by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

We’ve had some robust discussions over the years on this matter of “rules” for writers. That word always seems to raise hackles (hackles, n., the erectile hairs along the back of a dog or other animal that rise when it is angry or alarmed).

There are two standard rejoinders when someone mentions “rules” for writing fiction.

First, somebody will inevitably quote Somerset Maugham’s dictum: “There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.” (There, I did it for you.)

The second reaction is more direct: “There are no rules!” (Always with the exclamation point.)

Now, while I don’t recoil at the word rules, my preferred nomenclature is fundamentals. What makes something a fundamental? It works. Fundamentals keep the writer—especially the novice—from obvious errors that frustrate the basic relationship between writer and reader.

“Your mother was a hamster…”

But slip in the word rules and a chorus will rise, with variations on the theme: “Shackle us no shackles! A pox on your rules! And your mother was a hamster and your father smelt of elderberries!”

I believe the root of this objection is really a tacit recognition that rules have exceptions. But you’ve got to know a rule before you understand the alternatives. You’ve got to learn the scales before you start playing jazz. You’ve got to master the two-handed chest pass before you start with the no-look, behind-the-back dish. (“Pistol” Pete Maravich and Earvin “Magic” Johnson practiced the fundamentals for countless hours before they became magicians on the court.)

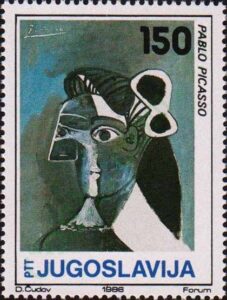

As Alice K. Turner, for many years the fiction editor at Playboy, put it: “If you’re good enough, like Picasso, you can put noses and breasts wherever you like. But first you have to know where they belong.”

The above was throat clearing. Now on to today’s post!

CATO and Its Exceptions

Let’s discuss the character alone, thinking, opening (CATO).

You want readers to connect to your story from the jump, right? I mean, what’s the alternative?

Long experience tells me that the fastest way readers are pulled into a story is when they see a character in motion responding to a disturbance. This is a fundamental for a simple reason: it works every time.

The CATO, on the other hand, is too often slow and uninvolving. The writer thinks that jumping immediately into the inner sanctum of a character’s mind will create for the reader the same emotional bond the writer has with the character. But that’s because the writer has lived and breathed with that character, and knows how the character acts and reacts. Readers don’t know those things yet. They need to see action before they care about thoughts.

That’s why writers are well advised, as a general rule guideline, to avoid the CATO.

Unless…they know how to bring something more to it.

In a TKZ Words of Wisdom we revisited a post by our own Kris (P. J. Parrish) on the subject of openings. This quote struck me:

But I’m tired of hooks. I’m thinking that the importance of a great opening goes beyond its ability to keep the reader just turning the pages. A great opening is a book’s soul in miniature. Within those first few paragraphs — sometimes buried, sometimes artfully disguised, sometimes signposted — are all the seeds of theme, style and most powerfully, the very voice of the writer herself.

Note two things here. First, Kris knows what a hook is. She knows the “rule.” Second, she gives a solid reason for breaking it and mentions, in my view, the most important element—voice.

Let’s look at an example from a surprising source, one Mickey Spillane, in his classic, One Lonely Night.

Mike Hammer novels usually start off like a blast from a .45, in the middle of hot action. But in his fourth Hammer, Spillane breaks his rule because a) he knows exactly why he’s doing it; and b) he could flat-out write. Here’s the opening graph:

Nobody ever walked across the bridge, not on a night like this. The rain was misty enough to be almost fog-like, a cold gray curtain that separated me from the pale ovals of white that were faces locked behind the steamed-up windows of the cars that hissed by. Even the brilliance that was Manhattan by night was reduced to a few sleepy, yellow lights off in the distance.

The mood, the setting, the word choices, the weather (another broken “rule”). The style is immediate and compelling. For the next four pages we have Mike Hammer walking across the George Washington Bridge, thinking.

But what a think it is! It is packed with emotional turmoil that grips and thrashes nothing less than his immortal soul.

