November 22, 2013, marked the 50th anniversary of one of my great research obsessions—the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Last name notwithstanding, I am of Irish Catholic heritage, and in my house growing up, the Pope and President Kennedy were held in equal esteem. When the news came that the president had been killed, my mother was devastated. I was six at the time, and while I couldn’t fully comprehend the enormity of the crime, I knew that Mom was upset and I found her grief unnerving.

November 22, 2013, marked the 50th anniversary of one of my great research obsessions—the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Last name notwithstanding, I am of Irish Catholic heritage, and in my house growing up, the Pope and President Kennedy were held in equal esteem. When the news came that the president had been killed, my mother was devastated. I was six at the time, and while I couldn’t fully comprehend the enormity of the crime, I knew that Mom was upset and I found her grief unnerving.

In the years that followed, Mom became quite the conspiracy theorist. She consumed all the books by Garrison and the others, and by extension, I likewise became a conspiracy theorist. By the time I was a senior in high school, I knew that there were at least two gunmen and as many as three. I steeped my geeky self in the research, even as I was penning stories on the side. (Look up “babe magnet” in the dictionary. My high school picture is there, labeled, “Not Him.”)

Once I got my acceptance letter to the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and I realized that freshmen had to write a major research project in their first semester, I knew that JFK’s murder would be my topic. Living in the suburbs of Washington, DC, and working a night job in telephone sales, I was in a perfect position to do primary research at the National Archives downtown. In the morning, I would take the bus to Constitution Avenue, and then I would head inside the massive Archives building to the reading room.

Once I got my acceptance letter to the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and I realized that freshmen had to write a major research project in their first semester, I knew that JFK’s murder would be my topic. Living in the suburbs of Washington, DC, and working a night job in telephone sales, I was in a perfect position to do primary research at the National Archives downtown. In the morning, I would take the bus to Constitution Avenue, and then I would head inside the massive Archives building to the reading room.

This was 1975. The Zapruder Film had still not been seen by anyone outside of official Washington, and the House Select Committee had not yet convened to re-examine the Warren Commission evidence. This was all new territory for me, and I hoped to forge new territory for my future professors.

Here’s how it worked: I would fill out a sheet of paper for what I wanted to look at, whether Warren Commission documents or FBI interviews, or re-enactment photographs, and then I would hand the sheet to a pretty young clerk-lady, and then she would bring my requests to me. It was table service, and as an 18-year-old with braces on my teeth, this was pretty heady stuff. They even called me Mr. Gilstrap. Very, very classy.

After four or five days of taking up space and making copious notes (no photos allowed, and certainly no copiers), I was sitting at my spot at a study table when the cart full of stuff I ordered arrived not with a pretty clerk at the helm, but rather it was pushed by an old guy.

“Mr. Gilstrap,” he said.

I thought I was in trouble. “Yes, sir.”

“You’ve been the source of a lot of curiosity here,” he said. He then went on to introduce himself as Marion Johnson, the curator of the JFK exhibit at the National Archives. He observed that they didn’t often see someone my age being such a dedicated researcher.

I explained to him about the paper I had to write, and about my family’s obsession with all things assassination-related. He seemed interested, and then he said, “Come with me. I think I have some items that you might be interested in.”

I followed him into the bowels of the old building, into a large locked storage room that was under-lit, and stacked floor to ceiling with boxes and file cabinets. “This is all of it,” Mr. Johnson explained. “This is our John F. Kennedy exhibit.”

I don’t remember the place itself well enough to give dimensions, and at the time, I didn’t have a frame of reference, but the room housed a lot of stuff. When he unlocked an area within the storage room that was set off from the rest by a chain link barrier, I knew I was in for something special. Mr. Johnson pulled a wooden case off of a shelf and placed it on a clear spot in an otherwise cluttered table. He donned a pair of cotton gloves and handed me another pair. When the snaps on the box opened and he lifted the cover of the box, I realized right away that I was looking at a Mannlicher-Carcano 6.5 millimeter rifle bearing the serial number C-2766.

“Can I hold it?” I asked.

“You can lift it,” he said. “That’s all.”

That was plenty. At age 18, I got to hold the rifle that killed John F. Kennedy.

