by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

It used to be the standard advice for new writers: Write what you know!

The driving idea behind that sentiment, of course, was that to write authentically, accurately, and with convincing detail you needed to stick with your own experience, for that is obviously what you know best.

Thus, for many decades, writers kept it close to home. Fitzgerald wrote about the Jazz Age as he was living it with Zelda. Hemingway wrote about World War I and its aftermath, then about other things he experienced—fishing, hunting, the Spanish Civil War. James Jones and Norman Mailer burst on the scene with novels about World War II. Harper Lee wrote about her own childhood.

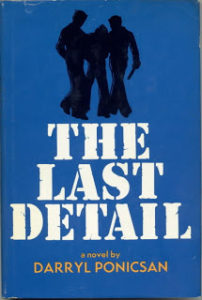

I recall when the movie The Last Detail came out, based on the novel by Darryl Ponicsan. There was a story about Ponicsan in the L.A. Times in which he talked about his decision to join the Navy at the age of 24. He did so because he wanted to expand his experience so he had something to write about.

I was a college student at the time and got a copy of the novel, read it and loved it. So I wrote a “wannabe a writer” letter to Ponicsan, care of his Hollywood agent. Mr. Ponicsan wrote me a nice letter in return, with advice and encouragement and one important caveat. The last line of his letter was, “Be prepared for an apprenticeship of years.” That was 21 years before my first novel came out.

But is Write what you know still sound advice? If you incorporate your special area of expertise in a natural fashion (say, as a lawyer writing legal thrillers), it’s fine. What’s not fine is if it’s taken as Write only what you know. That, it seems to me, destroys one of the great joys of being a writer—the ability to go anywhere, create any character, so long as you do enough research to make it all ring true.

Thus, the better advice, it seems to me, is Write what you WANT to know.

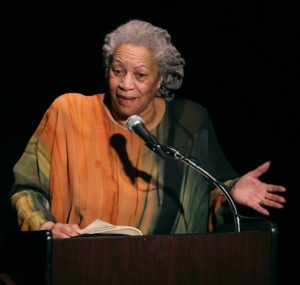

I recently came across a 2014 interview with Toni Morrison in which she said:

I may be wrong about this, but it seems as though so much fiction, particularly that by younger people, is very much about themselves. Love and death and stuff, but my love, my death, my this, my that. Everybody else is a light character in that play.

She continues:

When I taught creative writing at Princeton, [my students] had been told all of their lives to write what they knew. I always began the course by saying, “Don’t pay any attention to that.” First, because you don’t know anything and second, because I don’t want to hear about your true love and your mama and your papa and your friends. Think of somebody you don’t know. What about a Mexican waitress in the Rio Grande who can barely speak English? Or what about a Grande Madame in Paris? Things way outside their camp. Imagine it, create it. Don’t record and editorialize on some event that you’ve already lived through. I was always amazed at how effective that was. They were always out of the box when they were given license to imagine something wholly outside their existence.

What a refreshing counterpoint to sticking to “what you know.” Go outside the camp. Be reckless, be an explorer. Imagine it, then create it. Part of the imagining, of course, involved research.

As I look back on my own writing, I notice that at least half the time I’m writing about a woman protagonist.

How on earth did that happen?

Well, first of all, I find women more fascinating than men. I’m a simple creature. My wife is complex. I count our 37 years of marriage as not only an adventure in love, but also an engagement in a ton of research. Which is why Mrs. B is always the first to read my work. I need to get this stuff right.

When I came up with the concept for the Kit Shannon series, the publisher I pitched it to had the idea of teaming me up with one of its top-selling authors, Tracie Peterson. We got along famously. We brainstormed the plots and I wrote the first drafts. Tracie went over the drafts and tweaked and added more of what a woman would have thought, spoken, noticed. By the time we finished the third book, I felt I had inside me the voice we’d developed together. I was then able to go on and do three more of these novels on my own.

Which may have been the most enjoyable part of my career. I loved living through Kit Shannon, even though I have never been a woman living in 1903 Los Angeles. (Not many of us have, I venture to say.)

So follow Toni Morrison’s advice. Don’t be afraid to go outside your camp. It’s one of the great pleasures of writing fiction.

So what do you think of that old chestnut, Write what you know?