Today, I welcome to TKZ my friend and fellow ITW member, New York Times bestselling author, Tosca Lee. Because of the historical nature of so much of Tosca’s writing, I asked her to share her thoughts on research. Enjoy!

Joe Moore

—————–

I’m asked often how I research my historical novels. I’ve steadfastly avoided writing about this topic until now I think because it’s such a personal process—one dictated by how a  person sorts, digests, and stores information. None of us will do it the same. That said, having had to pack the equivalent of a dissertation’s worth of research into six months on occasions before, I have picked up a few tricks.

person sorts, digests, and stores information. None of us will do it the same. That said, having had to pack the equivalent of a dissertation’s worth of research into six months on occasions before, I have picked up a few tricks.

1) Start pedestrian. Do what everyone else does: Google. Wikipedia. YouTube. See what’s available on Amazon. Read and watch widely.

2) Acquire key references for your library. These are the staple works and experts that books, articles and documentaries about your topic refer to time and again. For the first century, it’s the historian Josephus. For period warfare, Carl Von Clausewitz. Find your staple information.

3) Find specialty outlets. This is where I divert to the History Channel. National Geographic. The Discovery Channel. Coursera. Two of my power tools: The Great Courses and the (in my opinion) less-utilized and under-appreciated iTunes U. These last two, in particular, are rich sources of highly-organized, consumable information by leading experts and ivy-league academics. True, the Great Courses are not cheap. If scrimping, look for the course on eBay, or order only the transcript. iTunes U. is free.

4) Identify your experts—the writers of the staple books (or their commentaries), the leading academics or specialists teaching the lectures or commenting in the documentaries. These may also be area experts or locals living in your setting (travel guides, bloggers and book authors are excellent for this) or doing what they do.

5) Recruit. I never write a novel without at least a small group of experts in my pocket to either point me in the direction of information I need or to directly and expediently answer a question as I’m working. Don’t be afraid to write and introduce yourself and how you came to find them. Be direct with queries and questions, and therefore respectful of their time. Curators of specialized information are eager to help someone who shares their enthusiasm. Offer them the gift of some of your previously published work if they express willingness, and a consulting fee if you have the resources. If you find yourself relying on their help at regular intervals, be gracious with a token of appreciation. And of course remember them in your acknowledgments and with a finished copy of the project. Having made friends with several of my sources, the research has become easier; when I start a project in the purview of one of them, I ask for a starting bibliography, which cuts down on steps 1 and 2.

Of course you need a general idea what you want to accomplish when you start researching. That said, I have found it most helpful to let the research inform my outline, particularly in writing historical fiction. I find it most helpful to let the political, cultural and religious climate of a point in history inform my characters’ backstory and upbringing. In fact, I have three rules as I create historical characters in particular: their lives must adhere to or put an interesting (but plausible) twist on their historical record; their lives and actions must be in keeping with their political and cultural setting (even a visionary is only a visionary relative to setting); and ultimately, their pains, joys and actions must ring true to human nature.

My research library for my first book consisted of some fifteen items. My library for Iscariot, more than 100. There’s an inherent risk in so much information and it is this: the temptation to put every tasty morsel of obscure but fascinating information into your prose.

Don’t do it.

Despite my telling myself this advice, my first draft of Iscariot was 800 pages. Part of that is my own habit of over-writing first drafts. The other part of that was an overabundance of interesting stuff. Too much clever innuendo that required first educating the reader.

Readers are not reading fiction to be educated, but entertained (or else they would be reading the same research material as you). Take the time to read and absorb everything pertinent—not for their sake, but yours. Sort your information in a way that you can find what you need when you need it. These days, I organize information by topic in Scrivener. But having absorbed everything I’ve read, listened to, and watched, I try to push it all away when I sit down to write. I let loose, keeping maps or immediate references nearby if necessary, but adding historical details in very small doses later—and mostly to the first part of the novel, where I am buying credibility with the reader.

Save yourself the trouble of hashing through a barrage of information by cutting to the heart of your story from the get-go. Because ultimately, the storyline that will draw and keep your readers is not the product of your diligent research (that will only keep you out of hot water with the critics)… but the emotional connection with a character’s hopes, dreams, failures and fears—the things that bind us all, regardless of time and place.

—————–

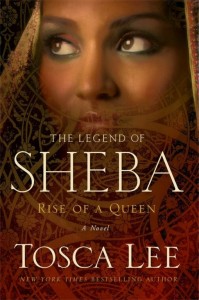

Tosca Lee is the award-winning, New York Times best-selling author of Iscariot; Demon: A Memoir; Havah: The Story of Eve, and the Books of Mortals series with New York Times best-seller Ted Dekker (Forbidden, Mortal and  Sovereign). Her highly anticipated seventh novel, The Legend of Sheba, releases September 9, 2014.

Sovereign). Her highly anticipated seventh novel, The Legend of Sheba, releases September 9, 2014.

Tosca received her B.A. in English and International Relations from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts with studies at Oxford University. She is a lifelong world adventure traveler and makes her home in the Midwest. To learn more about Tosca, visit www.toscalee.com.

For a limited time, download ISMENI, the eShort prequel to SHEBA for free.