John Gilstrap

Last week, you may have noticed (I certainly hope you did) that I was MIA from my blogging duties thanks to an emergency cholecystectomy. That’s what normal people would call the separation of one’s gallbladder from one’s viscera. Mine had decided to die on me, and it turned out it had intentions to take the rest of me with it. Murderous bastard. In the end, good triumphed over evil, with Mr. GB incinerated in a medical waste bag, and its betrayed sponsor going home to his family.

I had suspected for a few weeks that my gallbladder was plotting against me. Even as two sonograms confirmed that no calculi (gallstones) were present, and that there was no telltale thickening of the organ’s walls—the two diagnostic indicators of cholecystitis—my symptoms persisted, including vomiting and the feeling that a woodland animal was trying to eat its way out of my abdomen. I’m no doctor, but I know when stuff’s not right, and that stuff was not right.

But it also was not perpetual (thank God). My worst attack lasted about 12 hours; most would run their course in four or five hours. When they were done, and I’d had a chance to rehydrate, I would feel more or less normal. Not so the past six weeks, however, in which I had multiple attacks. We’re talking Technicolor attacks here, shot in biological 3-D VistaVision, complete with Dolby sound. As tests came back negative, I was actually disappointed. I knew what I had, dammit. Why wouldn’t the doctors stake their reputations and their futures on my intuition?

The Alamo of gallbladder tests is the HIDA scan (hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid). They inject a nuclear tracer into a vein, and then you lie under a camera for an hour. I actually fell asleep. That is, until the results uncovered my gallbladder’s murder plot. From there, it was directly to the ER, and from there to the OR.

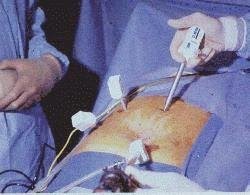

During those few weeks when no one could prove what everyone suspected, I did research on my own. The Internet teems with information on cholecystitis and cholecystectomies. You can actually watch videos of full operations. I learned a lot about laparoscopic procedures and about the function of the gallbladder. Since this was my first medical procedure of any import, and because my personality borders on obsessive-compulsive, my thirst for knowledge was insatiable.

And for all that, I never did find the common-sense answers to the practical questions that concerned me the most. So, with the guarantee of providing way too much information, here, for the benefit of others, are the answers I wish I had found (not that the answers would have changed anything):

1. Yes, they shave you for laparoscopic surgery. Crown of my head notwithstanding, I am a fairly furry fellow, and at the risk of sounding vain, this is the summer season, and, well, you know. I was concerned. For good cause. They mowed everything from the right of mid-left abdomen, from nipple line to pubic line. They do it after you’re sedated. Now that it’s done, the cosmetics worry me less than the prospect of a lot of itching over the next few weeks. (Months? I have no idea how long it takes to grow back.)

3a. Note to nurses everywhere: When you’re talking about shoving a 15-inch tube into a man’s winkie, you have to choose your words carefully. I heard “long term” and panicked. Turns out they were thinking along the lines of 18 hours. Sorry, ma’am, but unless you’re a fruit fly, 18 hours is “short term.”

5. A two-day hospital stay for laparoscopic surgery makes you fat—but only for a while. Between the gas they pumped into my belly for the surgery and the fluids they flowed into me to keep me alive, I came home with three inches more girth than when I first checked in. Good news: physical activity (i.e. walking) triggers the mechanisms to relieve the discomfort. Bad news: you don’t want to be in genteel company when those mechanisms kick in. I literally peed away six pounds in my first 24 hours at home. As for the residual gas, well, you get rid of that exactly how you would imagine.

I apologize that none of this is topical to the subject of this blog, but since you’ve read this far, allow me one last indulgence. I write books about people who save the lives of perfect strangers, but this is the first time that I’ve ever played the role of the stranger. People I’d never met literally worked overtime to return me to my family with a shining prognosis. I make light here, but understand that the humor is a cover. How do I return that kind of favor? The phrase, “thank you,” seems sort of hollow under the circumstances, but it’s all I’ve got.