By PJ Parrish

I’m not a big ice cream eater. Take it or usually leave it. But the thing about living up here in Traverse Ctiy, Michigan, is that you must love ice cream. Not just any old Edys or everyday Haagen-Daz. It must be Moomers.

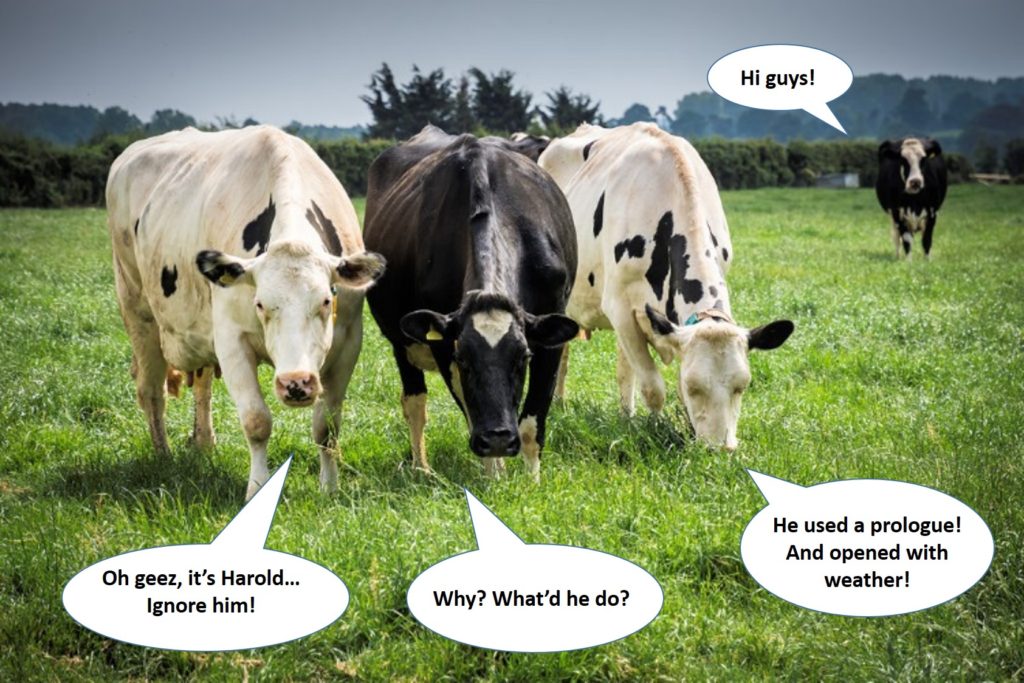

Moomers is a family dairy farm up here that has been around since the glaciers carved out the Great Lakes. Okay, I exaggerate. But Moomers is like dairy manna up here. Maybe it’s because the Moomer cows look so happy. You can watch them grazing as you snarf down your Cherries Moobalee ice cream from the parlor up on the hill. (see left) Recently I took my 9-year-old grand-niece to the farm and she asked me “Are those cows?” (She lives in Macau so doesn’t see a lot of livestock). I couldn’t help it. I said, “Those are sacred cows.”

Cheap joke. And this is a long way to get to my point. Moo-mer, me, okay? I’m having a bad week with the galley corrections, among other book stuff, and my brain is like mush.

So, let’s talk about sacred cows in writing. I’d bet you can rattle off a long list of them that you’ve heard in workshops, at conferences, stuff you’ve read in how-to-write books, absorbed from Stephen King, or even seen here at TKZ. Never use adverbs! Stay away from prologues! Write what you know! Write every day or die!

I dunno. Maybe it’s time to kill off some sacred cows. I’ll start. You guys can add your own.

Never Open With the Weather

I think this one started with Elmore Leonard. I respectfully disagree. Now, if you’re just painting pretty mood pictures on your first page with sunsets or trying to tell readers “bad stuff is coming” with rainclouds, yeah, I’d say you’re edging up to the cliche cliff. But if weather figures into your plot, go for it! In the aftermath of a hurricane, a man walking through the debris on a beach finds a baby skull. That’s the opening premise of our book Island of Bones, the catalyst of the case for Louis Kincaid. But we first had to show a woman so desperate to escape her killer that she ventured out into the fury of the hurricane in a dingy. Which brings me to the next cow…

Prologues Are Bad, Bad, Bad!

