One of my biggest problems when writing is that I tend to get in my own way. This has occurred with some frequency during my latest project, currently titled The Lake Effect, which I discussed here a few weeks ago. You may or may not recall that I dreamt the beginning, middle, and ending of what is a love story. All that I have had to do is write the thing. This I am doing, and am having fun doing it. Occasionally, however, I can’t leave well enough alone. I know that I should simply tell the story. I’m doing that, but occasionally I seem to consider myself to be duty bound to insert into the narrative examples of how clever and knowledgeable I consider myself to be. As one might expect, I am usually wrong. The result is that my narrative bogs down. I’m not getting tripped up in detail. Sometimes one should stop and smell the roses, so long as the scent is pertinent in some way to the story. My mistake has been that I will be moving from Point A to Point B but will insist on stopping and describing Points A1, A2, and A3 along the way as well. I don’t consider my reader, who (hopefully) will want to get to Point B with all due and deliberate speed. I do this and wonder why it isn’t working, then realize that I am boring myself. If I am putting myself to sleep, then what am I doing to my poor reader, who will probably leave the building, never to return?

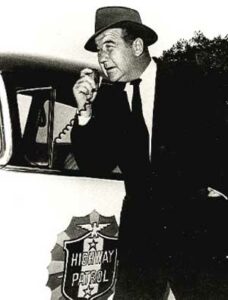

I have found that as a sort of enjoyable and tutorial penance for such a writing error I am best served by watching a few episodes of Highway Patrol. It was one of my favorite television series in the 1950s and remains so today. Each episode was about twenty-five minutes long. They would shoot the episodes in two to three days, twice per week, and broadcast close to forty episodes a season. This was done on a very limited budget. There were no fiery car crashes or extended shootouts through shopping malls. There were other constraints. Broderick Crawford was the lead actor. He played Dan Mathews, the taciturn, grizzled head of the unnamed Highway Patrol unit featured in the series. Crawford’s parts in each episode had to be shot in the morning because he was usually well-toasted by lunch. It somehow worked. Crawford delivered his dialog staccato-style (“Youshouldbesorryforwakin’meathishourwhaizzit?”) (“CorneraBrownanChocorantwoaclock”) (“21-50taheadquarters10-4”) when ordering his officers about. The cadence of Crawford’s diction, or lack thereof, was perfect for an episodic series where time was of the essence. There was also a formula applied to the shows which becomes obvious after a few different viewings. It was simple. A crime would be committed, Matthews and his team would chase their tales, and some evidence would be discovered, all within the first half of the episode. The last half of the episode (all twelve minutes or so) would show Mathews and his associates bringing the evildoers to justice. Voice-over narration by a gentleman named Art Gilmore gave each episode a quasi-documentary feel (“Burglary is the alley cat of crime, wandering the night in search of prey”). At the conclusion of each episode, Mathews, as he was getting into his car, would stop, look at the camera, and break the fourth wall by directly addressing the television audience with a pithy safe driving platitude, such as “It isn’t the car that kills…it’s the driver!” Just so.

Each episode of Highway Patrol was suspenseful and exciting even with such a cut and dry formula. Nothing ever really felt left out. Each minute — each second — was important. Highway Patrol was the first television series to utilize fast cutting — a few different action shots of just a couple of seconds’ duration (usually consisting of a police car racing to a crime, or chasing a suspect) — to move the action along. They also didn’t spend a lot of time getting the viewer from Point A to B. Mathews would get a lead, jump up from his chair and say, “Let’s go!” The next scene might show him driving quickly down a street for about two seconds (stock footage was often used, as Crawford at one point during the series run had his real-world driver’s license suspended for driving under the influence) followed by Mathews getting out of the car at his destination and shooting it out with the criminals. Bing bang boom.

If while writing you find yourself stuck in a thicket of your own design and wondering what to weed and what to water watch a few episodes of Highway Patrol. It is possible that you will absorb its lessons about narrative and storytelling by osmosis. All four glorious seasons (Crawford said the series stopped because they ran out of crimes) can be found on DVD, YouTube and a couple of cable channels. It works for me. If you already have a method of bringing your writing errors and ommissions on track, please share. And thank you. 1075 to 21-50. 10-4.

Thanks, Joe. Good message. And thanks for reminding (some of us) about Highway Patrol. I’ve got good–if rather vague by this time–memories of that show. I’ll have to check out some episodes on YouTube.

It’s interesting how some old shows still “work,” while other don’t. I’ve tried re-watching some episodes of Get Smart and wondered why I ever liked it. Maybe it’s the humor that doesn’t age well. I don’t think they attempted humor in Highway Patrol. I do still enjoy The Man from U.N.C.L.E.–but again, no humor.

Thank you, Eric. Other shows you might want to check out are M Squad (Lee Marvin! My Man!) and The Rifleman. All sorts of actors pop up on M Squad who later went on to big things and The Rifleman…you could put that on network television right now and it would kick posterior.

