“It is the glory of God to conceal things, but the glory of kings is to search things out.” – Proverbs 25:2

“Attempt the end, and never stand to doubt. Nothing’s so hard but search will find it out.” — Robert Herrick

* * *

Since all human beings (not just kings) love to figure things out, I thought the Kill Zone Blog might be a good place to examine the history of the sleuthing mystery genre. A look back in time may even give us clues to facilitate our own successes. So grab your flashlights and let’s enter the dark and web-encrusted chambers of crime. The game’s afoot!

* * *

The format of a mystery novel is straightforward. The story usually begins with a crime being committed. It can be a murder, a suspicious death, a disappearance, even a theft. The rest of the story involves the search for the truth and ends with answers to the questions: who committed the crime, how, and why.

Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) is generally considered to be the first modern murder mystery, and its detective, Auguste C. Dupin, the first fictional detective. There was no monkey business in Dupin’s analysis of the horrific crime and identification of the murderer.

Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) is generally considered to be the first modern murder mystery, and its detective, Auguste C. Dupin, the first fictional detective. There was no monkey business in Dupin’s analysis of the horrific crime and identification of the murderer.

Wilkie Collins was a contemporary of Charles Dickens and is credited with the first novel-length mystery, The Woman in White (1859). The book doesn’t just stop at murder – it also touches on insanity, social stratification, false identity, and a few other themes. Collins considered the book his best work and instructed that the phrase “Author of The Woman in White” be inscribed on his tombstone. He also lays claim to the first detective novel, The Moonstone (1868).

Wilkie Collins was a contemporary of Charles Dickens and is credited with the first novel-length mystery, The Woman in White (1859). The book doesn’t just stop at murder – it also touches on insanity, social stratification, false identity, and a few other themes. Collins considered the book his best work and instructed that the phrase “Author of The Woman in White” be inscribed on his tombstone. He also lays claim to the first detective novel, The Moonstone (1868).

Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, the first story featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, in 1887. In total, Doyle wrote 56 short stories and four novels featuring the famous detective. When he killed off Sherlock Holmes in The Final Problem (1893), the public outcry was so severe, Doyle had to bring him back in later works.

Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, the first story featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, in 1887. In total, Doyle wrote 56 short stories and four novels featuring the famous detective. When he killed off Sherlock Holmes in The Final Problem (1893), the public outcry was so severe, Doyle had to bring him back in later works.

Maurice Leblanc began a mystery series in 1905 featuring the gentleman thief Arsene Lupin, a character who’s been described as a French version of Sherlock Holmes. In all, Leblanc wrote 17 novels and 39 novellas with Lupin as hero. Check out Joe Hartlaub’s excellent blog post about the books and recent TV series based on Leblanc’s hero.

Maurice Leblanc began a mystery series in 1905 featuring the gentleman thief Arsene Lupin, a character who’s been described as a French version of Sherlock Holmes. In all, Leblanc wrote 17 novels and 39 novellas with Lupin as hero. Check out Joe Hartlaub’s excellent blog post about the books and recent TV series based on Leblanc’s hero.

G.K. Chesterton is credited with creating the cozy mystery genre with a series of 53 short stories begun in 1910 featuring the Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective, Father Brown, who uses his intuitive understanding of human nature to solve crimes. The character was so popular, it inspired the Father Brown TV series that began in 2013.

G.K. Chesterton is credited with creating the cozy mystery genre with a series of 53 short stories begun in 1910 featuring the Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective, Father Brown, who uses his intuitive understanding of human nature to solve crimes. The character was so popular, it inspired the Father Brown TV series that began in 2013.

The Thirty-nine Steps (1915) by Scottish author John Buchan was the first of five novels featuring Richard Hannay. a man on the run who had been unjustly accused of murder. There are a couple of movie versions of The Thirty-nine Steps, but my favorite is the 1935 Hitchcock film starring Robert Donat.

The Thirty-nine Steps (1915) by Scottish author John Buchan was the first of five novels featuring Richard Hannay. a man on the run who had been unjustly accused of murder. There are a couple of movie versions of The Thirty-nine Steps, but my favorite is the 1935 Hitchcock film starring Robert Donat.

Cozy mysteries became very popular in the 1920’s and 30’s with several great British authors. Agatha Christie’s first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), featured Hercule Poirot, a sleuth who used his “little gray cells” to solve mysteries. Poirot showed up in 33 novels and over 50 short stories. (I will have much more to say about Dame Agatha in a future post.)

