By SUE COLETTA

Old English was originally written in the runic alphabet, named futhark after the first six runes: f, u, th, a, r, and k. The alphabet consisted of 24 letters, 18 consonants, and 6 vowels. Futhark assigned a sound to each character. Runes could be written in both directions—right to left, left to right—and could also be inverted or upside down. The earliest runes consisted almost entirely of straight lines, arranged singly or in combinations of two or more. Later, runes became more complex. Some even resemble modern day letters of the English alphabet.

Side note: Think outside the box as you read. There’s a question at the end to get your creative juices flowing.

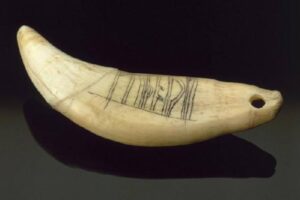

According to rune experts, the word “futhark” itself may have been used for ancient Norse magic. An example of this can be found carved into the tooth of a brown bear, found in Orkney in the 1930s. It’s said this amulet was used for protection or fertility magic.

In Old Norse the word “rune” means “letter,” “text,” or “inscription.” In old Germanic languages it means “mystery” or “secret.”

For years researchers have tried to crack a runic code called Jötunvillur, a perplexing code found in some inscriptions. Ancient codes prompt associations with treasure hunts and conspiracies as depicted in The Da Vinci Code.

But mysterious codes are not just for fiction.

Real-life Vikings and medieval Norse people carved runic codes into wood, stone, swords, pendants, and other objects. These codes are found in many forms and contexts.

“It was very common to use codes,” said Runologist Jonas Nordby from the University of Oslo. “Much of the population mastered them. That’s why I think they were something people picked up at the same time they learned the runic alphabet. If you had learned to read and write, you had also learned codes.”

Some of the decoded messages showed a playfulness among friends. Others were more romantic, like the 900-year-old cipher code carved into a piece of wood (pictured below). The inscription reads “kiss me.”

Photo credit: Jonas Nordby

These codes exist in many forms and contexts and date back to the 11th or 12th century. But there’s still a lot we don’t know about runes.

Why did Vikings encrypt their messages by using codes? Did they want to keep them secret, or did they have other reasons for encrypting their ruin texts?

Runologist K. Jonas Nordby has made significant progress toward an answer by cracking a code called jötunvillur, which has baffled linguists and historians for years.

Jötunvillur is just one of many different types of runes. This code works by exchanging the rune sign with the last sound in the rune’s name.

For example, the rune for “f” (pronounced fe) would be turned into an “e,” the rune for “u” (pronounced urr) would be “r,” and “k” (pronounced kaun) became “n.” Note: I put the last letter of the pronunciation in bold for clarity in deciphering the code.

Problem is, numerous runes end in the same sound.

“It’s like solving a riddle,” Nordby said. “After a while I started to see a pattern in what appeared to be meaningless combinations of runes.”

Many of the messages in runic codes include a challenge to the reader to crack the code, like “interpret these runes.” The art of writing and codebreaking ensured a certain amount of status among peers. Others bragged about their proficiencies, evident by the inscription below that reads, “These runes were carved by the most rune-literate man west of the sea.”

Photo credit: Bengt A. Lundberg/Riksantikvarieämbetet

“Many think the Vikings used cryptography to conceal secret messages,” Nordby continued. “But I think the codes were used in play and for learning runes, rather than to communicate.”

One of the reasons for his claim is that the jötunvillur code is written in a way that makes the interpretation ambiguous.

“A typical bunch of male adolescents were fooling around and wrote tall tales about treasures and their own sexual prowess. Jötunvillur can only be written, not read. It would be pointless to use it for messages.”

Hence why he’s considered other possible uses for the code. His best guess would be that the Vikings memorized rune names with the help of the jötunvillur code.

“We have little reason to believe that rune codes should hide sensitive messages. People often wrote short everyday messages. I think the codes were used in play and for learning runes, rather than to communicate.”

All runes have names, but their similar sound makes it difficult to figure out which runic letter the code refers to.

The rune codes weren’t just used for learning. Nordby says this also indicates whimsicality within the Viking Era and Middle Ages.

“People challenged one another with codes. It was a kind of competition in the art of rune making. This testifies to a playfulness with writing that we don’t see today.”

