I had three secretaries in the twenty-five years I worked in school district administration. My starter secretary was a Texas wife, mother, and grandmother, who spoke with the slow drawl we all recognize here in the Lone Star state.

My second was from New Jersey. She had little accent until someone angered her, or when talking with her family, and especially her mother. That’s when Jersey came out thick and nasal, dropping her “r”s. You know it as “buttah” for butter, and the “a” sound changed in words like “towk” for “talk” or “dowg” for “dog.”

I tried to write “or” as “oa,” but that didn’t work in the above sentence. It does now, though.

Here we pronounce dawg.

She also took great delight in correcting my pronunciation of “pen.” Where I come from, we say “pin” and for the word “aunt,” “aint.” We also put those abandoned Jersy “r”s in words such as “worsh” for “wash,” and “winder” for “window,” and finally, “piller” for “pillow.”

“Open the winder and hang that piller case out to dry. Someone left a wet warsh rag on it all night.”

Thinking about her pronunciations this morning (and my own) brought up a trail of thoughts about how hard it is read someone’s work when they hammer us with local dialogue for an entire novel or short story. I recently read a story so filled with a character’s regional dialogue that reading became a 6,000-word burden.

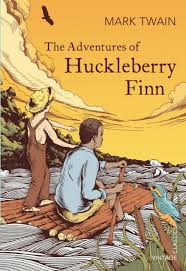

Note to authors: You’re not Mark Twain writing Huckleberry Finn. I love that book, but the dialogue simply wears me out. Use it early in the story to give us that local flavor, or to identify a character, then use it sparingly throughout the book. I don’t need to be hit over the head with it until my skull is misshapen.

Here’s an example of Jim talking to Huck. “Pooty soon I’ll be a-shout’n’ for joy, en I’ll say, it’s all on accounts o’ Huck; I’s a free man, en I couldn’t ever ben free ef it hadn’ ben for Huck; Huck done it. Jim won’t ever forgit you, Huck; you’s de bes’ fren’ Jim’s ever had; en you’s de ONLY fren’ ole Jim’s got now.”

That’s all I need. Now, give me something easier to read.

But back to “pehns,” and writing instruments.

Authors of a certain age began with big fat pencils designed for little elementary school hands.

We progressed to clear, cheap Bic pens which became the norm, but for a period of time, refillable cartridge pens were all the rage in my elementary. I had one of those, but most of the ink went directly from the nib and into highly absorbent Kleenex tissues, which bloomed nice and blue while Miss Russell droned on and on about diagraming sentences.

Because of those psychadelic blooms, and a distinct lack of interest, I still can’t diagram a sentence.

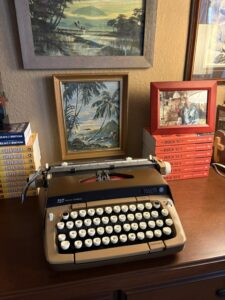

My writing output began with a Smith Corona portable typewriter, though the volume of work between 1970 and 1988 was dismal at best. I made beer money with it, though, typing term papers and reports all during college.

It was a 286 computer that finally set me free, and I haven’t looked back since. They keyboard is my friend, and I’m danged fast on this thing. I used to write newspaper columns on yellow legal pads (when I should have been listening in meetings…do you sense a pattern here?), and typed them into a floppy disk to print out on a tractor drive.

Those were the days.

I can’t write longhand anymore. My handwriting is somewhat akin to that of a doctor with alcoholic shakes, and I can’t make out what I scribbled.

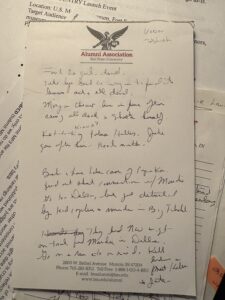

So all I do is make hundreds of notes on small pieces of paper, which I forget or lose until months later. Sometimes those notes make no sense, and I have to wonder what idea had been rattling around at that time.

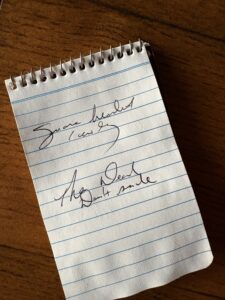

Others are great, and I’ll find somewhere to plug them in on this WIP. If you can’t read the top scribble, it says, “square-headed cowboy,” and the second is a possible book title, “The Dead Don’t Smile.”

