by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

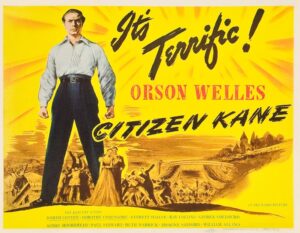

I love Orson Welles. He is one of the few authentic geniuses America has produced in theater and film. At the tender age of 25 he co-wrote and directed what many critics (and your humble scribe) consider the greatest film ever made, Citizen Kane (1941). It was so far ahead of its time that RKO didn’t know how to market it. So they came up with what may be the worst ad line in the history of movies: It’s Terrific!

The movie itself is so good it’s sometimes easy to forget that Welles’s portrayal of the titular character is also one of the great acting performances ever. The guy, in brief, was an amazing talent. Sadly, the studios didn’t get what he was doing and he would have nothing but trouble making films the rest of his life. Still, whenever he did complete a project, it was either a masterpiece or had scenes in it that are unforgettable.

Masterpiece definitely describes Touch of Evil (1958). It was considered by Universal to be a nice little crime movie for Charlton Heston (pre-Ben Hur). No one thought of the material as anything earth shattering. It was based on the novel Badge of Evil by “Whit Masterson,” the pseudonym of crime fiction duo Bob Wade and H. Bill Miller.

Welles was cast as the villain, corrupt police captain Hank Quinlan. This is when the merciful fates of film stepped in. During a phone call between Heston and the producers, Heston suggested that Welles might also direct. Universal asked Welles if he’d like to helm the picture, and Welles said yes, provided he got to re-write the script. Again, considering Welles’s reputation at the time, that Universal acceded to the request makes it seem those movie fates were working overtime.

Touch of Evil, it can be argued, is the last true film noir. But it is so much more. It has the Welles touch all the way through, from the fantastic one-take opening sequence to the shadows and angles Welles did better than anyone. He saw stunning visuals in his prodigious mind and then used whatever camera techniques were available to put them onscreen.

No other director has ever had that singular, Welles imagination.

Then, for some reason, the fates took a coffee break. During the shooting, the studio had seemed very happy with the dailies. But when the rough cut was delivered the honchos got cold feet. Welles was never told why. I suspect that, once again, he was so far ahead of every other filmmaker the studio didn’t how to market the thing. So they took the film away from Welles and did some cutting and re-shooting. Then they ended up releasing it as the B picture on a double bill, with absolutely no advertising. The movie died, and with it any chance that Welles would ever work unhindered in Hollywood again.

But in Europe, especially France, the film was hailed as a triumph. In the 1970s that assessment got to America and now everyone knows it’s a classic.

Throughout his troubled Hollywood existence, Welles somehow kept his youthful ebullience whenever he was interviewed. I encourage you to go on YouTube and search for Welles interviews. They are always smart, funny, charming. Here is one where he talks about Touch of Evil.

In this interview he says something fascinating. Someone remarked to him that Touch of Evil seemed “unreal, yet real.” And Welles replied that he was actually trying to make something that was “unreal, but true.” That, he said, is the highest and best kind of “theatricality.”

What do you think of that? I’ve always said that great fiction is not a depiction of reality. It is a stylized version of reality for a desired effect. And that desired effect is the truth as seen by the writer.

So let’s have at it: What do you think Welles is saying here, and do you agree?

“Truth” is not limited to literal historical “facts.” Whether Shakespeare got the “facts” about Julius Caesar right is not relevant. The truth that the Old Testament presents does not depend on whether the story of Noah’s Ark is literal, historical “fact” or whether the six-day account of creation is literal, historical “fact.” Important truths are conveyed in a different manner by art and myth and legend.

There’s a place for literal, historical fact. We need to know the truth about current events, not some version distorted for propaganda purposes. We can’t settle for “alternative facts” or “creative non-fiction.” But art and journalism are separate undertakings and serve different purposes. Likewise, art and scholarship/science.

I can still picture Professor Wiersma in rapture over Marianne Moore’s great line about “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.”

It’s definitely the “truth” about human nature, and evil, that Welles had in mind, rather than mere facts, which are dull, dramatically.

I think the actor gives the audience what he or she thinks they want or expect. The actor can do that and still be depicting the truth. The absolute truth can be boring as the person doing the thing in real life doesn’t feel they need to do it a certain way. They don’t have an audience. They most likely don’t want an audience. —- Suzanne

Welles the actor was so much “bigger” (not in girth, but in personal magnetism) that every performance of his was outsized. He’s in The Third Man for mere minutes, yet he dominates the film.

I’ve seen him on TV and don’t doubt it. He was one of a kind. 🙂 — Suzanne

great fiction is not a depiction of reality. It is a stylized version of reality for a desired effect. And that desired effect is the truth as seen by the writer.

