by Matt Richtel

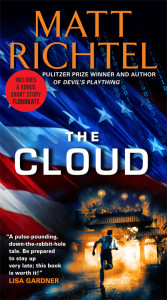

TKZ is once again delighted to host Pulitzer prize-winning author Matt Richtel. His latest release, THE CLOUD, just hit bookstores, and I can personally highly recommend it!

This true story ends with me sobbing. In public.

The story starts five weeks ago, on a Monday night, with a text. I was amid an exciting time, working on a front-page story for the New York Times (my day job) about a controversial new twist involving computers and schools, and I was preparing for the Jan. 29 release of my new thriller, The Cloud.

The story starts five weeks ago, on a Monday night, with a text. I was amid an exciting time, working on a front-page story for the New York Times (my day job) about a controversial new twist involving computers and schools, and I was preparing for the Jan. 29 release of my new thriller, The Cloud. The text came at 8.06 p.m. It read: “Call me.”

The text was from Adam, a good friend of mine and editor at The New York Times. About a year earlier Adam had been put in charge of a group of eight, mostly veteran reporters, including me. The group was called “How We Live,” and its charge was to make a journalistic beat of the way people live their lives; how we eat, sleep, learn, fight, procreate, and how we die.

We were supposed to be a new generation of newspaper story tellers – part of an overall move in the newsroom to infuse stories with narrative, voice, and character. The days of authoritative top-down explanations in the New York Times were increasingly giving way to showing and not telling, and sophisticated story telling, appealing to heart not just head.

We were responding to the need to capture and keep reader attention amid the white digital noise of an Angry Bird world.

In response to Adam’s text, I called him. Before I tell you the shocking news he told me, please indulge some additional, necessary, backstory.

Over the last year, my fiction career was also evolving to suit the digital world. Like many thriller-writing peers. I was writing more and more, adding to the already heavy book-a-year-load.

In August, I published a short story, Floodgate, 15,000 words I hadn’t anticipated writing, aimed at staying in touch with an audience feeding from the all-you-can-tweet-buffet.

And I took hard to Facebook, something initiated as a marketing tactic, but that transformed also into a usually welcome labor, in which I write stuff my toddlers say (funnier than I could ever make up) and occasionally quip about story telling.

I amassed some 20,000 Facebook subscribers on my personal page. And several thousand likes on my fan page. We got nice press for Floodgate. Apparent success on all fronts.

I amassed some 20,000 Facebook subscribers on my personal page. And several thousand likes on my fan page. We got nice press for Floodgate. Apparent success on all fronts.The New York Times stuff seemed to be working out too. The How We Live team killed it. Something like 35 front-page stories and 90 stories for the front of our feature sections, like Dining, Home, Travel. We generated a ton of traffic. We were a hit.

Then, fast forward to five weeks ago, I got the text. From Adam, on the Monday night. “Call me.” I called. In a nutshell, he explained, the paper was disbanding the How We Live group. And not just that; the paper was doing a whole bunch of shifting, all over the place. Voluntary buyouts, long-time editors and friends leaving, reorganization.

Why? Stating the obvious: because the paper’s news gathering operation – the news gathering and storytelling operation – cost too much. It was built in a different era, when our costs were supported by print advertising. Remember that old thing?

I’m no stranger to the ups and downs of the changing media landscape. I started and worked my way up from small newspapers, starting in 1990, at which I survived probably half a dozen rounds of layoffs. I know not to let macro-economic forces get me down.

But after I talked to Adam, I went into a tailspin. One that had been a year in the making, at least.

All this hard work. All this adaptation. So much terrible uncertainty. Part of what I experiencing, I am adult enough to know, was the personal uncertainty of the reality I’d need to find a new job inside the paper (I have), and that I was poised to have The Cloud come out (it did, two weeks ago). That meant marketing, travel, speaking, radio, and the subterranean terror that accompanies a book release: will only my family buy it?

But there was something much bigger for me too. I was confronting, squarely, for the first time, the reality that we don’t know what works. We.Do.Not.Know.What.Works.

What has value? How much value? Will we have mere chaos, only chaos, since Jack Dorsey, of Twitter, wrote his infamous missive: “…we came across the word ‘twitter’, and it was just perfect. The definition was ‘a short burst of inconsequential information,’ and ‘chirps from birds’. And that’s exactly what the product was.”

Inconsequential? Only if you’re not competing against it to pay the bills, and satisfy your muse.

My sleep deteriorated. I experienced a very unusual level of anxiety. I couldn’t write. I was a rotten dad. For two weeks, I felt like crud. I couldn’t find steady ground.

Then on a Monday, two weeks after the text, I took myself on a Monday afternoon to see Lincoln. No sooner had the opening music began to swell then I had tears in my eyes. They stayed there, persistently, throughout. And by the time a bereft Sally Fields dropped to her knees during a particularly emotional scene with Daniel Day Lewis, I began sobbing. Just lost it.

I was a mess the rest of the movie.

When I walked out, it was the best I’d felt in weeks. Cleansed.

And it’s when I finally understood the thing that had been eluding me for weeks, maybe for much longer. I finally understood the value of The Story. And of storytelling. And of its place in the digital world.

I’ll tell you first my conclusion, and then explain.

My conclusion: The bad story and story teller has little value, or, at best, ephemeral value; so too the mediocre story and storyteller, and even the merely good ones.