He’s thinking about the complete dressing down he got from a judge earlier that day. Hammer was brought in because he’d killed a man, but in self-defense. That didn’t matter to the judge who knew Hammer’s record as a killer of bad guys. Before he lets Hammer out, the judge makes it clear to Hammer and the courtroom that the PI “had no earthly reason for existing in a decent, normal society.”

He had looked at me with a loathing louder than words, lashing me with his eyes in front of a courtroom filled with people, every empty second another stroke of a steel-tipped whip. His voice, when it did come, was edged with a gentle bitterness that was given only to the righteous.

But it didn’t stay righteous long. It changed into disgusted hatred because I was a licensed investigator.

Now, Spillane being Spillane, he knows he can’t stay inside Hammer for a whole chapter. Of course he gets to the action—and man, what action it is!

A girl is running across the bridge, abject fear in her eyes. Someone is after her. Hammer tells her, “Just take it easy a minute, nobody’s going to hurt you.”

A man emerges from the shadows. He’s got his hands in his coat pockets, but clearly has a gun, his “lips twisted into a smile of mingled satisfaction and conceit.” The guy doesn’t realize Hammer carries a .45.

I blew the expression clean off his face.

The action doesn’t end there. The girl screams “as if I were a monster that had come up out of the pit!”

She jumps on the rail and Hammer tries to grab her, but “she tumbled headlong into the white void below the bridge.”

And Hammer is left there with the dead guy’s body, thinking:

I did it again. I killed somebody else! Now I could stand in the courtroom in front of the man with the white hair and the voice of the Avenging Angel and let him drag my soul out where everybody could see it and slap it with another coat of black paint.

He proceeds to search the dead man.

If his ghost could laugh I’d make it real funny for him. It would be so funny that his ghost would be the laughingstock of hell and when mine got there it’d have something to laugh at too.

Finished with the body:

I grabbed and arm and a leg and heaved him over the rail, and when I heard the faint splash many seconds later my mouth split into a grin.

Wow, talk about action. Talk about Spillane’s famous adage The first chapter sells that book. The last chapter sells the next book.

Spillane ends the chapter by connecting back up with the beginning:

I reached the streets of the city and turned back for another look at the steel forest that climbed into the sky. No, nobody ever walked across the bridge on a night like this.

Hardly nobody.

That’s style. That’s voice. That’s how you break a rule. And you can do the same, if you nurture your own voice…and if you first know where to put noses and breasts.

Discuss!

Note: If you want to know how to find and nurture your unique voice, this will help.

Writing is closer to alchemy than anything else. Alchemy was not primitive chemistry, nor was it about making gold from lead, or creating magical substances–universal solvents, philosopher’s stone, etc.

No, alchemy was about human transformation and transcendence. A writer’s alchemy consists of all the elements he/she crams into the writing, elements that alter readers, cast spells upon them, make them invest in characters, elements that include things like connections between the reader and the MC, a hypnotic voice, visuals that draw readers into scenes, reversals that shock them, puzzles that mystify them, hints that create tension and make them worry what will happen to the MC, and so on. It may seem like magic to readers, but it’s craft. The operative rules are not so much about the craft details, as about the underlying alchemy that puts readers under the writer’s spell and keeps them there.

I like your reference to alchemy, J. Indeed, I wrote post about it.

Very cool. Link, Mr. Bell?

The writing process, whether for novels or film scripts, has been characterized by many metaphors. Examples include building a bridge, painting a picture, hanging a clothesline, mapping an unexplored territory, opening a closet, making a sculpture, building a house, laying pipe, mining, surfing, riding a horse, and hunting. And I’ve compared it to making your way through a maze, elsewhere.

Brilliant. All my favorite themes!

I did something instinctively, almost a quarter of a century ago, and I still like it: I tell my story through the roughly alternating points of view of three main characters – and each one gets a fully developed scene in the first chapter, bam bam bam!

They are very different – but you get enough (deep close third person pov) of each to know who you are going to be traveling with for the rest of the book, where the characters are, and what is going on – and the beginnings of the significant conflict they will have.

What I found interesting was that a couple of the reviewers mentioned they had noticed they didn’t get a whole setup chapter for each main character. But they didn’t complain; just noticed.