Good thoughts, Joe. I’ve learned a lot about pacing from watching certain TV shows over the years. But one of the more valuable lessons I learned about writing written (vs. viewed) stories ironically came from a successful screenwriter: “Remember, though, we ground the reader in the story with visuals and sounds. You have to work those into the story with words on the page.” So it remains a (wonderful) balancing act: everything moves the story forward while providing enough detail to keep the reader engaged.

Thank you, Steve, and thanks for sharing that great advice from the screenwriter. My favorite books tend to be those that unreel in my head in the same manner in which a movie would. I appreciate the reminder of the differences and similarities between films and books.

Good morning, Joe.

Great post. I tend to write with too little detail, not enough explanation, not enough sensory detail. Maybe some of that comes from working with an outline. Some of it may come from my day-time job where I’m constantly trying to cut through the clutter and get to the point. In any case, my best method for getting my errors and omissions on track are my beta readers, who are constantly asking for more detail.

Thanks for a great post.

Good morning, Steve, and thanks for your kind words and comments, particularly the reminder about the importance of beta readers. Those we have should be treated like gold. I doubt there are statistics on the topic but I would guess that many a book has been brought back on track thanks to a beta reader. Enjoy your weekend!

It was indeed the height of irony that a show about the Highway Patrol starred an actor who, at one time, was not allowed to drive himself to the set!

I do like seeing the L.A. locations of that era. When the show was in re-runs in the 60s, I used to crack my classmates up with a dead-on impression of Broderick Crawford. “We need more peanut butter and jelly at the lunch tables, now! 10-4.”

Jim, they also had an episode where they broke the bank and rented a helicopter. Crawford, while intoxicated, exited the copter and broke his ankle! They had to shoot around the ankle cast for the next few episodes and weren’t always successful.

I’ll have to arrange a meeting between you and a friend of mine who also does a dead-on impression of Crawford. You guys could recreate an episode. Or three! Thanks for sharing your memories.

Highway Patrol gave me one of the memorable lines of the 50s.

I don’t remember why, but Dan Mathews–no, I didn’t remember his name off the top of my head (I had to look it up in the IMDB)–had to have shot of something because of the disease they were encountering in the episode. While he’s talking into his microphone, the doctor, without warning, sticks him in his backside through his suit.

“Ah, doc. You using square needles?” he said.

Thanks for the memory.

Thanks for that, Jim! I remember that episode. I may have even used that line once or twice in the doctor’s office.

On a separate note, you remind me of something I was wondering the other day. Back in the day, I LOVED watching Emergency! and other such shows, where use of “10-4” was quite common. I still use 10-4 quite a bit as a short form of acknowledgement, even at work, yet I don’t think I ever hear anyone use it any more.

And I have wondered if any of the millenials even know what it means when I use it, though nobody has messaged back and said “What the heck?”

Thanks for the interesting question, BK! There are still quite a few jurisdictions which use 10-4, though many have gone over to “plain language” as a means of communication. I would imagine that it will take another generation or so to see whether 10-4 remains in the lexicon or goes the way of other terms, like, um, “please” and “thank you”…

I use the phrase a bunch, as, “10-4, Señor…”

Hey Joe, cut yourself some slack. You’ve only been on this story for a couple of weeks. You don’t need to expect perfection in a first draft. Just relax and write crap. You can always cut it later.

If you want to spend three pages describing a dandelion growing out of a crack in the sidewalk, go ahead. I find I often insert some totally irrelevant little detail in a first draft, fully expecting to cut it later. Then when I hit page 200, all of sudden that detail turns out to be important. I didn’t know it was needed but my subconscious did.

SPOILER WARNING: TV shows from this period had a very clear costume tell for the bad guys. The character who wasn’t perfectly dressed, his tie may be askew as an example, was always the bad guy. No wonder older people freaked out in the Sixties with those dang hippies.

Thank you, Marilynn! That explains why I can never get a window table at my favorite restaurants (except for Sonic).

I particularly enjoyed your comment today because in an episode of Highway Patrol I watched recently Dan Mathews walked around with his tie askew for the last half of the show!

I read an article by a TV historian several years ago on the subject. He used HIGHWAY PATROL and the first version of DRAGNET as his examples of how to spot a bad guy. Pay attention to see if he’s right.

Thanks, will do! 10-4!

I’ve been having this problem too–going off on tangents. I recently watched the first two episodes of Ozark. That show is great for action and tension in every single episode and almost every scene of every episode. It was a wake up call and I cut a LOT (but saved it in case there are places later in the novel where it might work).

First two seasons I meant.

Richelle, thanks for the reminder about Ozark, which over the course of two seasons has made me jump out of my chair more than a couple of times. Tension? One practically never knows what is going to happen from moment to moment. And it’s renewed for Season Three!