I don’t like prologues. I’m on record here with that. You know why? Most prologues are tacked on, like some flabby artificial limb, because 1. The writer couldn’t figure out how to establish world-building (common problem in fantasy) 2. It’s a giant info-dump about the protag’s background. 3. Writer panicked and thought he needed a wham-bam action opener as a hook because someone told him all novels have to open fast. 4. The writer is showing off and can’t stand to cut her beautiful prose. (Been there, done that.) Okay, here’s a rule you can take to the bank: Bad prologues are bad. I’ve read some great thrillers that open with prologues from the villain’s point of view and it works because it sets up the stakes for what the hero is up against. Also, some complex stories jump around in time or space and that can give the reader brain-cramps. And a good prologue can help that. Remember the movie Terminator? It opens with a great prologue.

Los Angeles, 2029: The machines rose from the ashes of the nuclear fire. Their war to exterminate mankind had raged for decades, but the final battle would not be fought in the future. It would be fought here, in our present. Tonight…

So you might need a prologue set in WWI and then you jump to chapter 1 present day. Maybe. But proceed with caution. Take off “Prologue” and sub in “Chapter 1.” Does it still work? Then ditch the prologue tag; the reader won’t miss it. Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land opens by telling us about a martian named Valentine. Then it jumps ahead 25 years. He labels the sections I and II, but to my mind, the Valentine “chapter” reads like a good prologue. Here’s a good post by agent Kristen Nelson on why most prologues don’t work.

Adverbs Are For Amateurs

“The road to hell is paved with adverbs,” Stephen King said sternly. What we’re talking about is mainly adverbs that end in “ly.” Many writers, especially when first starting out, struggle to find the right words to convey that beautiful chaos in their heads. So often we get stuff like: “You’re my world, baby-child,” she said lovingly. Or “I’m going to rip your head off,” he said menacingly. The problem, of course, is the dialogue should be doing the heavy lifting, and if you need a crutch-word after said, well, take a harder look at your dialogue. But every once in a while, you might need one for simple clarity. Don’t write: “He shut the door firmly” when you can say “He slammed the door.” BUT…I can make a case for “He closed the door softly behind him” or “Louis nodded thoughtfully.” So yeah, I think you can toss the occasional adverb into the stew. But as you gain more confidence in your writer’s voice, I’ll bet you use fewer “ly” words. She said encouragingly.

Show Don’t Tell!

I’m not going to try to kill this sacred cow (I believe in it too strongly). But I might try to tip it over. Telling is one of the hardest things to rid from your story. It’s also one of the hardest things to explain to new writers. I’ve devoted whole Powerpoint workshops to it. Basically, your story (and the reader’s experience of it) will be richer if it is filtered through the actions, words and thoughts of your characters. Simply put, you need to show your character doing things rather than you, the writer, telling the reader what is going on. Fiction is drama; not statement. BUT…to tip the cow, sometimes a little judicious telling is necessary. A novel is not a movie. Sometimes we can be “told” what is going on in a character’s psyche. And sometimes, we just need the clarity and shorthand that pure exposition can supply to move the story forward faster. “By the time he got to Phoenix, he was tired.” Maybe the journey wasn’t important, so this is all you need to tell. I think our own James pointed out here once that if you “show” everything, there is no modulation, and you end up giving equal weight to all scenes and actions. (Correct me if I’m misquoting you, Jim).

Write What You Know

This cow always kills me. Because if were true, all thirteen of my novels would be about an aging white woman whose biggest dream once was to be a hairdresser and who came THISCLOSE to being a housewife in the Detroit suburbs with at least three red-haired kids. (Don’t worry, I won’t explain that any further). I get where this hoary piece of advice came from: Don’t write about cultures, people, places or the kinds of stories that you have no affinity for. This is why I don’t attempt YA or sci-fi. But it does not mean you can’t write stories about opposite genders, different races, places you can’t get to physically. You are a writer! Your job is to make things up! See, there’s this wonderful thing in the writer’s chest called the imagination tool. I picture it as an awl drilling a hole into a different dimension. Writers live in this dimension of dreams (and nightmares), where things are easier, harsher, more beautiful, more terrifying, where we can be freer, more daring, than we can ever be in real life. If you ever feel disconnected from this power, go to a playground or beach and watch some kids play. They are unbound, they are passionate, they are making it up as they go along. Yes, you should use what is unique in your life experience for your fiction. But If you cannot tap into your imagination, if you cannot step outside your own skin and unleash your empathy, you can’t be a writer. I’ve lived inside the skins of six serial killers, a coma victim, a French-Algerian cop, a classical cellist, a fallen Catholic priest, a gay Palm Beach walker and a girl who believed she was a reincarnated slave. To say nothing of living for 20 years now in the skin of a biracial man. Louis Kincaid, c’est moi.