I know authors who write longhand. Bestselling author Marc Cameron, of Arliss Cutter and Tom Clancy fame, and I were at an in-conversation signing a couple of weeks ago and he discussed his method of getting the first draft down with a box of Blackwing 602 pencils and a stack of legal pads. When he’s finished, he types it up and gives the pencil stubs away to fans.

All I would have is a stack of pads full of hieroglyphic scrawls that I couldn’t read no matter how hard I squinted at them with one eye.

But then I got to thinking about signing pens. That’s kind of a big deal to some folks, and here’s a question for the hive mind (and truly the point of today’s post).

What pen is best for signing copies of my work?

Some authors prefer old-school fountain pens, but I can’t keep them flowing. I’ll leave them on the desk for a couple of weeks and then have to soak the ink away. That’s irritating, though I love the looks of those instruments both in hand, and the way they write.

I have half a dozen pen sets that were given to me over the years. One set came from my mother when I graduated college. Now an antique, the pen and mechanical pencil is hand-turned walnut, and I used it for so long the oil from my fingers has stained the wood so deep it glows with a soft polish.

I don’t use it though, because I’d leave it laying somewhere. Note: Now I’m of the age I can’t find things. I went to get them for a photo to use here, and can’t remember where I put them so they wouldn’t get lost.

Sigh.

To make signatures special in my mind, I use pens (pehns) from the 21 Club in New York City. It was the haunt of my original writing mentor, Robert Ruark, (who passed in 1964). The las time I was there, they gave me half a dozen of those black pins (Texas for pens), with gold lettering, and sometimes fans notice when I’m signing and ask about them. That’s fun.

You can’t get them today, though. Covid killed the pre-prohibition club that had been open for over 90 years.

I’ve used a variety of rolling balls, and many almost skidded off the page. I loved them all, but as I said, I lost them and can’t remember which ones were the best.

I do not like signing with Sharpies. Period.

So, to all the authors out there, which do you use as your “signing pehn,” and where do I get one to try out?

It won’t be this one, though. It’s a scary weapon, I think.

I’m left-handed, so I need a pen that won’t smear. So far the best one I found is a Bic velocity. But my favorite pen is one my friend Steve Hooley gave me that he made from wood back in the 1700s.

Always sign books at home with that one – like you I’m afraid I’ll lose it.

Rev, the best-feeling, best-writing pens are made by TKZ emeritus Steve Hooley. He hand-turns old lumber he’s salvaged from historic buildings or wood harvested from his family’s forest. The pens are gorgeous, high-quality, and comfortable in the hand.

He also custom designs pens and has created unique models for Kay DiBianca and me to go with our books. https://stevehooleywriter.com/legacy-pens/

I’ll echo the above praises for Steve Hooley’s pens. I have two: a roller and a cartridge. I don’t like to use a fountain-type pen for signings because the ink can soak into the paper. They were a requirement in my 9th grade science class, though. Ballpoints (no rollerballs or gels then) would leave ‘undigested blobs of ink’ on the page, per Mr. Webster.

I use a Sarasa Zebra clip pen 0.7mm to sign my books. The ink dries immediately, no smearing, and is easily read. I always have a small paper pad to check spelling for dedications, too.

I have given these pens to all my left handers. They never get ink stains on their hands with this pen.

I have a pen just like your scary weapon, and that’s exactly what it is. I got it at the Spy Museum in DC.

When my first book was published, my mother gave me a set with my pen name engraved on them. I was supposed to use them for signings but was too afraid they’d go missing, so instead used a Pilot BP-S Fine stick pen. I have used these for 40 years. They never skip or leave blobs, and they work all the way to the last drop of ink in the barrel. I throw the caps away and use cushy slip-on finger grips. Not pretty, but effective and reliable.

I learned to write using the Palmer method, which results in a curly style. I’ve always had a fascination with pens, and love to browse the catalogue for Fahrney’s pens in DC. When I got a contract for my first novel, I treated myself to a Mont Blanc roller ball with a black barrel and gold bans, but I wouldn’t take it on the road because I didn’t want to lose it. I usually wind up signing with whatever pen I swipe from the hotel room. I just saw Steve Hooley’s pens. They put Fahrney’s to shame.