by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

“La Barbe Bleue” (Bluebeard) is a French folk tale, first published in 1697. It tells the story of a rich man with an odd, bluish beard who marries women, slits their throats, and hangs their bodies on hooks in the basement of his castle.

“La Barbe Bleue” (Bluebeard) is a French folk tale, first published in 1697. It tells the story of a rich man with an odd, bluish beard who marries women, slits their throats, and hangs their bodies on hooks in the basement of his castle.

Thus, Bluebeard became the sobriquet for a murdering husband. Of which there have been many.

Like James P. Watson of Los Angeles, who was nabbed by the Nick Harris Detective agency in 1920.

Who was this guy?

Well, he was no looker. But somehow he managed to charm women into marriage, first by placing classified ads that said “Would be pleased to correspond with refined young lady or widow. Object, matrimony. This advertisement is in good faith.”

And he got lots of letters in response. He would go through them and weed out the ones he thought were not “quality,” then set up appointments with the others. It would be in a fancy hotel, and the well-dressed Watson would entice them with promises of a home, world travel, the finer things in life.

Those who took the bait headed to the altar, usually within weeks. As soon as the happy couple got into a home, Watson would announce that he had to be away for awhile on business….because he worked for the government trying to nab diamond smugglers. Then he’d go visit some of his other wives, and dispatch a few of them.

It was a game to him.

According to a story by reporter Katie Dowd:

In 1918, he took at least three wives, two in Canada and one in Seattle. Marie Austin of Calgary was the first to die. On a vacation in Coeur d’Alene, he bludgeoned her to death then weighted her body with rocks, sinking her to the bottom of a lake. The Seattle wife was next to go — and fast. For their honeymoon, they took a trip to see a waterfall near Spokane. As she admired the view, her husband came up behind and gave her a firm push.

Sweet guy.

In 1920 he brought a new wife, a widow named Kathryn Wombacher, to settle in Hollywood. Shortly thereafter, he went on one of his “work trips.” Kathryn grew suspicious, and went to the Nick Harris Detective Agency.

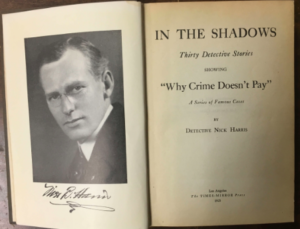

Nick Harris (1882-1943) had been a reporter on the police beat for the L.A. Daily Journal who did such a good job he was offered a sergeant’s desk on the force. This he kept until 1906 when he opened his own detective agency.

He became famous, resulting in some screenwriting gigs and later a radio show about his exploits. For 21 years he did a weekly broadcast aimed at the youth, ending with the phrase that became part of our lexicon: “Crime doesn’t pay.”

He became famous, resulting in some screenwriting gigs and later a radio show about his exploits. For 21 years he did a weekly broadcast aimed at the youth, ending with the phrase that became part of our lexicon: “Crime doesn’t pay.”

So Harris assigned a couple of his men to surveil Watson. When he left on a “work trip” they searched the house and found a locked bag they proceeded to open. Inside they found numerous marriage licenses, wills, jewelry, and letters from women on his list to marry. They turned the evidence over to the police

When Watson returned he was arrested and charged with bigamy.

He then told them there was more going on the met their eyes. He confessed to numerous murders and led the police to one of the bodies.

Why did he so easily offer himself up? Later profilers would opine that he had reached “burn out.” He was tired. And, in true sociopathic style, was proud of demonstrating how he fooled the cops for years.

Why did he so easily offer himself up? Later profilers would opine that he had reached “burn out.” He was tired. And, in true sociopathic style, was proud of demonstrating how he fooled the cops for years.

Watson pled guilty was given life in San Quentin.

Women still wanted to see him.

He wrote love poems and submitted them, without success, to the magazines. One of them was titled “My Ideal Wife.”

He died of pneumonia in 1939.

Nick Harris died of a heart attack in 1943. His agency is still in operation.

As is the first private detective firm, the Pinkertons.

The “private eye” was born in 1850. Private eye is not a colloquialism for private investigator, or PI. Alan Pinkerton, a Scottish immigrant and “cooper” (a worker of wood for barrels, buckets and the like), became a detective for a local police station in Illinois. From there he founded his agency and went national, with a high degree of success. The logo of the Pinkertons was an eye, with the saying, “We never sleep.”

That’s why they are called “private eyes.”

And on a coincidental note, it was 183 years ago yesterday that the first true “detective story” was published: “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” by Edgar Allan Poe. It set up some tropes (see Kris’s post) that are still with us: the eccentric-thinker detective (Poe called this “ratiocination”), the sidekick-narrator (Dr. Watson, anyone?), and crossing swords with the local police. And, of course, the great puzzle mystery solved at the end and explained. [On a side note, I say it’s also an example of the big cheat, because there is no way to figure out how the murders were committed without a great big dose of implausibility supposedly made plausible, and in so ridiculous a fashion that I have a theory Poe meant this story to be something of a joke.]

The private eye became a fixture in American literature when a former Pinkerton detective, Dashiell Hammett, wrote The Maltese Falcon, serialized in the famous pulp magazine Black Mask in the late 1920s. Sam Spade was first played in a movie version in 1931 by Ricardo Cortez, a Jewish actor who changed his name and parlayed his “Valentino looks” into movie stardom (short-lived, as his acting was less than stellar). Bogart, of course, immortalized the role in the 1941 version directed by John Huston.

Wave after wave of private sleuths hit the pulps, but none so successfully as Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe. Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer caught on in the 50s and 60s, followed John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee. Also hugely popular was Shell Scott in a series written by Richard S. Prather.

In the 70s along came Spenser by Robert B. Parker, breathing new life into the private eye genre.

In the 80s, women got into the act via Sara Paretsky’s V. I. Warshawski and Sue Grafton’s Kinsey Millhone.

In the 90s, Walter Mosley gave us the African American L.A. detective Ezekiel “Easy” Porterhouse Rawlins.

We could mention Tony Hillerman’s Joe Leaphorn, though technically he was a detective for the Navajo Tribal Police, and not a private eye. But he must be mentioned because of an early rejection Hillerman got on his first manuscript. An editor wrote, “If you insist on rewriting this, get rid of all that Indian stuff.”

Is there still a place for private eye fiction? Look at the bookshelves. But as Kris noted, “The trick, if it can be simplified as such, is that you have to take our beloved tropes and turn them into your own.”

Not easy but, for me, entirely worth it.

Keep writing.

And never sleep.