Cozy mysteries became very popular in the 1920’s and 30’s with several great British authors. Agatha Christie’s first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), featured Hercule Poirot, a sleuth who used his “little gray cells” to solve mysteries. Poirot showed up in 33 novels and over 50 short stories. (I will have much more to say about Dame Agatha in a future post.)

Dorothy Sayers introduced her own hero, the elegant but troubled Lord Peter Wimsey, in her 1923 novel Whose Body. Sayers wrote 11 novels in the Lord Peter Wimsey series.

Younger readers joined the mystery caravan with the Hardy Boys series which began with The Tower Treasure in 1927. Several authors contributed under the collective pseudonym Franklin W. Dixon.

The Nancy Drew series entered the parade in 1930 with The Secret of the Old Clock. Again, several authors contributed under the collective pseudonym Carolyn Keene. Many of us credit the Nancy Drew books with our own interest in creating mystery stories.

Hardboiled detective fiction became popular in the 1920’s and extended through the 20th century. Dashiel Hammett became famous for his character Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1929). He also created the sophisticated couple Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man (1933). Strangely, Hammett wrote his final novel more than 25 years before his death. Why he stopped writing fiction is something of a mystery in itself.

Hardboiled detective fiction became popular in the 1920’s and extended through the 20th century. Dashiel Hammett became famous for his character Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1929). He also created the sophisticated couple Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man (1933). Strangely, Hammett wrote his final novel more than 25 years before his death. Why he stopped writing fiction is something of a mystery in itself.

Raymond Chandler was forty-four years old when he began his journey as an author. His first novel, The Big Sleep (1939), introduced the world to private detective Philip Marlowe. In addition to his short stories, Chandler wrote seven novels, all with Marlowe as the hero. His prose is widely admired and his use of similes is famous. Here’s an example from The Big Sleep: “The General spoke again, slowly, using his strength as carefully as an out-of-work showgirl uses her last good pair of stockings.”

Raymond Chandler was forty-four years old when he began his journey as an author. His first novel, The Big Sleep (1939), introduced the world to private detective Philip Marlowe. In addition to his short stories, Chandler wrote seven novels, all with Marlowe as the hero. His prose is widely admired and his use of similes is famous. Here’s an example from The Big Sleep: “The General spoke again, slowly, using his strength as carefully as an out-of-work showgirl uses her last good pair of stockings.”

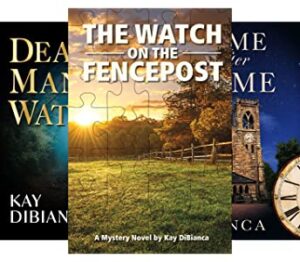

So that completes this survey of the history of mystery. I selected these twelve examples from articles about the subject on various websites including biblio.com and wikipedia.com. Did you notice anything interesting about this list? Almost all of the wildly successful mysteries are series. Food for thought.

* * *

Back to our original question: Why do people love mysteries so much? Maybe it’s because a mystery novel is an example of mankind’s search for truth pared down to its most elementary format and delivered in a 6X9 inch package. The reader knows he/she will be satisfied at the end of the book with the answers of who, how, and why. And justice will be served. That’s a lot to accomplish in just a few hours of reading!

* * *

So TKZers: What is your favorite mystery novel? And who is your favorite mystery novelist? What books or authors would you add to my list?

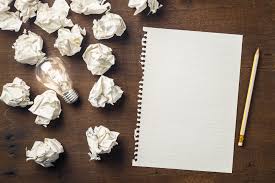

When I begin a new book, I spend some time searching for ideas. Is there some message I want to convey? Or a character who’s anxious to make his/her debut? Is there a particular mystery I want to challenge readers with or a basic theme I’m interested in? I spend time reading good novels and craft-of-writing books. I go for a run and play what-if games. I try not to force the issue, but let my brain relax, hoping for inspiration.

When I begin a new book, I spend some time searching for ideas. Is there some message I want to convey? Or a character who’s anxious to make his/her debut? Is there a particular mystery I want to challenge readers with or a basic theme I’m interested in? I spend time reading good novels and craft-of-writing books. I go for a run and play what-if games. I try not to force the issue, but let my brain relax, hoping for inspiration.