“Good ole Fred,” I say.

“Who?” you ask.

“Fred. Fred Mahle. My mentor.”

“Okay,” you go.

“Fred was my police mentor. He was a Detective Sergeant on the homicide squad who must have seen something in me as a rookie and thought I was worthwhile mentoring. Because of Fred, I learned the criminal investigation ropes and managed to make a somewhat successful career out of being a murder cop.”

“Nice,” you say.

“Sadly, Fred’s long gone now. But what he taught me stuck. Fred fed me wisps of wisdom like, ‘God gave you two ears and one mouth for a reason’ and ‘You get more bees with honey than you do with vinegar.’ Fred was a Columbo character with a Da Vinci brain. He was the one who caught child serial killer Clifford Olson and struck the deal to pay Olson ten grand a piece to turn over the bodies. In the end, Olson got a hundred thousand and a life sentence. Ten families got closure.”

Impressive. “What brought this on for a Kill Zone post?”

“I’m doing a bit of mentoring now myself. Not as a detective, but as a writer. I’m a writer who’s mentoring a detective.”

(Laughs) “Say what?”

“Yeah. It’s come full circle. When I retired from being Doctor Death in the police and coroner business, I reinvented myself as a crime writer. Not necessarily a good crime writer, but I’ve learned a few tricks, and I’m in the position to share them with a real detective who’s just retired and wants to take up this crazy wordsmithing game. Get this. She’s silly enough to turn to me for advice, so now I’m mentoring her.”

“Go figger.”

——

I think all of us have been mentored to some degree throughout our lives—careers if you like. And I’d like to think that as we get older and more experienced in our lines, we mentor others. That may be a formal mentorship as in an apprenticing role or an informal one like touring the new hire around the book factory floor.

And I think you learn a lot on both ends—mentor and mentoree (master/protégé). I’ve been commercially writing for a while now and when I put together a “mentorship” program for the poor sucker nice lady I’m helping out, I was surprised to find just how much I’ve learned about the writing craft and biz. I look forward to this journey with her.

And I think you learn a lot on both ends—mentor and mentoree (master/protégé). I’ve been commercially writing for a while now and when I put together a “mentorship” program for the poor sucker nice lady I’m helping out, I was surprised to find just how much I’ve learned about the writing craft and biz. I look forward to this journey with her.

Ever wonder where the word “mentor” came from? No, neither did I until I sat down to rabbit-hole a bit of research for this piece. Here’s the scoop.

Homer, the Greek writer, had a character called Ulysses in his epic work The Odyssey. Ulysses was prepping for the Trojan war and knew he’d be away for a while. (Turned out it was ten years.) So Ulysses entrusted his only son and heir, Telemachus, with being scholared by his wise and learned friend, Mentor. There, you’re welcome.

History shows that people like us—like young trees in an old forest—thrive best when we grow in the presence of those who’ve gone before us. This isn’t new ground. Even the greats like Plato and Aristotle were mentored. Same with Michelangelo and Van Gogh. I’m sure great writers like Hemmingway had some sort of mentor other than a whiskey flask.

I Googled around for mentoring’s best definition and to find some sort of accepted format for a mentorship program. Wikipedia (a mentor of sorts) says: Mentorship is the influence, guidance, or direction given by a mentor to a mentee. A mentor influences the personal and professional growth of a mentee and offers psychological support, career guidance, and role modeling. Mentoring is a process that always involves cross-communication. It’s relationship-based, but its precise definition is elusive.

I found an interesting paper by a mentoring guru. It’s called Skills For Successful Mentoring: Competencies of Outstanding Mentors and Mentorees, and it’s written by Linda Phillips-Jones, Ph.D. She also wrote the book The New Mentors and Protégés.

Dr. Phillips-Jones says that effective mentoring requires more than common sense. Her research indicates that mentors and mentorees who develop and manage successful mentoring partnerships demonstrate specific and identifiable skills that enable learning and positive change to take place. She notes that unless a fairly structured process and specific skills are applied, mediocre relationships occur.

Dr. Phillips-Jones says that effective mentoring requires more than common sense. Her research indicates that mentors and mentorees who develop and manage successful mentoring partnerships demonstrate specific and identifiable skills that enable learning and positive change to take place. She notes that unless a fairly structured process and specific skills are applied, mediocre relationships occur.

The paper offers a mentoring skills model that’s widely used in many businesses, large and small. It’s as close to a mentorship blueprint that’s out there. Here are the four primary or core mentor skills:

Listening Actively — A mentor must know their protégé’s interests and needs. Active listening is the most basic mentoring skill. When an understudy feels they are being heard and understood, they develop trust and this allows the relationship to grow.

Building Trust — The more the student and teacher trust each other, the more committed they’ll be to building their relationship and mutually benefiting from it. Trust develops over time if partners respect confidentiality, spend time together, cooperate constructively, and the mentor offers encouragement.

Determining Goals and Building Capacity — The mentor acts as a role model. They already have the experience required to lead which is done by setting goals and building competencies. Mentors act as resources or find them for their charge, impart knowledge, help with broader perspectives, and inspire the mentoree.

