by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I have a good friend who’s a college English prof. He’s an expert in American Lit, with a specialization in Thomas Wolfe. I made some attempts to read Wolfe back in college, but quickly got over it in favor of his contemporary, Ernest Hemingway, and one of his heirs, Jack Kerouac.

But I’ve long had it in my mind to give Wolfe another try. What stopped me was the steep decline in his literary reputation over the past fifty years or so. No less a literary light than Harold Bloom considers Wolfe a “mediocre” talent who has no (as in zero, zilch) “literary merit.”

Now there is a major motion picture out about Wolfe and his editor, the legendary Maxwell Perkins. The movie (which I have not seen yet) is called Genius, based on A. Scott Berg’s award-winning book about Perkins.

So it seemed like a good time to break out my old copy of Look Homeward, Angel and try again. Almost immediately I got frustrated. There is a lot of prose (Wolfe once admitted that his great fault was “too-muchness.”) that is mostly narrative summary. I knew this was supposed to be a novel about a boy named Eugene Gant. But I was not picking up any reason to care about Eugene, the Gants, or the town of Altamont where everything takes place.

After about 150 pages I sent an email to my friend, asking him what I was missing. He sent me a paper he’d done for a conference on how we should approach Wolfe. Wolfe was not interested in writing a traditional novel with an identifiable plotline, my friend explained. Wolfe was, rather, writing to immerse us in a world. He wants us to live there, experience moments and settings. He wants us to feel life deeply even through mundane details.

Okay, that helped. I’m fine with experimental fiction. But in the nitty-gritty of Wolfe’s words I often stumble and grab the dictionary for support. Here, for example, is a clip from a section where Eugene Gant wakes up in the morning and gets dressed:

With sharp whetted hunger he thought of breakfast. He threw the sheet back cleanly, swung in an orbit to a sitting position and put his white somewhat phthisic feet on the floor. Standing up tenderly, he walked over to his leather rocker and put on a pair of clean white-footed socks. Then he pulled his nightgown over his head, looking for a moment in the dresser mirror at his great boned structure, the long stringy muscles of his arms, and his flat-meated hairy chest. His stomach sagged paunchily. He thrust his white flaccid calves quickly through the shrunken legs of a union suit, stretched it out elasticly with a comfortable widening of his shoulders and buttoned it. Then he stepped into his roomy sculpturally heavy trousers and drew on his soft-leathered laceless shoes….

I found myself talking to Wolfe. “C’mon, Tom, really? Phthisic feet? WHAT DOES THAT EVEN MEAN?”

I looked up phthisic. It means a “wasting disease” like tuberculosis.

“Tom! Are you telling me Eugene’s feet had a lung disease? Can feet even look tubercular? Why are you making me stop to think about all this?”

A few pages later Wolfe writes about nacreous pearl light. Back to the dictionary! And guess what? Nacreous means pearly. So it’s not just a ten-dollar word, but I think Wolfe used it redundantly.

And then there are times when Wolfe pops in with author intrusion. To be fair, that’s part of his experiment. But we have things like this: The seed of our destruction will blossom in the desert, the alexin of our cure grows by a mountain rock, and our lives are haunted by a Georgia slattern because a London cut-purse went unhung.

Back to the dictionary! Alexin? (n., a defensive substance capable of destroying bacteria.)

Slattern? (n., an untidy, slovenly woman; a slut.)

But then … what does that passage even mean?

One more: Eugene got back his heart. He got it back fiercely and carelessly, with an eldritch wildness.

Good thing I had the dictionary right next to me! Eldritch, adj., weird; eerie.

Come on, Tom! Why do you do this? Why do you slatternly drive the alexin of phthisic prose eldritchly before my white-footed socks?

Yet in deference to my friend, I’m going to darn well finish Look Homeward, Angel. But I have to say it ain’t easy.

Does that mean I only prefer books with stripped-down style?

Far from it. I do want some style, some voice. But I want it the way John D. MacDonald described it: unobtrusive poetry.

It’s sort of like actors. I’ll confess: I’ve never been a big fan of Laurence Olivier. I always feel like I’m watching an actor working a bit too hard. I admire the craft, but I see the craft. I never feel that way about, say, Robert Mitchum. Mitchum’s performances always look easy. Which is why he is often underrated as an actor.

