My research for the Jonathan Grave series exposes me to some pretty cool stuff. Having never done the kind of work that Jonathan and his team do, the initial learning curve was pretty steep, and it will get steep again if I don’t stay current on tactics and technologies. A few weeks ago, I took a terrific class called Active Threat Response through Elite Shooting Sports in Manassas, Virginia. The focus of the class was on clearing rooms where bad guys are expected to be holed up. It was a Simunitions class, meaning that everybody had real guns that fired wicked little paint pellets that sting like crap when they hit. Instructors call that a “pain penalty” and I confess it adds real stress to simulated encounters. I learned a great deal during that class, and I thought I would combine those lessons with some others I’ve picked up over the years into a blog post.

They’re staples of every police drama:

As cruisers skid to a halt to confront a bad guy, cops throw their doors open and take a knee behind the sheet metal, using the panel for cover as they aim their weapons through the window opening. Maybe the officers in the car next to them will be aiming their weapons across the hood of their car.

Or:

The SWAT team makes its way down an apartment building’s cinder-block hallway to confront the barricaded bad guy. (All too often, the SWAT team is stacked up behind the plain-clothed detective who happens to be the star of the show–but that BS is for a different post). To prevent exposing themselves to return fire, they’re pressed up against the same wall that houses the door to the target apartment.

Or:

The good-hearted hero goes muzzle-to-muzzle with the bad guy, shouting, “Put it down or I’ll shoot!”

Well . . . no. We’ll take them in order.

A car door provides exactly zero reliable cover. Barring the off chance that incoming fire will hit one of the steel mechanical components inside the door, a full metal jacketed bullet will pass through a car door with relatively little loss in energy. And let’s not forget the exposed knees below the door and the exposed face and shoulders above the door. Not a good source of cover.

The guy aiming over the hood is in better shape tactically because he’s got the more-or-less impenetrable engine block as cover, but the exposed shoulders and face continue to be a problem. That problem is exacerbated by the risk of a poorly-aimed incoming round ricocheting off the surface of the hood and into his face. The smart move when using the engine block as cover is to peek around the wheel well and headlights while exposing as little of yourself as possible.

Before getting to the scenario of the guys in the hallway, I need to clarify that when it comes to SWAT tactics, there are as many procedure books as there are teams. Different teams clear buildings different ways, so the point here is to give you some things to think about.

All else being equal, an armed bad guy holed up in a room has a huge initial advantage over the team that’s coming in to get him. If the bad guy is willing to die as part of the transaction, his initial advantage is even greater. If there’s only one accessible door, the bad guy knows exactly where his attackers are coming from, and that gives him a free first shot.

Let’s say the hero cop in your story needs to clear a room on the right-hand side of the hallway. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll say the door is already open. If he approaches along the right-hand wall, he has zero visibility into the room until he’s right on top of it. Then, in order to do the job that needs to be done, he’s got to swing out and expose at least half of his body to whatever the villain has planned. That’s bad.

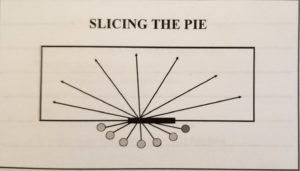

The smart move is to approach along the left-hand side of the hallway. As your hero approaches the open door, he moves with tiny steps, his weapon up and ready to shoot. As that plane of the doorway opens a little at a time, your good guy exposes only a tiny sliver of his body, a little at a time, and that exposed sliver is the one that holds a gun, ready to shoot first or shoot back. Incoming fire would require extraordinary marksmanship on the part of the bad guy. This tactic is call “slicing the pie,” and it’s more or less the same maneuver that would be used to turn a blind corner.

In general, it is always a bad idea to advance too closely to a solid wall surface like cinder block or concrete because of the risk of ricochet. By definition, ricochets have expended much of their energy on initial impact, but the closer you are to the point of impact, the worse the damage will be.

As for the muzzle-to-muzzle trope, I throw that in as a way to introduce the concept that a “fair fight” is anathema to every police and military agency I’m aware of. From the law enforcement officer’s point of view, the threat of overwhelming violence saves lives, but sometimes the threat becomes reality. No sane person who has the means to defend himself would try to out-talk a bullet.

“No sane person who has the means to defend himself would try to out-talk a bullet.”

I’m adding that one to a list I found that reminded me of your posts here at TKZ.

Entitled “Rules For A Gunfight by Drill Instructor Joe B. Fricks, USMC,” it includes one right on topic here:

“14. Use cover or concealment as much as possible, but remember, sheetrock walls and the like stop nothing but your pulse when bullets tear through them.”

I love Fricks’ rules.

Excellent post, John. Thanks for the useful information. Bookmarking this puppy.

Thanks so much. This post is a keeper.

As always, wow, another excellent post, John. I’ve taken to reposting a number of your posts to my writing group’s FB page. You just can’t fake steak. You help many writers get it right with your research. Bravo.

Great post, John, especially the illustration of slicing the pie. Seeing the diagram made the concept much clearer.

With ricochets, the bullet may lose penetrating power but, if it’s jacketed, the metal jacket can turn into shrapnel that still tears up flesh and muscle. Learned that from a guy who’d been hit in the belly after a bullet ricocheted off a rock.

He also told me another place to take cover on a car is behind the tire and wheel assembly. With so much plastic on today’s cars, the metal of the tire rim and brake mechanisms are more likely to stop a bullet. Only problem is, you gotta be pretty small to hide behind a tire and wheel.

Thanks for your always great info.

A couple of months ago, I was shooting steel targets at a police range with a buddy of mine. At 10 yards, I got hit in the leg with a ricochet. It was a tiny jacket fragment, but it hit with enough energy to pierce my denim jeans and draw blood on my leg. I’ve always been one to wear safety glasses on the range, but now I’m positively religious about it.

I knew it, I KNEW it! When Dear Husband and I watch cop shows, our conversation snippets are something like:

“The officers are too exposed.”

“The guys with the helmets and vests are standing BEHIND the detective.”

“If he shoots now, he’ll hit someone in the next apartment.”

Great post! And thanks for proving us right.:-)

Pingback: Writing Links 3/19/18 – Where Genres Collide