Okay, that was the liver and broccoli. Now let’s have some ice cream. Here are some “sacred cows” I found that I think are worth keeping around to graze in your brain:

Grab ’em by the throat and never let ’em go. — Billy Wilder

Develop craftsmanship through years of wide reading. — Annie Proulx

Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print. — George Orwell

Never get drunk outside your own house — Jack Kerouac

Leave out the parts readers tend to skip — Elmore Leonard

Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you are writing.– Henry Miller

When in doubt, bury someone alive. — Edgar Allan Poe

Okay, that last one is made-up. So what? So are all my books.

Can’t disagree with anything here, Kris. You’ve lifted my spirits this morning, thinking maybe I’ve learned something after all these years. As for the whole”write what you know” thing, I’ve always preferred “write what you can learn.” I am not going to have a nephrectomy just because a character needs one. (And why do people always ask about researching sex scenes but never murder scenes?)

Peripherally to that, I’ve been seeing a lot of discussion about #ownvoices and have to wonder whether it’s of any true value.

(And, my ‘save my info’ checkbox showed up again! Yay!)

So I am forced to use the Google machine before I even finish my coffee. 🙂 Was hesitant to look up nephretomy because it sounds so sinister. Whew.

As for The #OwnVoices. I need to look into this more. As I understand it, it is to support diversity among authors, rather than just diversity among the characters. But if someone here can talk intelligently about it, please chime in. This observation is purely anecdotal, but as Edgar banquet chair, I have noticed a significant change in the nominees in all categories away from the old white-man canon.

From what I’ve looked up, #ownvoices is a way to read about diverse characters through the experience of an author who’s in that minority. Like an autistic author writing about an autistic character. It’s for authenticity, and probably to keep everything from being “whitewashed.” but I agree with Terry on this. Being part of the “ownvoices” community, I find it very superficial. I think it is much more important to focus on diverse experiences and to dig deeper for the true emotions. For example, a white drug user would have more in common with a black drug user than a rich black kid. I know for a fact that the one and only character that I truly connected with is nothing like me. He’s male, he’s white, he can see, and he’s a pagan. Yet that’s the only time I ever felt a “yes, that is me, and it’s painful and exhilarating all at the same time.”

Fascinating. I understand the impulse behind #ownvoices, considering fiction has tended to be dominated by white male voices. This was a criticism I heard often about the Edgar nominations when I was on the MWA board. But to MWA’s credit, they made some significant changes in their system of picking judges and the process itself that I think has led to good things. But as I said above, I think the diversity begins at the publishing level and houses (esp smaller ones) are more attuned to minority voices.

As for what characters you identify with…funny how that goes. One character that really elicited a big “yes!” from me was Calliope in Jeffrey Eugenides “Middlesex.” She’s a hermaphrodite but her/his family dynamics really got to me.

Just read that a black American woman just won the Hugo award.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/aug/20/hugo-awards-women-nk-jemisin-wins-best-novel?CMP=share_btn_fb

I once heard we should never begin the first sentence of a book with dialogue. Not sure where that one came from, but if done right, it can hook the reader. I think some “sacred cows” probably came from frustrated writers who didn’t know how to properly kill them off. (Oh, gosh. I used an adverb!)

That’s a good one, Joan. It’s like prologues…if it’s good dialogue, then yeah, go for it! If it’s just characters flapping their gums, well, maybe there’s a better door to enter.

I love ice cream, but most ice cream shops & manufacturers STILL haven’t figured out the art of a super-duper mega-chocolatety ice cream. That’s why I concoct my own at home (not starting with the cow of course!) 😎

The surest way for anyone to turn me off as a learning writer is to inform me of their iron-clad list of absolutes. Of all the ones discussed above, the one that you could really put under that category would be leaving out the boring parts that readers like to skip, but frankly, you can’t even achieve that 100% of the time because no matter how well you write, there’s going to be someone that will yawn and move on.

I’m thankful that in recent years on blogs like these & other writer education media, there has been more effort to discuss these sacred cows less as the shaking-a-finger-in-your-face YOU MUST and more along the lines of a sanely argued, “most of the time, this is the way to go” strategy.

BK,

Yeah, I don’t really like the “leave out the boring parts” either because while it sounds cool, it can be taken the wrong way. Which leads writers to believe all description, interior monologues, mood and such should be stripped away. Elmore Leonard had a specific and very unique style. Whenever I read a book that tries to ape the style, all I hear is Leonard’s voice, not the writer’s.

I love using prologues, but only as a jump cut scene. IMO, it’s a great way to get the reader fearing for the character as the story rewinds in Chapter One. I also love ice cream. 🙂

Yup, I agree. That’s why we used one in the Island of Bones book, to show the victim in peril whose death is eventually tied to the baby skull found on the beach. But my memory is bad. I went back and look it up today. We actually labeled it Chapter 1. But it could have been called “Prologue.” Still, now that I think about it, it wasn’t a true prologue because the action was directly connected to the next chapter with only hours between.