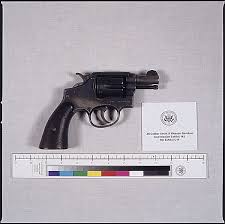

I noticed the .38 caliber pistol that was also in the box. “Is that the gun that killed Tippitt?” I asked. J.D. Tippitt was a Dallas police officer who Oswald shot to death shortly after the assassination.

“It is,” Mr. Johnson said. “But you can’t touch that one.” It seemed rude to ask why, and to this day, I don’t know.

“It is,” Mr. Johnson said. “But you can’t touch that one.” It seemed rude to ask why, and to this day, I don’t know.

From there, Mr. Johnson led me to a smaller room—a double room, really, with a few chairs on my side, and then a second room I was not allowed to enter that was separated from mine by a glass panel. It reminded me of the perp interview room in every cop show.

“Have a seat,” Mr. Johnson said. “You’re going to see something that very few others have seen.”

Within a minute, it became clear that the room on the other side of the glass was a projection booth. The lights dimmed, and then the screen on the far end came to life with the Zapruder film. Now that those few seconds documenting the fatal shots are so ubiquitous, it’s difficult to explain how thrilling—how heart-stoppingly shocking—it was to watch the events unfold in that little room. There’s no sound on the film, and there was no sound in the room—not even the clacking of the 8mm projector, thanks to the glass—as the motorcade swung the turn from Houston Street onto Elm, and then disappeared behind the traffic sign, where a still-unknown stranger opened his umbrella.

When the president’s limousine emerged from behind the sign, I watched his hands rise to his throat, just as they had in the countless stills I had seen of that moment. Jackie looked over, concerned, and then the top of the president’s head vaporized. Having by then seen stills of Frame 313 of the Zapruder film, I knew about the eruption of brain and bone, but those stills did not prepare me for the violence of it in real time.

I had held the gun that inflicted that wound.

I left the Archives impressed yet shaken that afternoon, and I was more fully emboldened to do my research the way it was supposed to be done. I stated above that I was a telephone salesman during the evenings, hawking Army Times magazine to people who loved to hang up on salesmen who sounded like they were eighteen years old. I hated that job, but it gave me access to a WATS Line, which was a huge deal back in the day—long distance phone calls to anywhere for very little cost. Extraordinarily little cost to me since I wasn’t paying for the service.

Abusing the largesse of my employer (who subsequently fired me, not that I cared), I was able to find and call the key players from the assassination at their homes, and like the staff at the National Archives, they were each impressed that someone my age would be so dedicated to a research project. Among the people I interviewed for that paper were Admiral J.J. Hume, USN (ret.), who performed JFK’s autopsy, Malcolm Perry, the Emergency Room physician who treated the president when he arrived at Parkland Memorial Hospital, and Cyril Wecht, MD, a forensic pathologist from Pittsburgh, who was a serious critic of the Warren Commission’s processes and conclusions. We’re talking long interviews, here, and not one of them ever lost patience with me—not even Admiral Hume, when I asked him what he thought about the accusations that he had botched the autopsy. His answer to that question, in fact, left an impression on me. He painted a picture of enormous pressure and emotion that I have later come to see as similar to the so-called fog of war. They were, after all, human, and the ravaged body of the president of the United States lay naked on a steel slab. I realized what a horrible moment that must have been for everyone in an official capacity.

By summer’s end in 1975, I had already made good progress on my paper. As I recall, it weighed in at something like thirty pages, and it contained photographs ordered from the National Archives, and the content of the multiple interviews that I had performed. When my mother read the paper, she was less than pleased by my conclusion that Oswald was the lone gunman—a conclusion I stand by today, and which has been reinforced by every bit of reliable new evidence that has since been released.

When I turned the paper in, I had no idea that it would nearly get me thrown out of college before I finished my first semester. My professor, Mr. Greene, as I recall, did not believe that a college freshman would do that level of research, and he called me in my dormitory to tell me that he was reporting me to the Honor Council. It took nearly three hours on the phone to convince him otherwise, defending every quote that I collected on my own, and every conclusion I drew.

In the end, I got an A.

Wow!

I was out of school for the semester, slicing cheese in a deli in Wayne, NJ. Everyone stopped when the Muzak stopped and the news of the shooting came over the speakers.

Maybe just a minute later, a voice came to me over the deli counter, “You gonna slice that cheese or not?”