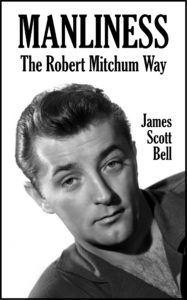

Mitchum actually had a terrific range. He could be cool (Out of the Past), vulnerable (Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison), menacing (The Night of the Hunter), scary (Cape Fear), funny (What a Way to Go). He could be a man of the West (El Dorado), a man of the cloth (5 Card Stud), or a man after a girl’s heart (Holiday Affair). [Also, I find that Mitchum movies have a great deal to say about true manliness, lessons we need to recover. So much do I believe this that I wrote a little book, Manliness: The Robert Mitchum Way.]

How does all this translate to your writing?

- Don’t use a word that a majority of readers will have to look up. Get the story to your audience without needless obstacles, like phthisic feet.

- Major in the voice “formula” of character + author + craft. See my post on that subject here.

- A heightened style is fine if we don’t stop to stop and try to figure out what you mean. I like high style and even lyricism – when it works. For instance, in Ken Kesey’s Sometimes a Great Notion. It’s Wolfeian in heft and experimental in style, yet it doesn’t require a dictionary. And it has a plot!

- It’s okay to overwrite when you draft. That’s often how you get the right touch of emotion and deepen a character. Write like you’re in love.

- But cut mercilessly to make the final product accessible to the reader. This is where you buckle your tool belt and get down to the real work. Edit like you’re in charge.

Now, I don’t want to leave poor Thomas Wolfe hanging out there with Harold Bloom sauce all over him. The guy was in love with writing. It was his life. I can’t deny his passion. So I’ll give him a fair hearing. But when I’m done with Look Homeward, Angel I have a feeling I’ll want to crack open a Travis McGee.

So are there books out there you’ve tried to like, but can’t? You don’t have to name names **COUGH**Middlemarch**COUGH**, but tell us why the book didn’t work for you.

Having lived for a number of years in beautiful Asheville, NC where Wolfe was born, I have always heard a lot about him. However, I’ve never read his work. He is on my list of authors to give a try, but based on the above passage, I, too, would find it a difficult slog.

But the good news is, authors who heavily use ten dollar words don’t always ruin their over all effect. While it is non-fiction, not fiction, I am reading Hampton Sides’ “Blood & Thunder” about Kit Carson and the settling of the American west and this author is quite fond of throwing in ten dollar words here and there. You’re better than me because you bother to look them up, which I don’t.

HOWEVER, Hampton Sides has a riveting style. While the above sample passage from Wolfe is slow and agonizing & I envision it taking months to slog all the way through, Hampton Sides’ 500 or so page work reads very quickly and it’s hard to put the book down.

Ten dollar words aside, the difference between the two is that while Wolfe may have wanted to immerse us in his world, even the non-ten dollar words in the above passage don’t allow me entrance to that world–his over-use of description (can’t believe I’m saying that because I probably like description more than most) makes me want to go take a nap. Hampton Sides, however, provides tons of detail about the people and the world he writes about and he does it while sweeping me smoothly in as if I am really there, living it at the time. Reading that book literally makes me excited to read more.

So even a ten dollar word is forgivable when wielded by the right author.

BK, I do think there’s a difference between fiction and non-fiction in this regard. The latter is more about conveying information. Thus, I don’t mind it so much in NF, if–and this is the big one–the rest of the paragraph is such that the meaning of a “ten-dollar word” is implied. You can “guess” at the meaning and move on.

My problem with the Wolfe passages is that every word is there to create an effect, and I’m brought out of the effect because I’m not sure what the word is there for or, sometimes, what the passage itself means.

I’ve not read Hampton Sides, but I’ll bet part of his allure is that he makes history read like a story. I may have to check him out.

“Why are you making me stop to think about all this?”

Exactly. I want to get lost in the story. And even if I know the meaning (I know slattern), those ten-dollar words jump right out at you. And if you do use one, *please* watch out for repeats. A favorite author of my used “halcyon” at least half a dozen times in her novel, and it didn’t seem to be a word her characters used.