Thank you for sharing another wealth of interesting points. It all comes down to what works, repeat, what works for the current story. However, before you break the rules, you must understand them and their purpose, then break them judiciously.

The section about leaving out the boring parts reminded me of the book, The Princess Bride. The author definitely left out the boring parts.

I *finally* got around to watching the movie The Princess Bride. What a joy it was. Maybe the book is as good?

It’s better, much, much better!

You forgot the sacred cow, “never start a story without ice cream.” I follow this one with diligent effort.

The balance you point out is key in my experience. Those cows moo in my ear as I write, reminding me to slow down and apply extra effort when the page action gets rolling at 90 mph. So often my mental adverb spotter helps me craft a much better phrase, or the show/tell bleat urges better imagery. Then the creative me hollers back, “Stet!” because some guideposts are just that, guides and not rules.

As usual, Kris, you timed this one perfectly for me. Nice going.

Ha…nothing like extending the metaphor, Dan. So now we don’t have a muse whispering in our ears. We have moo’s. (And a bleat when we go astray.)

Was discussing this very thing yesterday and had commented a few days ago on the KillZone that I’d read the “look inside” of many books recently and my estimate was 75% opened with the weather and 33% continued with the weather at the beginning of every paragraph and had absolutely nothing to do with the story. It was filler (more pages to turn, more KU money) so I’m with Elmore Leonard on this – if I pick up a book and it begins with the weather I put it back down again.

We all know about the road to hell and the “adverbs” but Anne Rice says in her “rules for writing” is to be generous with adjectives and adverbs because it “ads vibrancy”

So we see one well-known writer saying one thing whilst another says the opposite.

What I see as being said is, you have to write for yourself. Write the way you feel comfortable with and not because Stephen King said do it this way or Anne Rice said do it that way or James Patterson said “just pay someone else to write it for you” Rice, King, Brown and many many more became successful because of their unique VOICE (which JSB spoke of on Sunday in the KZ) we won’t ever attain uniqueness if we conform to the rules as stipulated by someone else. So the rules are all there and are there to be broken too – I just can’t go along with the opening of the weather reminds me of “Throw Mama from the Train” movie.

OMG….Throw Mama From the Train! I use that opening in my PPoint because it’s so damn funny.

“The night was moist…”

“The night was humid and wet…”

Here it is if you haven’t seen it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OLli0ua29dw

And yes, you are absolutely right. In the end, learn the rules then bend them to your writer’s will…that’s where style and voice comes from.

I have one firm rule: If it works keep it, if it doesn’t toss in a werewolf.

I realize, sadly, that some think not all stories need a werewolf. But when you’re stuck maybe you need a real shocker, so ask what is the worst possible thing that could happen to the MC right now? Do that. Note: You might have to go back and add a little foreshadowing.

I love ice cream, but that much sugar isn’t good for me.

Thank you for this great post.

Yes, add a werewolf….but only if his hair is perfect.

Warren Zevon, the Werewolves of London. I’m heading to Lee Ho Fook’s for a bowl of beef chow mein.

When reading writing advice, the first warning that the advice is bad is the statement that this is the only way to do this. Lots of people laud Stephen King’s ON WRITING, but he’s prone to such statements. Like, yeah, everyone instinctively knows how to structure a novel, and the plot, fully-formed, hops out of your brain onto your page like Athena out of Zeus’s head. No, Steve, no, it doesn’t except for the lucky few.

My comment to those rebellious types who think rules stiffle their creativity is that you must first understand the rule and why it is important, then decide why you will break it for a specific effect in your writing.

You’re right, of course. But when these ‘rules’ get in the way it’s time to re-examine them and not just bow before them.

You mentioned Steven Kings book on writing. While I found it a moving recounting of his problems, I didn’t get much else. I see Mr. King as a great seller of books, and he’s written a few wonderful books, but I don’t wait for his new releases.

Re rules: Yes, learn about them. But don’t get so hung up on them that they constipate you. One good thing King does say that I agree with is you should never write in a state of fear. Nothing good can come of that.

I agree with you. Stephen King wrote a memoir not a craft book. It even says it in the subtitle, but when first-time writers are told this is the best book on writing, what are they supposed to do. I was told that, and I remember wondering why I wasn’t learning anything from it. I decided I was just too different from every other other writer, and I had to go it alone. It wasn’t a happy thought, but it was the only thing I could think of. I didn’t even know the word “craft.”