Love that, Jim. 100% agree. Hope you had a nice holiday!

Thanks, Sue. I look forward to being able to go to the beach next week.

Thought provoking. I watched the entire interview with Welles. He said, later in the interview, “Everyone has his reason.” – referring to Quinlan (? spelling), the rogue cop in the movie.

Reminded me of Mike Romeo. I finished Romeo’s Stand last night. Loved it. Had to finish reading so I could get some sleep. You’re onto something in the plot that is truth, and will be obvious in the future when everyone looks back and says, “What happened? How did we get ripped off?”

Thanks, Steve, for the kind words re: Romeo.

You touched on something that reveals another aspect of Welles’s genius– his ability to see multiple layers of a character. Not pure evil, not pure good. That’s why his performance as Charles Foster Kane is so magnificent. And Quinlan.

Wow! Enjoyed that interview. I plan to go back and watch a few more. Welles is such a genius, he makes an interview a theatrical experience.

“Unreal, but true”. New, but old concept for me. It’s probably been lurking under the surface of my subconscious, waiting for some kind of explanation to come along. And here, you’ve given it to me!

It seems to me that Mr. Welles is saying that truth must be illustrated, painted, sung, or written in a language that I can absorb into a place within me that mere facts would die if left to themselves. I think in pictures. I’m pretty sure most humans do. I need to be shown the truth, not just told the truth.

My WIP, “No Tomorrows”, IMHO, fits this. Ben Franklin once said, “One today is worth two tomorrows”, which perfectly illustrates the theme of the novel.

The story follows the MC, Annie Lee, who comes to believe tomorrow is the day she will die. She has 24 hours to figure out what to do with today, and that 24 hours is rife with what she believes are warning signs. Unreal.

But, tomorrow might be the day she will die. True.

I can’t tell you how deeply I’ve thought about this theme for myself since I met Annie Lee. The images of what she experiences in that 24 hours will stay with me, I think, long after the story is on the shelves, and right up until my last 24 hours.

It’s one of those stories I can’t not write. 🙂

BTW: Can anyone tell me how to use the control key here on TKZ for keyboard shortcuts. When I try to italicize, highlight and click CTRL i, I get an information screen and permissions for TKZ! What am I doing wrong? Many thanks.

Deb, the comments are in HTML The tags for italics, bold and others can be found here:

http://www.simplehtmlguide.com/cheatsheet.php

In the era of film making you’re talking about, I don’t think the question of truth vs fact had ever been the problem for writers. It’s been the problem of motion picture moguls and executives who didn’t understand story.

I have said here previously that I took a course in screenplay writing at a major university in 1974. The instructor–he was not yet a professor of any tier–was an olde tyme Hollywood TV writer, with credits that ran in the field during the Golden Ave of Television. Riverboat, Alcoa Theater, Lux Playhouse, Have Gun Will Travel, Dr. Kildare, and others displayed his and his wife’s works.

But for $28 a credit hour, we spent the entire semester talking about Hollywood STORIES. Not STORY: his dropping off scripts on the doorsteps of his agent and various producers and directors at 3 a.m. because he was running late on his deadlines; a well-known director with a well-known live-in girlfriend who flew him to Los Angeles after he had left to discuss a screenplay but would only pay him $10,000 instead of the $20,000 he wanted (he didn’t get the project). So many stories. So much hilarity. I didn’t learn a thing about screenwriting.

But I realized years later, we didn’t learn anything about screenplay STORY because NOBODY knew anything about it. William Goldman told us that in his great 1983 book, Adventures in the Screen Trade. “Nobody,” he insisted, “knows anything about Hollywood.” Syd Field had validated his statement because Mr. Field wrote his book on screenplay writing that was released in 1979. Mr. Field’s book was a revelation to me. After studying a whole semester in a class on screenwriting, I discovered six years later that screenwriting actually had a structure. (Initially, neither did Mr. Field. One of his first mentors in the industry told him that “something happens about page 60.”) Today, we know and call that happening the midpoint. Mr. Field called it “something” because apparently no one else knew what to call it. The understanding of structure in storytelling is still developing. (I feel inadequate saying this to the writing teacher who discovered the mirror scene.)

So, I think, the problem that Mr. Welles had was not that he couldn’t tell a story. It’s that the executives and moguls in the industry didn’t know what a story–or truth–was. All of the great screenwriting of the 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s was written by writers for folks who didn’t know what they were doing.