* * *

Conspiracy theories are an interesting (and scary) phenomenon. Especially in this era of public lying and fake news. In this era of #pizzagate. I wonder if there are any good novels in which a conspiracy theory plays a key role.

Compelling novels with different takes from Mr. Gilstrap’s paper, varying treatment of Lee Harvey Oswald and conspiracy theory-motivated narratives include:

Dan DeLillo’s “Libra”

James Ellroy’s “American Tabloid”

Stephen Hunter’s “The Third Bullet”

I am sure there are others, but these are the ones I’ve read.

A fascinating and informative account –

thanks for sharing.

Wow. What you just described (spending hours and days lost in the researching) is what I call heaven. I literally could do that all day every single day if I was able (stupid day jobs!) 😎

It’s exciting just to read about it in passing on a blog so I know it is a memory of a lifetime for you.

Although I was never into the Kennedy assassination investigation stuff–but there was a reason. I took as much history as I was able in my college years, and one year, the professor started the semester with the announcement that we would have a research project. I was totally excited, until I found out that the professor had chosen the topic for me–you guessed it, the Kennedy assassination. I think this was about the time the Posner book “Case Closed” had come out. So all the wonderful subjects I was gleefully considering working on were squashed in favor of Kennedy. It smacked of the childhood era “Gifted and Talented” program where they recruited you into programs for your higher skills in language arts–but then chose for you what you would read (Shakespeare, etc. Yawn.). Needless to say, I didn’t last long in the program. I have always hated it when people choose my reading focus for me.

Here’s to reading, research, and following your passions!

I understand exactly what you’re saying. I learned early that in order to do a good job on a paper, I needed to choose a topic that interested me. In a first-year class in geography, we were given topics for our final paper – very basic topics, like deforestation, and such. I chose desertification. I live in Saskatchewan, Canada, which at times has desert-level amounts of precipitation, so I narrowed the focus to desertification in Saskatchewan. I wrote about farming practices, and how they often cause desertification, and how that can be offset by other practices. I got an A+ with a note that ‘this is too detailed a paper for a first-year class.’ But if I’d written the very basic paper she was expecting, I would’ve been bored to tears and it wouldn’t have been my best effort. I would probably have received a C.

Awesome story~!!!

…and an awesome title for an “alt history” novel~ the second gunman’s story…

Hmmmm… As I don’t have enough to do…

🙂

You know . . . that’s a really good idea for a book!

I was warmed by your description of you research times in the public archives. My Dad was a librarian, and I spent hundreds of hours doing research on various subjects and topics when I was a boy and on into high school and college. I have been given kudos for my research on how a young teenage girl born in Chengdu, China, would speak English if she suddenly came to the United States. It is included in my novel about Nokozjumi.

As to the Assassination, I will not argue with your conclusions, but I will tell you that I came to my own after reading Lifton’s book, Best Evidence. In that book, he is able to cite evidence that the wound on President’s Kennedy’s body grew by several millimeters between the time the Dr. Perry et al of Parkland Hospital made their initial examination, and when the body arrived at Bethesda.

Thanks for a great story about your research.

(By the way, my Dad worked for what was called the U.S. Indian Service in the 40s and before, and is now called the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. An Indian Service employee was killed during the Japanese invasion of Attu and Kiska, June 1942 to August, 1943. I am trying to find out his name.)

Thanks for the great story to open the day, John. And the rush of memories spent in libraries that it brought back. As much as I love the ease of computers, I do so miss that feeling of getting lost in time amid the stacks.

You certainly earned that ‘A.’

This is a post I won’t forget for quite a while. I can’t even imagine the magnitude, the sheer scope of what you encountered… holding that rifle and speaking to those people. Seeing a film so few had seen. Amazing.

As I get older, the story warms my heart more and more. Each of the people I talked to had every right to hang up on me, just as Mr. Johnson had every right to ignore me and stick to the duties of his day. Instead, each of them chose to show kindness to a kid they didn’t know. And yes, the impact was huge. Ever since, I do what I can to pay that forward.

A thought: I think this essay would provide the basis for a book on the matter–for example, how the research led you to the conclusion that there was only one shooter, despite the deluge of disagreement out there. I’d love to hear how you sifted the healthy and unhealthy ideas to come to your conclusion.

