“The world is a hellish place, and bad writing is destroying the quality of our suffering. It cheapens and degrades the human experience, when it should inspire and elevate.” — Tom Waits

By PJ Parrish

To be, or not to be? Nah, that’s too mundane for a novel. Even though it did work for Dr. Seuss. How about “exist?” That’s a nice variation. On second thought, it sounds too Descartes-desperate for a thriller. Sigh. Well, that leaves me with…”I live.” Good grief, as I live and breathe, why is it so hard to find the right verb?

You’d think this would be easy. Pick a noun, pick a verb. Repeat until you’ve written oh, about 300 pages that might resemble a novel.

But it’s not easy. Verbs are the lifeblood of what we do. The good ones juice up our writing and help readers connect with our plots and characters.

Here’s something I’ve found: Inexperienced writers tend to be content with the first verb that pops into their head. Heck, experienced writers, in the blind heat of the first draft, do this. (my go-to crutch verb is “turned.”) Often, when you’ve latched onto a dull verb, your subconscious writer mind knows it and desperately tacks on an adverb. “He said” becomes “he said sagaciously.” Lipstick on a verb-pig.

I’ve been thinking a lot about verbs this week. Partly, because I have been trying to brush up on my French via Babbel online courses. My brain aches because of this. Verbs are important to the French and they take their conjugations very seriously. One slip of the reflexive and you’re in deep merde. (More on that later).

But verbs are on my mind also because a friend, novelist Jim Fusilli, posted on Facebook a terrific article by music producer Tony Conniff called “In Praise of Bob Dylan’s Narrative Strategies…and His Verbs.”

Now, I am not a huge Dylan fan, but I do appreciate that he is a poet. (officially). And as I read Conniff’s analysis of the song “Tangled Up In Blue,” I understood how powerful the right verb in the right place can be. Take a look at just one verse of the song:

She was married when they first met

Soon to be divorced

He helped her out of a jam,

I guess, but he used a little too much forceThey drove that car as far as they could

Abandoned it out West

Split up on a dark sad night

Both agreeing it was bestShe turned around to look at him

As he was walkin’ away

She said this can’t be the end

“We’ll meet again someday on the avenue”Tangled up in blue.

Conniff says that most of the story is conveyed in vivid verbs — the action, drama, conflict and emotion. “The verbs tell the story,” he writes, “the story of how being with this other woman, probably for a one-night stand, led his thoughts back to the one he couldn’t forget or let go. Every verse, every chapter of the story, leads back to the same woman and the same impossible emotional place—Tangled Up In Blue.”

For my part, I love the title itself because in just four words and one great verb, Dylan captures the entire mood of his story. The man isn’t just upset about losing a woman. He’s not merely sad about an affair gone bad. He’s tangled up in blue, caught in a web of regret over the love he let slip away.

The right verb gives your story wings. The wrong verb keeps it grounded in the mundane.

Now here’s the caveat. (You know I always throw one out there.) Not every sentence you write needs a soaring verb. “Said,” as we’ve said over and over, is a supremely useful verb that, rightfully so, should just disappear into the backdrop of your dialogue. And in narrative, when you’re just moving characters through time and space, ordinary verbs like “walked,” “entered,” “looked” do the job. If you try to make every verb special, you can look pretentious and, well, like you’re trying to hard. Sometimes, smoking a cigar is just smoking a cigar.

Let me give you some examples off my bookshelf of verb-age that works:

Here’s the ending of Chester Himes’s short story “With Malice Toward None.” Himes’s verb choices convey the mood of a defeated man whose soul-killing WPA job is driving him to drink and to distance himself from his materialistic wife:

He wheeled out of the room and downstairs away from her voice but at the door he waited for her. “I’m sorry, baby, I — ” then he choked with remorse and turned blindly away.

All that day, copying old records down at city hall, half blind with a hangover and trembling visibly, he kept cursing something. He didn’t know what exactly it was and he thought it was a hell of a thing when a man had to curse something without knowing what it was.

This is from John D. MacDonald’s The Deep Blue Goodbye, showing how strong verbs can spice up your descriptions. McD didn’t give us much description but when he did it came with sweet economy.

Manhattan in August is a replay of the Great Plague of London. The dwindled throng of the afflicted shuffle the furnace streets, mouths sagging, waiting to keel over. Those still healthy duck from one air-conditioned oasis to the next, spending minimum time exposed to the rain of black death outside.

Verbs are important in action scenes. Here we are, in a good one from James W. Hall’s Off The Chart:

On the top rung of the rope ladder, Anne Bonny paused and found her breath. Head down, crouched below the gunwale, she gripped her Mac-10, formed a quick image of her next move, then sprang and tumbled over the rail, ducking a shoulder, slamming into the rough pebbled deck, and rolling once, twice, a third time until she came to rest against an iron wall.

