blood pattern, stained trajectory, viscosity dripped, geometry stuff Garry told us about?”

Seriously, this is good stuff. Thanks!

And thanks for the email reminding me to hit the publish button, Steve. Hope you can use the info some time.

Good morning, Garry. I’ll echo Debbie and thank you for providing us with a detailed rundown of bloodstain pattern analysis. This is absolutely fascinating stuff.

I’ve never used it in my fiction, but now I have a reference for if/when I do. Thank you, my friend, for taking the time to break this down for us. Billy Ray sounds like exhibit A for a stone-cold killer.

You mentioned utilizing chemical reactive agents to identify blood stains/spatters that had been cleaned. Is analysis also done to identify any potential cleaning agents, to help prove that a blood stain had been cleaned, or is the reactive agent enough?

Thanks again!

God question about identifying cleaning agents, Dale. Yes, if there was evidence of an agent being used, sampling would be sent for chemical analysis to identify or confirm the substance. Evidence of clean-up would contribute to the perpetrator’s mindset and intent which is a vital legal ingredient in proving guilt.

Sorry, “good” question – not “God” question.

I never wrote police procedural or hard mysteries, but I was the juror wide awake when the CSI evidence was presented. Fascinating stuff. Gun shells and trajectory as well as insect evidence are fascinating, too. Applying modern CSI to historical murders and events is also illuminating.

Good stuff, Garry. I’ve used blood spatter evidence in a couple of my books. Twenty years ago I went to an all-day seminar called “Murder, Mayhem, and Madness.” All about forensics. One presenter was a blood expert from the Sheriff’s lab. The first thing he said was, “Blood tells a story.” I took copious notes, among them:

Asphalt is rough surface, so spatter has little “spikes” (the little spidery stuff all around the spatter. “Satellites” have bounced off further from the parent, like a satellite from a planet.)

Look where blood ISN’T = a “void.”

Juries love to see “stringing.” Where you take the spatters, and put a string to show where body was. Tail on blood stains tells us the origin of the blood source, or “point of convergence.”

Thanks, Jim. “Look where blood isn’t.” Very good point.

Excellent as usual, Garry. I used blood spatter analysis in MARRED and CLEAVED. Fascinating subject. I can lost for days researching this field.

I remember you telling me about the hours you spent rabbit-holing BPA, Sue, and then read my Cliffe’s Notes version when I first posted this piece on DyingWords. BTW, great chatting with you yesterday, and I’m so looking forward to our next collaboration including bringing Billy Ray to life on the screen. It should be fun recreating that bloodbath room. 🙂

Thanks, Garry. This is fascinating, as long as you’re not the donor of the claret.

Author and forensic scientist Lisa Black gave a slide presentation and discussion at a Bouchercon several years ago. The slides showed a bloody trail that involved a kitchen, a hallway, and a bathroom, where a corpse was in repose. It looked as though someone had chased the departed through the house, hacking away at them with a sharp instrument as though they were a redheaded stepchild who at spoken out of turn. It was ultimately concluded that the deceased assumed room temperature as the result of an unfortunate kitchen accident. The victim ran down the hall toward the bathroom, hoping to find something to stop the copious bleeding. Someone, alas, had used the last Curad without replacing the box. Requiescat in pace.

Great comment, Joe. I always look forward to your take. “The redheaded stepchild.” I have a vision of Chuckie in my mind.

Fascinating stuff, Garry! No, I’ve never used any BPA in my books, but I can see a possible application, even in a cozy mystery.

Thanks!

Thanks, Kay. It might well work out in a cozy 🙂

It’s nice to know that even if my arm is broken and I’m unable to slit a throat with the standard knife that I can still get the job done with an electric carving knife. Have to admit I’d never thought of that.

I shall be making sure I have plenty of weaponry in my freezer. Defense only, of course.

In my novel Situation Solved, the detective used bloodstain pattern analysis at the scene in her efforts to determine what happened, where the killer stood, etc. Very interesting stuff, and from a craft perspective, one more way to “focus down” the reader’s attention to pull him/her into the story.

Thank you for this great post! I haven’t used BPA yet, but after reading this I probably will! Like Sue, I can get lost down a rabbit hole of research in a heartbeat!