Encouragement — Dr. Phillips-Jones says giving encouragement is the mentoring skill most valued by protégés. She gives encouraging examples like favorably commenting on a mentoree’s accomplishments, communicating belief in the protégé’s growth capacity, and positively responding to inevitable frustrations.

The paper goes on to give practical advice on building a mentorship program. It states like most relationships, mentoring progresses in stages with each stage forming an inherent part of the next. Here are the four stages that frame a modern mentorship program:

Stage I — Building the Relationship

Stage II — Exchanging Information and Setting Goals

Stage III — Working Toward Goals / Deepening the Engagement

Stage IV — Ending the Formal Mentoring Relationship and Planning the Future

Dr. Phillip-Jones’s paper drills deep into developing each stage. It’s far more than a blog post can handle. If you’re interested, the Center for Health and Leadership has another paper titled Mentoring Guide — A Guide for Mentors which you can download for bedtime reading.

My Google trip took me to a place called Masterclass. You might have heard of it. I found a short but sweet post called How to Find and Choose a Writing Mentor. It opens with a cool definition: A writing mentor is an experienced writer who shares their wisdom with a new writer as they begin their career. The mentor provides support through regular meetings, either in person, on the phone, or online. A mentor will help a new author develop their voice and improve their writing skills by reviewing and critiquing their work. The mentor acts as a resource for ongoing support and creative growth.

My Google trip took me to a place called Masterclass. You might have heard of it. I found a short but sweet post called How to Find and Choose a Writing Mentor. It opens with a cool definition: A writing mentor is an experienced writer who shares their wisdom with a new writer as they begin their career. The mentor provides support through regular meetings, either in person, on the phone, or online. A mentor will help a new author develop their voice and improve their writing skills by reviewing and critiquing their work. The mentor acts as a resource for ongoing support and creative growth.

How to Find and Choose a Writing Mentor itemizes six benefits of having a writing mentor. They are:

A mentor holds you accountable.

A mentor inspires you.

A mentor improves your writing skills.

A mentor supports your career path.

A mentor helps develop your voice.

A mentor helps you make decisions about publishing.

Besides the benefits, the post lists four things to look for in a writing mentor. These are:

Experience

Commonality

Accomplishments

Availability

And the article ends with four tips for finding a writing mentor. Here you go:

Find a writing community.

Become a member of a writing organization.

Take classes in person

Find a mentor online.

Do, or did I, have a writing mentor? Of course, I have. My number one inspiration has, is, and always will be Napoleon Hill’s classic works Think and Grow Rich. Some say Napoleon Hill was one big con-job, but say what you like—Think and Grow Rich is magic mentorship at its finest. There’s stuff in there that’ll change your life. Believe me, I know.

Stephen King is also my mentor. Now, I don’t pretend to know Stephen King personally, just as I never knew Napoleon Hill. What I’ve got from Stephen King’s works and his classic On Writing is a lifelong course in the craft. Here’s a post I recently wrote on my personal blog at DyingWords.net which is titled Stephen King’s Surprisingly Simple Secret to Success.

Stephen King is also my mentor. Now, I don’t pretend to know Stephen King personally, just as I never knew Napoleon Hill. What I’ve got from Stephen King’s works and his classic On Writing is a lifelong course in the craft. Here’s a post I recently wrote on my personal blog at DyingWords.net which is titled Stephen King’s Surprisingly Simple Secret to Success.

The Kill Zone is a mentorship in progress. I think that’s the ultimate goal of the Kill Zone — writers sharing their skillsets with other writers. That’s what I try to do around this place. I find it rewarding to help other writers help themselves, and I’m sure most writers feel the same thing. Especially Kill Zone writers.

I want to call out two Kill Zone contributors who act as mentors. One is James Scott Bell, or JSB, who has a lifetime with his butt in the chair and his fingers on the keys. Jim has a wealth of knowledge in his craft books, and his posts always lift me up. That’s mentorship.

The other is Sue Coletta. This totally unselfish gem is somewhat at the same writing career stage as me, and we act as peer mentors. My wife, Rita, calls Sue my “other wife”.

What about you Kill Zoners? Do you have mentors? Have you worked with mentors? Are you now mentoring someone else? And would you mentor someone if given the opportunity? Don’t be shy with your comments!

——

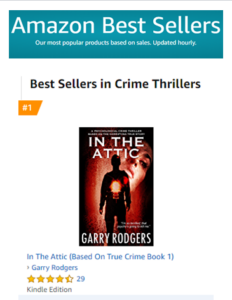

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner. Now, Garry’s a crime writer and indie publisher of sixteen books including an international bestselling based-on-true-crime series.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner. Now, Garry’s a crime writer and indie publisher of sixteen books including an international bestselling based-on-true-crime series.

Outside of writing, Garry Rodgers is a certified marine captain and enjoys time putting around the saltwater near his home on Vancouver Island in Canada’s Pacific Northwest. Follow Garry on Twitter and check out his popular blog at www.DyingWords.net. BTW, In The Attic is FREE on Amazon, Kobo, and Nook.