I like the mix of mundane verbs like “paused” and “formed a quick image” next to the hyperactive verbs like “sprang” and “tumbled.”

And here’s a paragraph from SJ Rozan’s novel Absent Friends, where a character remembers the September 11 attack:

Phil had been caught in the cloud on September 11, running like hell with everyone else.

His eyes burned, his lungs were crazy for air. A woman next to him staggered so he reached out for her, caught her, forced her to keep going, warm blood seeping onto his arm from a slash down her back as he pulled her along, later carried her. Somewhere, someone in a uniform took her from him, bore her off someplace while someone else pressed an oxygen mask to his face. He breathed and breathed, and when he could speak, he asked about the woman, but no one knew.

The lesson here is, the more intense your scene, the more measured you should be in your verb choices. Trust the reader to intuit, to imagine between the lines. “Running like hell” is cliche but it works because it is true to Phil’s voice. It sounds like his thoughts. Notice, too, SJ’s repeated use of the ambiguous words — someplace, someone, somewhere — to capture the chaos, rather than hitting the reader over the head with something like: “He felt confused and disoriented.”

And let me add one more quick example that James Bell quoted here on Sunday, in his post about deep back story, from a Stephen King short story. One line jumped off the page for me:

Sometimes they discussed children puddling along the wet sand with the seats of their shorts and their bathing suits sagging.

God, that’s great. It’s not even a real verb, but can’t you just see those kids on the beach?

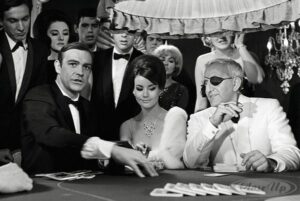

Okay, an exercise! Let’s use the poor old verb “walk” as a lesson here. Your character is a sophisticated spy entering the Casino de Monte-Carlo to meet the evil villain Emilio Largo. He’s not just walking in; it’s a grand entrance that sets up the next plot point. How do you describe this?

- He walked into the casino and paused when he spotted Largo at the baccarat table with his mistress Domino.

- He walked haughtily into the casino but then came to an abrupt stop when he saw Largo at the baccarat table. He had to take it slow, assess the man and the situation.

- He sauntered into the casino, like a king surveying his realm. But when he saw Largo at the baccarat able, he paused, and then ducked behind a palm and watched Largo, like panther eyeing his prey.

- He strode into the casino, but when he spotted Largo at the baccarat table, he slid behind a pillar so he could observe him without being seen.

I like No. 1 for its spare feel. It imparts only the bare choreography. You’d have to find other ways to convey the tension and the hero’s intent. No. 2 relies on a tacked-on adverb to convey Bond’s attitude. It works okay, imho. No. 3 is tone-deaf and over-wrought. “Sauntered” is an okay verb but way too twee for Bond. And then we get hit over the head with the king metaphor, made even worse by the panther nonsense. If your verbs are strong, you don’t need to surround them in a thicket of thorny metaphors. No. 4 works, imho, but I’d try to make it better on second draft.

I will leave you with one last thought about getting your verbs right. When I first started learning French, my teacher warned us that French is filled with faux amis — false friends. Some verbs look correct but become something entirely else if you mess up the pronunciation or use the wrong tense.

One day in class a guy, speaking in halting French, said that last night his girlfriend kissed him goodbye. Our teacher laughed and we all just looked at each other, confused. In French, a kiss is “un baiser.” So the guy assumed the right verb was “baisser.” Which correctly means that last night he was…screwed.

A sigh is just a sigh, But a kiss isn’t always just a kiss.

Great post. Turned is my go-to as well. I read a Lawrence Block article once and he used a McDonald example describing a walk-on character, a kid with braces. “He twanged the rubber band.” I don’t remember the rest of the example (it’s been over 30 years) but that part stuck with me and I could plainly see the kid.

I remember now…he twanged the rubber band with his tongue.

Well, that’s what I would call a genuinely memorable line. It stuck with you for 3 decades!

I read Jim Fusilli’s post and was immediately taken back to my UCLA dorm days, where I (like everyone in the 60s) attempted to play the guitar. My skills were only slightly better than my singing voice, but I remember the Bob Dylan Songbook and how the lyrics were all poetry. So thanks for the memories. (I might even still have that book.)

I agree with everything you pointed out, and your examples, so I’m not adding anything other than I take my “walks” and “looks” and fix them in edits rather than slowing down the writing. One of my former crit partners used to highlight all those “weaker” verbs, but sometimes they’re the right verb in the right place.

Yeah, re “weak” verbs. Maybe we should call them “functional” verbs. They are meant to just do some basic grunt work, right? If all your verbs are singing, how you gonna hear the arias?

