Vigilante heroes – including Dylan Hunter, the hero of my vigilante thriller series – break lots of laws and conventions. I confess that I occasionally do the same about the laws and conventions of fiction-writing.

For instance, one cardinal rule, taught by many fiction instructors, is:

Avoid expressing your personal views about politics, religion, and other controversial issues in your fiction.

Your job as a novelist, they say, is solely to entertain—not to “preach.” If you get up on your soap box, you’ll only alienate many potential fans. To attract a broad readership, you should suppress the desire to push divisive “agendas.”

Or, as movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn famously admonished a screenwriter: “If you want to send a message, call Western Union.”

But is it true that you shouldn’t express controversial views in popular fiction?

Well, it is true that readers of popular fiction don’t want to be lectured to or harangued. Some authors, believing they have important ideas to convey, beat readers over the head with their views. In static scenes on porches, in drawing rooms, and around dinner tables, characters don’t converse; they deliver speeches and soliloquys. Too often, these wooden, one-dimensional “characters” are little more than premises with feet.

I had to confront this issue head-on when I decided to move from nonfiction into fiction. You see, I have strongly held views and have never hidden them. My writing career began with “advocacy” journalism: essays, reviews, and other opinion pieces. So, when I decided to write thrillers a few years ago, it felt natural to incorporate my views into my stories.

First, I rejected the belief that there’s an inherent contradiction between entertaining fiction and thought-provoking fiction. Shakespeare, Ibsen, Hugo, Dickens, Tolstoy, Orwell, Dostoyevsky, Rostand—all wrote works that entertained millions while taking sides on the controversies of their times. Taken literally, the “no politics” rule would have deprived the world of Les Misérables, 1984, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin—serious novels of ideas that still won vast popular audiences.

Moreover, if you watch marketing expert Simon Sinek’s influential talk, “Start With Why,” you’ll see that building compelling stories around your passionately held beliefs can become a great marketing strategy. They will attract those who share your views, making them loyal fans, even evangelists for your work. Distinctive views also help to “brand” you, making you and your work stand out from the crowd and become more visible.

But how can authors with “something to say” avoid the pitfalls of heavy-handed preachiness? And how do I incorporate controversial ideas into popular thrillers, without turning off readers looking mainly for a good rollercoaster ride?

I think many opinionated writers fail to entertain because they engage in extraneous pontificating, rather than make their ideas integral to the stories themselves. The trick is to weave a provocative theme or premise into the very fabric of your story, making it the thread that connects your characters to each other and to the events of the plot.

In his classic how-to, The Art of Dramatic Writing, Lajos Egri devotes the first chapter to structuring a story upon a “premise.” Egri shows how to develop a controversial theme, first by creating major characters that hold uncompromising, opposing positions. Their clash of values drives the plot’s central conflict, which is resolved at the climax. The climax “proves” the story premise. Minor characters play complementary roles, representing “variations on the theme.” (Of course, your challenge as a literary craftsman is to make your characters seem three-dimensional and fully real—and not mere mouthpieces for arguments.)

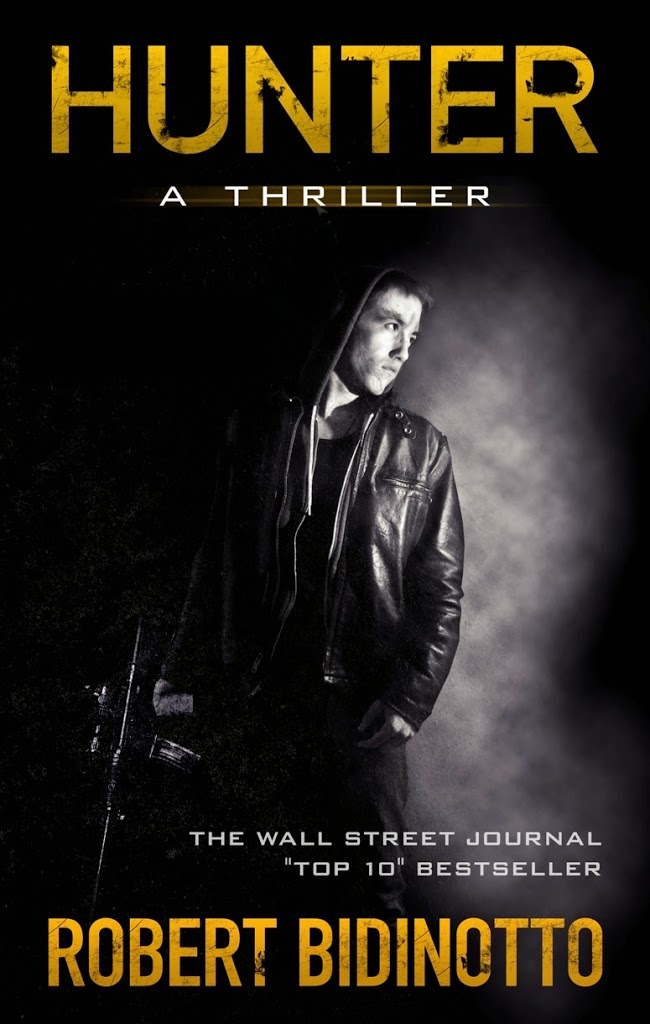

I used Egri’s approach with my first thriller, HUNTER, which draws upon my past investigative reporting about the criminal justice system. It dramatizes the outrageous leniency I discovered, in which vicious criminals are routinely recycled back onto the streets to prey on new victims. The major antagonists are my hero, mysterious investigative journalist Dylan Hunter, and a wealthy philanthropist funding “alternatives to incarceration.” The complication is that Dylan doesn’t know that his sworn enemy also happens to be the father of the woman he loves.

This orchestration of characters allows the thriller’s theme—the injustices caused by excessive leniency—to be not only articulated and argued, but to be dramatized in action, with all the scary violence, intense suspense, and sizzling romance that thriller fans expect.

For the sequel, BAD DEEDS, I set the story in even more controversial territory: the clash between environmentalists and the “fracking” industry. Here, my views are not what most readers would anticipate. But once again, I present villains who uphold ideas and values opposite those of my hero. Once again, the plot brims with action, suspense, colorful characters, and white-knuckle thrills. And once again, the climax “proves” the theme.

At first I feared that my maverick opinions would turn readers off. Instead, HUNTER became a Kindle and Wall Street Journal bestseller. And the even-more-controversial BAD DEEDS is maintaining an Amazon customer rating of 4.9 out of a possible 5.0 points.

So, if you write mysteries and thrillers, relax! You don’t have to avoid touching hot-button controversies. In fact, doing so can become a badge of distinction, helping your work to stand out in the overcrowded marketplace. I describe my novels as “thrillers for thinkers.”

And in an era of recycled plots and worn genre retreads, that’s not a bad brand.

Robert Bidinotto is author of the Kindle and Wall Street Journal bestselling thriller, HUNTER, and the thrilling sequel, BAD DEEDS. Robert earned a national reputation as an authority on criminal justice while writing investigative crime articles as a former Staff Writer for Reader’s Digest. His famous 1988 article, “Getting Away with Murder,” stirred a national controversy about crime and prison furlough programs and was named a 1989 finalist for a National Magazine Award. Robert is author of the acclaimed nonfiction book Criminal Justice? The Legal System vs. Individual Responsibility. He also wrote Freed to Kill—a compendium of horror stories exposing the failings of the justice system. Robert drew upon this background and his personal experiences with crime victims to write HUNTER.