Those ten-dollar words should appear maybe once in the book, unless it’s clear that it’s a character’s favorite. I used “miasma” once, and an early reader, a best-selling author in her own right said she didn’t know what it meant, and she had the English Major credentials. So I cut it, even though I figure with my limited vocabulary, if I know what a word means, my readers should, too.

One character in my new series loves “ten-dollar” words, but he’s a cowboy, and relative to Wolfe’s words, they’re probably only worth a quarter. For example:

***Our guess is those animals ingested something they shouldn’t have, but the vet can’t rule out a parasitic infection.”

Ingested? Not ate? Derek was into ten-dollar word mode, which meant he was upset. And rightly so.***

And right now, I’m being pulled out of a best-selling, award winning author’s book because she’s using “chunky” to describe everything from watches to purses. I plan to run a count once I finish (ebooks are great for that!)

Terry, you bring up a couple of good points. First, if the use of a fancy word is part of a character’s way of speaking, then by all means use it. You even have the other character think about it, so it’s part of the story itself. So dialogue is one place where such words can be used for effect (I keep thinking of the George Clooney character in O Brother, Where Art Thou? He uses highfalutin language to try to appear smarter than he is.

Your other point is one that all writers need to be aware of, the overuse of a word. It happens to me all the time, and my wife catches it. In each book, it seems, I latch onto a word (without being conscious of it) and it keeps showing up. And it’s different with each book!

Those repeated words sure do multiply like cockroaches, don’t they. I run my manuscripts through SmartEdit which helps me find those ‘surprises.’

I appreciate your summary, “The guy was in love with writing.” And I wondered about the origin of: “…our lives are haunted by a Georgia slattern because a London cut-purse went unhung.” I imagined a woman whose criminal ancestors immigrated (after one too many close calls with the law) to the American South, and she was carrying on the family tradition when Wolfe came along. My theory is that his brief, passionate encounter with that Georgia girl became a part of a sentence, the author’s fingerprint in passing. We all leave bits of our DNA in our writing, don’t we?

Tawn, in the rest of that passage I think I have an idea of what Wolfe was getting at. The passage is about chance and fate, and how things change it. The unhung cut-purse is like the “butterfly effect” in that regard. It took me some detective work to formulate that theory, though.

If that passage had been put into Eugene’s head, in Eugene’s own language, as he’s struggling with the thought, feeling the despair of it, how much more effective it would have been.

And some books I tried to like (because they were book club selections):

Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

Cuba Libre

The Falls

The Art of Fielding

… and numerous others, but I don’t want to mention books by authors who might read this blog, or who know me, or who aren’t the ‘big names’ who have huge readers.

And that should be “readership” or “a huge number of readers.” Sorry. Small people are allowed to be readers, too.

“I’m brought out of the effect because I’m not sure what the word is there for” yes! There are so many adjectives and adverbs they get in the way of visualising this man who has big bones but everything else is stringy, flat-meated, sagging and flacid. How does he stand up tenderly? Did he sit in the leather armchair to put on those strange socks (I imagine white feet and an unnamed color for the rest)? If he did sit, how could he see himself in the dresser mirror?

I was also brought up short wondering how someone could get his heart back both fiercely AND carelessly. The two words do not seem apposite (hey, there’s a good word to look up!)

BTW, there’s a famous article (still up) called “A Reader’s Manifesto” which took to task some leading contemporary writers on the same grounds:

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2001/07/a-readers-manifesto/302270/

Thanks for the link to an excellent article, although it wasn’t fun watching two of my (maybe formerly) favorite authors get torn to bits. Ouch! I’ll Have to take another look at Cormac McCarthy and Annie Proulx and also read some of the writers he suggests.

Jim,

Great points. It’s interesting that, according to your friend, Wolfe’s goal was to “immerse” us in the world of his protagonist. Yet, by his narrative style, he does the very opposite.

TINKER, TAILOR, SOLDIER, SPY is the book I’ve failed to “conquer” after two attempts. Le Carre’s dialogue is so full of idioms that I just didn’t understand what was being said. If you have any clues on how to approach his writing, I’d love to hear it.

Thanks for your post.