On showing, not telling. The best example of telling being used well is in transitions. Something like, “Three hours later, they landed in Kansas City.” We don’t need to see the details of the flight–unless those details are important to the story.

Yup…thanks for the example. I blanked trying to come up with a simple one. Basic move-it-along plot stuff never needs to be shown. You do the business quickly and move on to the good stuff.

Which is why my airport/plane scene is only visible on my “cutting room floor” page on my website. But when I was starting out, the hardest words for me to write were, “By Friday, … “

Sometimes, a prologue IS necessary for world-building. I don’t mean distant worlds or fantasy worlds, I mean good ole worlds right here on earth. And in those worlds, sometimes, creatures that no one believes in–are told it’s unsophisticated, not cool, not scientifically acceptable–to believe in those creatures.

So, I’ve found, that an introduction of some kind may be necessary–make that REALLY necessary–to set up the process whereby a reader can suspend disbelief about them. To suspend disbelief in an animal or creature or being in present day America is not so hard for some, but apparently difficult for others. I had a strange conversation the other day with a millennial who believed in zombies, but not bigfoots, UFOs but not dogmen. He lives in a state where there are, as near as I can tell, no zombies, but there are plenty of UFO and dogmen sightings.

So how do I get him to sort of believe that he might run into a bigfoot if he ventures out into his neck of the forest far enough? I think perhaps telling a story–perhaps even (don’t boo) a long story–about how others may well have run into the creatures, describe what they do, how they smell, how they don’t dress, how thy frighten those who have had encounters with them may start the process. I admit, it must be an interesting story. And it will likely violate virtually all, perhaps with adverbs in the process, of the sacred cows discussed here today.

I sat down one day with an old Pima woman, a woman I’d known all of my life. I’d appeared in Christmas and Easter pageants and programs and plays she’d written for the platform of the little Presbyterian church she and her family attended. And she told me stories, wonderful stories, about the Pimas: why they live where they do, why Maricopas (a completely different tribe) came to live near the Pimas even in the present day, about their tribal stories and legends, about Etoi and the Trickster, about how the Lower Pimas felt about the Japanese peiople and Japanese-Americans who were relocated onto their reservation during World War II, about the Pimas in Mexico, about so many different things Pima. Oh, my, the stories.

You know what?

I used a prologue about prologues to bring you to the point where I could tell you about the stories and tales of my Pima friend. Would the effect on you have been different had I simply jumped into my account of the stories my friend told me? I don’t know. But I set the stage so that I could tell you about the visits I had with my friend. She is not longer physically with us, with me. She is still with me in memory and the remembrance of the stories she told me.

You know what else?

Before she told me her wonderful stories, she took a long time to tell me about the Pimas, where they came from, who they were in the distant corridors of time, who they are now because of those different corridors of time. Isn’t that called a prologue?

Yes, and what a great example. A well-rendered prologue — or as you call it introduction — can set the stage, make us eager with anticipation. One of my favorite books of all time is “The Mists of Avalon” by Marion Zimmer Bradley. (I’m into Arthurian stuff). It opens with an extended prologue by Morgan le Fey. She says, in so many words, “I am telling you all this so you will understand…” She is like a great storyteller, sitting you down, and saying, “Once upon a time, my brother Arthur lay dead and all the world changed. Let me tell you what happened.” It was enchanting.

I asked my agent a few months ago what is the real skinny on prologues. Are they really deal breakers? She sort of shivered and said that for established authors–those who have proven their ability to tell a good story well–there’s a suspension of doubt for prologues. But even for most of them, the prologues get cut and folded into the narrative in a different way.

In the case of first-timers, a prologue close to a deal-breaker because history has proven that in the vast, vast majority of submissions, it is a tell that the storytelling will be bad. If the very first word of your book raises a red flag, why take the chance?

Excellent point, John. Which is probably why I hammer away on prologues so much. It’s so hard to get a toehold these days, why do something that decreases your chances? Publishers are notoriously trend-bound. And if the word is prologues are dicey, why buck it if you’re just starting out? Because 9 times out of 10 you can cut it or just call it Chapter 1.

And never forget Ramond Chandler’s advise.

“In writing a novel, when in doubt, have two guys come through the door with guns.”

Yes!

But if one of those guys leaves a gun on the table in act 1 make sure someone uses it in act 3. (to badly paraphrase Chekhov)

Thanks for showing up today, TKZers. This is like a cool literary salon. Well, maybe not so high-brow as the Algonquin table, but stimulating as always. Nite!

Kris, well said! TKZ is like a cool literary salon and who needs high-brows?

Pingback: Author Inspiration and This Week’s Writing Links – Staci Troilo