Nine of the 80 or so coded runic writings Nordby investigated are written in the jötunvillur code. The others are cipher runes written with the use of Caesar cipher, a system involving a shift to letters spaced a few places away in the alphabet. Researchers have understood cipher runes for some time.

Henrik Williams, a professor at Uppsala University’s Department of Scandinavian Languages and a Swedish expert on runes, said Nordby’s discovery is an important one.

“Above all, it helps us understand that there were more codes than we were aware of. Each runic inscription we interpret raises our hopes of soon being able to read more. This is pure detective work and each new method improves our chances.”

He agrees the codes could have been used as a tool for learning runes. But he’s not certain about how big a role jötunvillur played in the learning process. Rather, he thinks the codes were used for much more than communication.

“They challenged the reader, demonstrated skills, and testify to a joy in reading and writing.”

What better reason could there be?

Have you ever used codes in a story? Please explain.

Get those creative juices flowing, TKZers. In what ways could a writer use runic text?

This is so timely for me, Sue. I have two different projects going with secret codes in them. Loved this post.

Love when that happens! Staci, I’m so glad you commented today. You’ve been on my mind lately. Hope you’re okay. xo

When I taught at Copenhagen International School, I had lots of lessons on Vikings and Viking literature. I so wish I had known the information in this blog. Very interesting.

Thanks, Nancy. The course you taught sounds fascinating.

Regretfully someone else has co-opted Viking Runes

https://www.adl.org/education/references/hate-symbols/runic-writing-racist

Wow. I had no idea this was happening. It’s amazing how “some groups” can turn an ancient text into a racist symbol. Despicable. Thanks, Alan.

Sue, What a great article! As a former software developer, I wrote programs in code, which is just a way to organize all those bits and bytes, zeroes and ones, to create something of value. I love it — probably one of the reasons I’m attracted to mysteries and decided to write in that genre. Cryptic clues are really a form of code, aren’t they? And the detective’s job is to break the code.

In my novel, “The Watch on the Fencepost”, I use the Fibonacci sequence as the last clue in a series.

And you just gave me a great idea for a story. Thank you!

(The tooth of a brown bear in Orkney? That’s a mystery in itself.)

Lbz EjCjbodb (sorry. couldn’t help myself.)

The Fibonacci sequence as a clue in a series. That sounds like fun, Kay! Your skills as a software developer came in handy, I bet. 🙂 Yes, I agree. Cryptic clues do act as a form of code.

In my book, CASTLE KILLING, part of the storyline was Operation Gladio. This was a stay-behind secret organization in the 1950s that was supposed to prevent the spread of the Soviet Union. I wanted them to speak in a rare language so I picked

Guernésiais, the ancient language of Guernsey Island. I needed a language that was close to the European continent, that few people spoke, and that fit into a WW2 narrative. It’s also fun to through facts into mystery fiction.

Realism in fiction is important, IMO, Alec. CASTLE KILLING sounds cool. What a great way to include an ancient language.

Getting there. Thanks for asking.

❤️

Sorry. I hit “reply” to you, but the comment ended up on its own in the thread. Feel free to delete it.

No worries. ?

An interesting book on “The science of secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography” is The Code Book by Simon Singh. I found it particularly interesting on the development of the idea of using public and private keys.

Private and public keys for Onion sites? Wow. Adding to TBR. Thank you, Eric!

Well, here I am a day late (and a dollar short, as the saying goes…)

I have a WIP (let’s say a Stalled WIP), with an informal code used by Naval aviators during the Vietnam War call the Falcon Code – call signs and numbers for inside jokes and complaints and observations about the situation or chain of command… and some can be pretty profane (these are “sailors,” after all…)

A few of my (shareable) favorites include:

Falcon 139 – “I have a prostrate overpressure light” – i.e. gotta go to the little flyers room…

Falcon 143 – “It’s the Air Boss’s fault” – useful around the office…

Falcon 1000 – “Cool it, the boss is here” – same as above…

Any way, the premise is semi-comic (as the codes themselves are intended to be), dealing with the confusion that these are real, top secret codes and the stumbling/bumbling/fumbling attempts to steal and/or break them…

Hahaha. Love it, George! Get back to work on that WIP. ?

I used a kind of code, but it was an image within an image to let a specific person know help was on the way.

Sounds like a cool cryptic clue. Brava, Julie!