Steve, I think the best approach to Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy is to watch the mini-series starring Alec Guinness. Some of the best TV ever.

Come to think of it, that would make a good post someday. Movies that are better than the books.

I’m with Terry Odell re: Girl with Dragon Tattoo. Tedious and preachy.

Give me Mickey Spillane, Robert E. Howard, Ernest Hemingway.

I like your choices, Mike.

And speaking of movies better than the book, I found the Swedish movie version of Dragon Tattoo superior.

I just bought your book Masculinity. Looking forward to reading it!

My thanks. Enjoy!

I take it you were never a fan of My Word! I’m of two minds on the usage of so-called ten dollar words. If a word is going to take the majority of your readers out of the story then don’t use it. Be spare. OTOH sometimes ten dollar words are so descriptive and specific and perfect for a situation that it’s hard not to use them if you know them. Granted, I have yet to find the right text to slip pogonotomy into, but still. And I love slattern/ly. It’s got just this delicious little connotation to it that doesn’t necessarily mean slut, that is almost more class oriented. You would never use it to describe Carrie Bradshaw and company going out to a bar in NYC, but you might use it to describe a different group of women, notably working class and dressed in spandex from the 80s, revealing outdated tops, and with big hair, going out to a bar in, say, a depressed mining town. I’ve used it in conversation, but not writing. I would, though, in the right context. (If only there were an equivalent word for men.)

When I was in my teens/early 20s I read a lot of books, many older and literary – and would keep a running list of words I didn’t know and look them up daily. I enjoyed that so much I would even go to the library and randomly pull a volume of the OED – the full length multi-volume, not the condensed – and go through it randomly, looking up words I’d never heard of. I especially loved the etymology the OED provided, something no other dictionary does as well. I do love a well-placed, specific “ten dollar word”. Maybe I just have a higher tolerance for obscure words than the average person.

I am a word lover, too, Cat. I did the same thing you did. I’m just afraid we’re in the minority among fiction readers.

Still, if you want to spend ten bucks on a word now and again, fine. I just think Wolfe overspent.

There are highly educated readers who appreciate good words and enjoy it when philosophers like Kierkegaard are mentioned in books. I say let the skillful thunder rumble, but don’t be pretentious. When you write, be yourself.

I “hear” the words in my head when I read, and I can’t pronounce “phthisic feet.” I don’t have to know every word on the page — I like a challenge — but Thomas Wolfe reads like someone who is deliberately trying to be literary. A far better example of literary writing is Tom Wolfe. His fiction and non-fiction, including the “The Right Stuff,” and “The Bonfire of the Vanities” are literary in the best sense of the word. And he enlightens us about two very different cultures.

Thanks for mentioning Tom Wolfe, Elaine. He is one of my favorite novelists. His style is funny and high-flying and the sound of it makes crazy sense.

I think if you imagine a cat spitting, you might come close on “phthisic”.

It’s been a long time since I put down a book because of comprehension issues/boredom, but I think Wolfe takes the cake. This from the person who quite cheerfully read all of Dickens’s Bleak House and would like to read it again. The last book I had real trouble understanding was Bob Son of Battle because of the Scottish accents. That book is profound, man. They should teach it in colleges.

I’m afraid that most “literary” fiction I read was the pulp of its time. Nicholson Meredith is such fun–love those thriller mysteries.

Dickens had plot, plot, plot. And character, character, character. Long, yes, but page-turning!

I bounced on Steinbeck and East of Eden. The man knew and loved his words – and used them all.

Bounced on Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (but stole the rhythm for my tag line.)

Prefer Hemingway and Fitzgerald for my classics. McLean, Fleming, Ludlum, Follett, and Forsyth for thrillers. All could tell a story.

Good choices all, Paul. Tell me a story!

It’s not really fair to compare an author who wrote many years ago to a totally different audience to current writers. Wolfe wrote mainstream literary fiction, not popular genre, and narrative style has changed so drastically it’s bare bones in comparison.

Wolfe was so verbose that Maxwell Perkins’ primary job with him was to hack out a hill novel out of an Everest of prose.

