by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

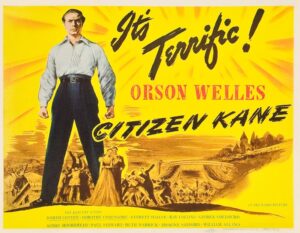

I love Orson Welles. He is one of the few authentic geniuses America has produced in theater and film. At the tender age of 25 he co-wrote and directed what many critics (and your humble scribe) consider the greatest film ever made, Citizen Kane (1941). It was so far ahead of its time that RKO didn’t know how to market it. So they came up with what may be the worst ad line in the history of movies: It’s Terrific!

The movie itself is so good it’s sometimes easy to forget that Welles’s portrayal of the titular character is also one of the great acting performances ever. The guy, in brief, was an amazing talent. Sadly, the studios didn’t get what he was doing and he would have nothing but trouble making films the rest of his life. Still, whenever he did complete a project, it was either a masterpiece or had scenes in it that are unforgettable.

Masterpiece definitely describes Touch of Evil (1958). It was considered by Universal to be a nice little crime movie for Charlton Heston (pre-Ben Hur). No one thought of the material as anything earth shattering. It was based on the novel Badge of Evil by “Whit Masterson,” the pseudonym of crime fiction duo Bob Wade and H. Bill Miller.

Welles was cast as the villain, corrupt police captain Hank Quinlan. This is when the merciful fates of film stepped in. During a phone call between Heston and the producers, Heston suggested that Welles might also direct. Universal asked Welles if he’d like to helm the picture, and Welles said yes, provided he got to re-write the script. Again, considering Welles’s reputation at the time, that Universal acceded to the request makes it seem those movie fates were working overtime.

Touch of Evil, it can be argued, is the last true film noir. But it is so much more. It has the Welles touch all the way through, from the fantastic one-take opening sequence to the shadows and angles Welles did better than anyone. He saw stunning visuals in his prodigious mind and then used whatever camera techniques were available to put them onscreen.

No other director has ever had that singular, Welles imagination.

Then, for some reason, the fates took a coffee break. During the shooting, the studio had seemed very happy with the dailies. But when the rough cut was delivered the honchos got cold feet. Welles was never told why. I suspect that, once again, he was so far ahead of every other filmmaker the studio didn’t how to market the thing. So they took the film away from Welles and did some cutting and re-shooting. Then they ended up releasing it as the B picture on a double bill, with absolutely no advertising. The movie died, and with it any chance that Welles would ever work unhindered in Hollywood again.

But in Europe, especially France, the film was hailed as a triumph. In the 1970s that assessment got to America and now everyone knows it’s a classic.

Throughout his troubled Hollywood existence, Welles somehow kept his youthful ebullience whenever he was interviewed. I encourage you to go on YouTube and search for Welles interviews. They are always smart, funny, charming. Here is one where he talks about Touch of Evil.

In this interview he says something fascinating. Someone remarked to him that Touch of Evil seemed “unreal, yet real.” And Welles replied that he was actually trying to make something that was “unreal, but true.” That, he said, is the highest and best kind of “theatricality.”

What do you think of that? I’ve always said that great fiction is not a depiction of reality. It is a stylized version of reality for a desired effect. And that desired effect is the truth as seen by the writer.

So let’s have at it: What do you think Welles is saying here, and do you agree?