Thanks for a great post. A lot to digest. (Would assimilate be better?)

Your stories learning French reminded me of a story my father told. After WWII, he visited France. A Frenchman, offended by my father’s butchering of the language, said, “You speak French like a Spanish cow.” Somehow, my siblings and I never became interested in studying the language.

Your discussion of verbs reminded me of a book I bought, but never read: “Vex, Hex, Smash, Smooch: Let Verbs Power Your Writing” by Constance Hale. I guess I should dust it off and study it.

Thanks for a great post.

HA! Vous parler Francais comme une vache Espanole! That is actually one of the first idioms I learned!

My other favorite is “J’ai une verre dan le nez.” I have a glass in my nose. It means you’re drunk as a skunk. Which is an interesting idiom in itself.

Good stuff, Kris. Re: “puddling” as a verb. On occasion I find myself doing that. Of course, the spell checker flags me. But if it sounds right (as it does in King’s example) I’ll keep it. If we writers cannot expand the language artfully, who can?

I’m with Jim on the “good stuff”, Kris. I just asked my wife (who comes from a French-first-language family) what “baisser” meant. She was doing a puzzle on her iPad and didn’t look up but just said, “something we don’t do much of anymore”.

{{{{rim shot}}}}

🙂

At a certain age, Garry, “(not) much of” is better than “not at all.”

A bit of blandness is okay because the offending verbs most often are stage directions for the reader– the character walks out of the room, etc., but blandness is death in action and emoton scenes. In other words, know which vocabulary battles you must fight.

Good way to think of useful bland verbs — stage directions. And as you say, save the fireworks for the hot scenes.

Thanks, Kris! Going into my file. My editor is keen on using those grunt verbs, and only getting fancy-schmancy a few times in a MS. She keeps me on my authorly toes.

Speaking of speaking French…I went to Vietnam in 2007, was there for two weeks on a medical mission team as a phlebotomist. I tried to learn some simple phrases to use with my patients, like “How are you feeling today?” or “Your little girl is so cute”.

Oh, the blank looks I got, the grins, the frowns. One of the team who spoke the language fluently told me I should probably not try. Vietnamese is very complicated…for instance, you can completely change the meaning by a tone lift or drop at the end of the sentence.

I tried to say good morning to an old man, and what I actually told him was the morning is on your teeth, or something like that.

And they say English is complicated… 🙂

LOLOL. Yeah, my nephew lives in Macau. He and his wife tried to learn Mandarin but were done in by the tone changes you mention. Their 10 year old daughter — no problems! Two things I wish I had started as a child — piano lessons and a second language!

And you editor sounds like a keeper.

I love invented words. Why shouldn’t we use our imaginations to improve the language? Lewis Carroll did it brilliantly.

When my husband and I traveled to Paris years ago, I thought it would be polite to use my smattering of French, so I glided up to the reception desk at the hotel and told the young lady in French that we had a reservation. She looked at me like I was an alien from another planet. I repeated my words. She repeated her stare. I decided this wasn’t working, so I opened my mouth to say it in English when my husband, who speaks no French, stepped up.

He used some combination of English and Italian (which he does speak) and added what sounded like a French accent to it. She looked at him like he was from another universe. Undeterred, he kept talking and gesturing in this made-up Frenglish-Italian mixture. Then a miracle happened. She nodded as if she understood. She even exchanged a few sentences. It was hilarious. We got our room key and chortled all the way up to the room.

I threw my touristy “French Phrases” book in the trash.

The French are, by nature, contrary. I think of them as cats to our American dog natures. And they are well, protective (is that the right word?) of their language. I have decent tourist French. But I have a god-awful accent, made worse by my natural Detroit twang. I’ve gotten laughed at, but I have always found it was appreciated when I tried. And you really know you’ve made a buddy in France when they begin to correct you. I guess that means you’re worth some effort. 🙂

Wow, such an outstanding post, Kris. I liked #4 the best. 🙂

My crutch verb is shrugged. Every single time I start reading the 1st draft from page one I’m dumbfounded as to why my characters are so shrug-y. Obviously, my subconscious sticks shrugged in the 1st draft on its own. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

When I was a young teen (13-15 yrs) I spoke fluent French in my sleep. ONLY in my sleep. Verified by my mother who studied the language in college. Not me. I took Spanish. Weird, right?

Gee, Kris…a bit of Waits, Dylan, MacDonald, King, Fleming, Rozan, Hall, and a whole lotta P.J. Parish…what’s not to love unconditionally here? Thanks for today’s thought poker.

Coining verbs is good. You can verb anything in English.

And, as a writer, discovering the right verb is often more satisfying than creating a good scene.

I even allow this to creep into my (gasp!) saidbookisms, especially in first-person narration, with verbs like “groused” and “grumped.”