I do think Wolfe was experimental even for his day. Not as much as Gertrude Stein, of course, who no one reads. Hemingway was going in the opposite direction. Fitzgerald seems right in the middle. Wolfe and Fitzgerald exchanged a couple of snarky letters over Wolfe’s style.

I stumble on many of the classics. I don’t mind running to the dictionary every now and then as long as it adds meaning. I stumble on long reams of description. It’s just me, I know that. I liked Steinbeck’s The Pearl, and loved Jekyll and Hyde (now there’s a book that requires a dictionary!). Liked Silas Marner and anything by C.S. Lewis. Hemmingway, Dickens, almost anything Bronte or Austen (I know I know – everybody loves them) just kill me. Get to the story already!

I loved LOTR, but skipped pages of internal dialogue that seemed extraneous. I’m reading the Outlander series right now and have fallen in love with the characters, which is a good thing because I skip pages of descriptions of what’s in the pantry or growing by the side of the river. Don’t care. lol

Elmore Leonard said he tried to write the parts people skip. Ha!

Not all of Wolfe’s prose is horrid. Here’s a quote I like to pull out when I try to explain Southerners’ love of snow.

“Snow in the South is wonderful. It has a kind of magic and mystery that it has nowhere else. And the reason for this is that it comes to people in the South not as the grim, unyielding tenant of Winter’s keep, but as a strange and wild visitor from the secret North.”

Yes, I agree. I would not call Wolfe “horrid.” He had obvious talent. Unrestrained talent …

Brad Thor.

The guy is in love with the word “had”. In one of his books I counted 16 in one and a half pages, and then threw the hardcover in the trash. I just read an excerpt from his latest work and “had” was scattershot all over the page, so I passed on the purchase.

Obviously the guy can tell a story, but the quality of his writing is extremely poor.

Oh, yes.”Had” is so often overused, even by vets. Use ONE to get into past tense, then unnecessary.

I don’t get why poorly written work makes it to market. I suppose once a level of market success is reached the quality of a work invariably suffers as creating art is no longer the objective, but rather cashing in on a cash cow becomes the primary focus.

It’s not about a beautifully told and well written story that provides insight into our own humanity, no, it’s about selling unpolished, vapid television in print form, what Robert Mckee called “entertainment with a small e”. Sigh. I threw the tv in the dumpster back in 2009.

I take an immense pride in my work and I’d never sacrifice that for a big payday. I’d rather work a crappy part-time job than work full time for a major publisher if it meant maintaining the integrity of my work.

And so I’ve recently given up my dream of working as an author for a major publisher, not only because the quality of my work is important to me, but because of the subject matter I engage. Put simply, it goes against the dominant narrative and zeitgeist of our time.

Apropos: Sol Stein said that it takes guts to be a writer. And he’s exactly right.

With a Master’s Degree in Literature, I have just suffered again from someone pushing my guilt button. Only because my advisor has passed on can I confess that I could not get through LOOK HOMEWARD. Yet I have recommended this film to every writer I know. Hearing Colin Firth read the opening was magnificent. A whole world unfolded in that paragraph. I wish I could do that. Yet I know, if I did, no one would read me.

Even the paragraph you offered had me wanting to skim after about 5 lines. But you can’t speed read Wolfe. So I respect you for your persistence; let me know how it all came out. (Wolfe probably uses semicolons, right?)

Here’s my favorite line from the film, spoken by the editor:

Did I make his writing better or just did I just change it?

(Maybe not verbatim, but the gist is there.) I wonder how many editors have these thoughts.

I have three considerations regarding author word use:

1) what is the expectation of the reader? I expect to have to look up words with T. S. Eliot. The real joy comes when I don’t have to look up those esoteric words.

2. is it the author speaking or a character? If the character would really use those words, then use them. I won’t mind looking up words that hedge fund managers use in conversation. If it is the author speaking then don’t use them. I’m not that interested in words the author knows.

3. Is the odd word understandable from the context? If the context gives away the meaning of the word, that’s fine. That’s how I first acquired a lot of my vocabulary. If the word is not understandable from the context (and it was not part of character dialogue), then don’t use it.

As for a writer I’ve never been able to finish reading any of his books: Thomas Hardy. But then I just might not like naturalism.

Vince