There’s a Warner Brothers cartoon in which Daffy Duck is a movie producer. He sits through the screening of his movie. At the end of the showing, he jumps up, screaming, “It’s great, it’s fantastic, it’s marvelous.” Then he four-walls the cartoon audience. “And it’s good, too.” So Daffy had two movies: the one that was great and fantastic. And the one that was good. He saw the one that he could sell to the execs who could sell it to the theater owners, and he saw the one that people would like and lineup to buy both tickets and popcorn to see it.

So Mr. Welles’ problems don’t seem to me to be his. He was working in an industry where money and good looks were the rules of thumb.

When Mr. Welles wrote truth, he was working for guys who didn’t understand what they had. They were too (insert your own adjective here) to understand that a great motion picture–perhaps the greatest picture ever made–was merely, in their understanding, terrific. They didn’t seem to understand the depth and meaning of Rosebud. I’m thinking that, like Daffy, they thought that if they ended the movie on Rosebud, that subtext alone would lend the mystique that would drive ticket sales to make them happy, and enough popcorn sales to make the theater owners happy.

He was writing truth for guys who didn’t know what they were doing. That he did is a great credit to him. But the motion picture industry who thought that squeezing a car horn bulb to make the wonka-wonka sound was a part of great storytelling, didn’t get him or his work.

So, to end, I quote you, Mr. Bell: “I’ve always said that great fiction is not a depiction of reality. It is a stylized version of reality for a desired effect. And that desired effect is the truth as seen by the writer.”

Well said throughout, Jim. Syd Field was my guide to structure, too. I watched a solid year of movies with his “template” before me, noting the times of the plot points. His first plot point I couldn’t quite get. He said it spun the action around. But anything can do that. Finally I discovered that the “spin” was what forced the protag into Act 2. That’s why I started calling it a “doorway of no return.” Structure really started to kick in.

I agree the artist’s job is to convey some kernel of truth to the audience. IMHO, the particular story may be unreal, but the meaning lies within the telling of it.

I watched the interviews of Heston and Welles about Touch of Evil. The opening scene was awesome. I had never heard of the film, but it will be my next treadmill feature!

The Third Man is one of my favorite films. It has just about everything you could want in a story.

Kay, you’re in for a treat.

As for The Third Man, here is yet another example of the Welles genius. The ferris wheel scene has a famous speech about bloodshed and war leading to Michelangelo, etc. That was from Welles. It elevates that scene enormously.

Hi Jim,

I agree, Touch of Evil was a masterpiece, written and directed by a cinematic genius. A few years ago, one of my library colleagues, who was a huge movie buff, learned I hadn’t seen it and highly recommended it. He didn’t steer me wrong. I was only sorry it took me that long to finally see this noir classic.

I think what Welles meant when he said he was trying to create a film that was “unreal but true,” was true in the most powerful sense of the word–emotional truth. Quinlan is unreal but emotionally true in his evil and in the way he behaves. The same is true for the other characters. Fiction may be lies but it must possess emotional truth that resonates with the reader or the viewer. At least, that’s what it means for me 🙂

That was a great question. Thank you! Have a great Sunday!

Exactly, Dale. Emotional truth. So much more powerful than facts!

“The only difference between reality and fiction is that fiction needs to be credible.” Mark Twain

“The difference between fiction and reality? Fiction has to make sense.” Tom Clancy

“A writer uses her own vision of the universe to create her fiction. That vision is ordered so that the complex chaos of reality makes sense and has a pattern.” Marilynn Byerly

Three money quotes, Marilynn. Thanks.

For those interested in Welles, find Dick Cavet’s interview with Welles. He also did an excellent interview with Hitchcock.

“The only difference between reality and fiction is that fiction needs to be credible.” Mark Twain

…

Marilynn’s reply hits dead on what came to my mind immediately after reading Jim’s conclusion, “It is a stylized version of reality for a desired effect.”

…

I’ve always exclaimed/complained that I cannot “get away” with writing reality. Whether it be atrocity or fantastical, there are things that happen in reality that no-one can explain. Things so ridiculous that, even in fiction, I would be lambasted by readers as “beyond the bounds of believability.” As said, fiction needs to be credible.

So I write historical (alternate reality) fantasy. And I still try to keep certain things “believable” but with just enough fantastical to keep the readers interested. Feels a bit like tightrope walking. Haha.

Thanks for the question on italics & bold, Deb! And the html link answer, Jim! I’ve often wondered about that. Hope my attempt worked.

Also need to go watch Touch of Evil now. Sounds amazing!

Very nice italics there, Cyn. Welcome to HTML.

And here’s to writing on a tightrope!

Hey, Jim! I have never won a techie award…*sigh*…the instructions for HTML/italics, bold, underlining were all Greek to me. Couldn’t figure it out. If you, or anyone, has time, could you walk me through it?

Many thanks!