And yet I have no idea where I got it, except that I didn’t like having a whole chapter from the FIRST person pov of each character – as Margaret Atwood did in Life After Man. First person to me means identification for the length of the book – and that wasn’t what I wanted to do.

Voice includes all the things you WON’T do, too.

Interesting approach, Alicia. Sounds a bit like The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thonton Wilder, or The Damned by John D. MacDonald.

In “An Instance of the Fingerpost,” Iain Pears does the same thing, using four major sections.

I needed to give the VILLAIN a proper voice, or the whole thing wouldn’t work. Some people even like her better. And she’s SO right about many things.

But taking a huge risk guarantees nothing – and the consequences must be borne anyway, and sometimes by people who did not agree to the possibility.

Right!

Couldn’t begin to agree more with the title of your post. I also agree with the basic tenet that there are absolutely NO rules about writing, or the wimpier, no-stance notion that “There are no rules; they’re only guidelines.”

Still, no rules re grammar, punctuation, syntax, etc. matter. You know, unless you actually WANT the greater number of readers to understand what you’ve written and take from it what you want them to take from it.

In that case, you must learn the rules, not so you won’t break them, but so you can break them intelligently and intentionally to create a certain effect in the reader.

There really is no way around the advice of Steven Pressfield and countless others: Do the work. Learn with the conscious, critical mind and (if you’re writing fiction) apply with the creative subconscious. The combination is unbeatable.

“…you must learn the rules…so you can break them intelligently and intentionally to create a certain effect in the reader.”

Yep.

The creative subconscious, by whatever name, is ideal for writing. It is fast, has excellent memory access, can juxtapose potential elements rapidly, and is able to brainstorm effectively because it has no conscience.

Great post, Jim.

I’m still learning the rules, so not in any position to start trying to break them.

I will say that Voice is a huge part of what I look for in a writer when I am looking for a book to read. I enjoy the long internal monologues and descriptions that hint at the writer’s background and experiences.

I hope your day is filled with the voices of your grandchildren.

So agree, Steve. Voice is truly the “secret power,” from Ishmael to Philip Marlowe; Huck Finn to Scout Finch.

Love this example of using voice to seemingly defy “rules”, Jim. It’s a very powerful opening because of that voice, and yet, as you note, Spillane does give us action, and more action, once he’s established the context for Hammer at the opening of this novel, using that voice to pull us into the story. Wow. The action is all the more powerful because we’ve learned what Hammer had just been dealt by a judge earlier.

Voice, the “secret sauce” of fiction.

“Secret sauce” is the key to both fiction and great burgers, e.g., In-N-Out. 😎

Perfect timing for this post as I’ve delved into my periodic high brow reading phase I enter to cleanse the palate. This time, I’m delving into the work of the late Cormac McCarthy.

On the surface, boy oh boy did he break a lot of rules. However, the writer reading his work needs to understand he did indeed pay for this in that he had (and has) a relatively small readership, and which is mostly comprised of aspiring writers saying, “why can’t I break the rules too!?”

That said, he followed a fundamental: make your book enjoyable to read, whatever it takes. And for a certain group of readers, myself included, he succeeded.

That’s a good topic for discussion sometime, Philip. What is the “craft” of rule breaking, and is the cost (fewer sales) worth the price?

Maybe 3 or 4 discussions! Or ten.

Wow, Jim. The excerpts from One Lonely Night in your post provide a whole course in voice and hook.

I am dedicated to writing mysteries. I start with my “rules” that the mystery itself must be clever, and the characters must be memorable. Then I (try to) fold in all the things I’ve learned from craft books (I think I have all of yours, Jim) and other great writing tips found here at TKZ and on other blogs in order to tell my story. But in my heart of hearts, I’m an experimentalist, so I may bend the rules here and there just to see what happens.

The idea of “voice” is still elusive to me, though, but I’ve been pleasantly surprised by reviews from readers who say they like my style and the way I write. Maybe it’s time for me to re-read your Voice: The Secret Power of Great Writing.

Far be it from me to discourage you from one of my books, Kay. Ha!

I like your idea of “bending” a rule here and there to “see what happens.” That’s what beta readers are for.