OMG, John, every paragraph literally gave me chills. I was twelve when JFK was murdered and very aware of the tectonic culture shift it caused. That was truly the day American innocence died and our national perception changed from hopeful to cynical.

With your ballistics expertise, I’m a bit surprised you concluded LHO was the lone gunman. Numerous studies of bullet paths and trajectories suggest at least two, probably three, triangulating from the Book Depository, grassy knoll, and even a storm drain that is no longer there.

Your diligence at eighteen is truly admirable. You captured evidence from direct witnesses who are now dead and forever unavailable to history. Incredible. I would love to read your report.

Thank you, John.

I wish I could find the research paper! I know it’s somewhere in the house–as is every story I’ve ever written–but our storage closets resemble that last scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

As for my conclusions, the biggest spotlight on a single shooter was the revelation a few years ago–ten?–that one detail not considered by most conspiracy theorists is the fact that Governor Connolly, who was riding in the jump seat in front of the president, sat several inches lower than the president, and quite a bit inboard of him. ABC aired a special quite some time ago (it might still be on YouTube) called “Beyond Conspiracy” in which forensics specialists meticulously reconstructed the shooting using autopsy data and synthetic cadavers (complete with clothing, skin, bones and viscera). Their results–shooting with an identical weapon from the height and distance of the School Book Depository–perfectly matched the conclusions of the Warren Commission, even down to the so-called magic bullet.

Every time I watch the Zapruder film and I see the fatal head shot, I’m baffled by how anyone can see the parietal spray as anything but an exit wound. (In fact, as I write this, I’m on my way to Ball State University to teach my ballistics course, among others, at the Midwest Writers Workshop, where JFK’s demise plays a significant part–thus, the motivation for posting this blog in the first place.)

Uh-oh. I’m feeling the pull of my geeky rabbit hole.

Thanks for the additional info, John!

You clearly belong down that rabbit hole b/c you’re pulling out vast stores of amazing material.

Mr. Gilstrap,

This blog has become so important to me that it is my first stop each morning. I’ve learned volumes, had my heart warmed, and my brain challenged. I’ve read the books of the contributors, including two of yours.

This morning I let my coffee go cold as I read today’s entry. Your essay is easily the most captivating entry I’ve read. Thank you.

Wow. That’s very kind. I appreciate your saying that.

Only an A? Not an A+++? Wow. That is NOT the level of research a freshman would usually do. Heck, I’ve known graduate students who were less diligent. Great job!

Living in Saskatchewan, Canada, I didn’t have the opportunity to do much primary research before the internet opened up access. Our provincial archives held microfilmed newspapers and land records, for the most part, which was great for genealogical research and which helped me get started on my current non-fiction research on a crime and trial which occurred in 1915/6. Our national archives, however, seemed completely out of reach way down in Ontario.

Recently, however, I was finally able to get the primary records for my research from the national archives, sent to me e-mail. It cost a pretty penny for them to photocopy all of them and put them into PDF, but it was cheaper than a trip to Ontario would have been. And I learned a LOT about the times, circumstances, and background of the case and trial. I also learned which of the ‘stories’ around the incident were true, which were false, and how the false ones might have been started. If I ever find another historical topic as interesting, I’ll start with the primary records.

What a remarkable story–loved every line of it. It’s clear you were hanging out with the wrong chicks! Then again, it’s probably good you weren’t distracted from your critical mission, right?

That rifle is most probably NOT the rifle that killed JFK. Anyone that mentions the magic bullet will also have to acknowledge that the 7 changes of direction of one bullet has NEVER been replicated.

I can’t teach you anything when you already teach ballistics, but we all know that conspiracies only survive because someone isn’t telling the truth, and people started disappearing once they disagreed with the official explanation.

The more interesting thing – than any conspiracy theory – is WHO actually had an interest in killing the one man that became an ICON for the office of the Presidency. Something we all miss as Trump has entered the White House.

Thanks for sharing John, that’s an amazing story. Certainly brings history alive to be able to touch LOH’s rifle.

Here, I thought I was being dilligent by keeping all my coloring books and comics in chronological order. And not mixing my crayon flavours.

You, John Gilstrap, are an inspiration.

Last night I watched the Lost Tapes documentary about the police recordings of that fateful day. This post makes an interesting counterpoint.

And it just goes to prove the power of research!