The great story and story teller is more valuable than they have ever been.

They are a port in the storm. A place to pause and heal from all the white noise the world throws at us, a tiny closet to cower inside and rest from the swirl of inconsequential missives.

And, more than that, great stories are the place where we will change the world. In Lincoln, Tony Kushner and Steven Spielberg, two of the greatest story tellers of our age team up to make a movie that is, perhaps above all, an homage to storytelling. They teach us that Lincoln used story-telling, narrative, anecdote, quip and emotion, to deliver the United States from slavery.

I know this doesn’t answer the business-model question. That’s the one that plagues us, still. Will the New York Times face bigger challenges? Yes? Will The Cloud take flight? Not as it might have when the institutions of publishing had more power (It is my most ambitious and mature and entertaining work to date).

But it’s not the business model question I needed an answer to. It was the emotional one, the real one. And I got that answer sitting in a movie theater, sobbing.

Fellow story tellers, take seriously your duty. The world seeks deliverance. You hold its key.

Powerful post, Matt.

I needed it personally. Feeling buffeted and battered, have just started a new book with a new protag that will take me back to that scary place “spec land.”

I needed it professionally. Am leaving tomorrow to teach a writing workshop where, am I sure, everyone wants to be the next E. L. James.

How do I convince them (and maybe myself?) it is still, and always will be, the story?

Well said. Great stories heal, explain, give catharsis.

Although I am not financially dependent on the newspaper business, I am pained by what is happening to my local newspaper and the national papers like NYT. I pray some business genius will figure out how to preserve the crucial role of professional journalists.

P.J. – my take, from Lincoln, use the story to prove the value of the story. tell the students a story. They’ll be so caught up that you’ll have made the point and then you can give ’em the punchline after they’ve been caught. A poor man’s two cents (not that you were necessarily, actually, asking)

Great post Matt – stories can provide the necessary outlet for emotions that we often don’t confront fully in our day to day lives. My English heritage usually makes me keep a stiff upper lip – but in movies and with great books, I feel I can be off the hook and can dissolve into a puddle of tears without any qualms!

Matt, I had a similar reaction to “Lincoln.” Tears started at the top, with the soldier reciting the Gettysburg Address to Lincoln, came and went throughout the movie, swelled to a crescendo when he took that last solo walk down the hallway toward the end, flowed right through the credits. Marvelous. Hopeful.

Great post Matt. I haven’t seen Lincoln but I can identify with some aspects of the rest of your article. IE career change v. job satisfaction. I think this is the crux of what you are talking about here. Being able to live doing what we love, while sometimes seeing work we love wrenched from our grasp, doors closed hard and finding ourselves back to square one the story still pulsing in our hearts, the scroll on which it was forming in blackened tatters at our feet…the stench of smoking digital vellum stinging our eyes.

I am sitting here now with a heavy contemplation on my mind. Telling my own stories through writing is pure pleasure that makes some money for me, but not near enough to live on. Audiobook narration, giving life to other people’s stories, is just as satisfying and makes a greater portion of that living, to the point where it is balancing the day job and could, with a bit more effort it could surpass the day job.

The day job in my case is a relatively solid Federal IT job that is fairly but not insanely busy. Good, solid income but never going to be rich at it. Not likely to get rich in audiobooks and writing, but might do pretty well if all lines up right. The pains you describe above remind me of the risk factor of going back into self-employment (I owned a computer business for many years in the 90s). I might well fail. My youngest kids are teens, not little like the last time I leaped, so the sting of potential defeat won’t be family crushing, but still.

Looking at the market and knowing the way things go in business I am teetering and tottering and wondering if I jump, will I fly? Or will I fall?

Or with fruitlessly stretched pinions like an eaglet fearing to leap from the nest, will I grow old with regret at the memory of flight not taken to wing?

Powerful post.

I lost my job in April of ’09. The money I make with my writing is less than 1% of that annual six figures times four years running. But, I work for myself. No one decides my fate anymore and I like it that way. Truth.

“We.Do.Not.Know.What.Works.”

My question back to you is this: “Do we have to?”

The world is ever changing. There are generations of kids who want for nothing. I just realized the other day that I send my two off to school (high school and middle school) every day with $800 worth of stuff (a piece) in the form of a school-issued laptop and $400 iPhone 5s, while I still remember when the Burn kids got the first colored T.V. in the neighborhood. Ha!

Angry Birds. Twitter. Facebook. Yes, it can be fluff.

Still. Connections matter. Words still matter. Clear thought matters.

All you can do is write true (which you already do) and live true in everything you do (which you must do already). I believe that’s what the film was saying to you.

Powerful stuff, this life.

Thank you for an absolutely beautiful and moving post! I just bought your book based solely on this. Wishing you much success in future endeavors.

Just a note to everyone who wrote in support of the post. Thank you for your thoughtful responses. You’ve all got me thinking about one small addendum. I think the Internet has created a grand illusion. It is this: because we CAN reach so many people (read: everyone on the planet) we somehow sometimes think we SHOULD reach everyone. Time for me to get peaceful again that I (we, each of us) has our audience. And having reached them, and connected, we write our stories and hope to reach again. Thanks all for the feedback and the reminder it prompted. Oh, and Teresa Robeson, thank you for taking a chance on The Cloud. I hope you love it.