Oh good Lord. I think I see what’s wrong with my opening. I like it, but I know and love this character. Anyone else would be bored. I think I know how to fix it. Thank you.

Love it when that happens, Cynthia. Glad to be of service!

Haha! There’s the Rule of Rules: Don’t be boring!

Jim, Voice is my favorite craft book of yours and I recommend it to other writers all the time.

Now I have to read <One Lonely NIght. Thanks for adding to my already-towering TBR pile.

Thanks for that, Debbie.

Yes, that ol’ TBR pile grows like kudzu, doesn’t it? A week ago I cleared off a table by my favorite reading chair. Now it’s got five books on it. Ack!

As Matthew McConaughey—or someone—might say: Right on, Right on!

Awright awright awright.

What a perfect example of voice and breaking the musing and weather-opening rules, Jim. Your spiffy new profile pic is pretty jazzy, too. 😉

I enjoy “pushing the boundaries” when it comes to some rules. What I never do is break a structural rule, like milestone/signpost placement, or it’d ruin the reading experience.

That’s exactly what should be primary, Sue. Always. We owe the reader the best experience we can give them.

One thing newer writers don’t understand is that established authors have both a reputation and fans who will be patient for that slow opening and trusting that the author knows what they are doing when expectations/rules are broken. Newer writers have none of this, and that the slow first chapter and other failed “rules” may be the last thing a reader will see before they toss the book and find another one.

In most classes and seminars I’ve taught over the years, I almost always have one student who believes rules don’t exist for them and their crap doesn’t stink. I say something even though I know they won’t listen, and I’ll never see anything by them in print. I just pity the next teacher who has to deal with the arrogant snot.

The difference now is that those “students” can publish whatever they like, over and over again, with a click. Their output grows, but not their bank account.

I have heard it said that there is only one rule and that is “Don’t be boring.” All else is vain.

That being said, the apprentice scriveners like me can do well to study the maxims of the established writers in their chosen genre when learning the trade, like Elmore Leonard’s ten rules.

It’s no different than learning how to be a bricklayer or an electrician or plumber. I reckon when Sir Winston Churchill was cast into the wilderness before the war and he built a brick wall at Chartwell, that he knew something about the masonry trade.

https://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/16/arts/writers-writing-easy-adverbs-exclamation-points-especially-hooptedoodle.html?searchResultPosition=1

Paywall.

I’ve been to Chartwell.

Gee, first, thanks for the kind shout-out. I still believe what I said about cheap and easy hooks. But to your point about Spillane…

Great example of an excellent slow build opening. Would the action have been so compelling without Spillane first giving us a glimpse into his character’s state of mind, his mood, his recollection of the court scene? I think not. As you said, this is a splendid example of the writer, so in control if his craft, that he can risk long moments of dark thoughts…BECAUSE they provide an emotional context for the action that comes soon after.

But he is smart to not dwell too long in the past, too long in thoughts about the judge. He gets to the action. And the scene, as you point out, has this lovely circular structure — agonized thought, action, agonized reaction-thought with that great echo-line about nobody walking the bridge on the night like that.

And man, don’t you just LOVE that line: “I blew the expression clean off his face.”

I do love it, Kris. And thanks to you for giving me the idea for this post!

As a self-taught writer, other than the grammar I learned in school, I was oblivious to most of the ‘rules’. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing, but it does keep the ‘fun’ quotient up.

I suspect as a reader you soaked up “rules” by osmosis!

I have rules for rules:

1. Rules should be sufficiently clear, contextualized, and actionable that they obviously weren’t written by an idiot. Few rules pass this test. (I’m half-convinced that many writing rules were created by aliens as an experiment or a practical joke.)

2. Rules written for confused beginners should have both text and subtext that mean exactly what this audience will take them to mean. “Kill your darlings” is pro talk. Knock it off with the beginners.

3. Thou shalt write no rule that sounds like one of the Ten Commandments. They should be softened and brought down to a human level. Writing is a craft, not a cult.

4. Training wheels that should be unbolted as soon as one has found one’s own balance should be labeled as such.

I like these, Robert. 👍

Me, too, Robert.