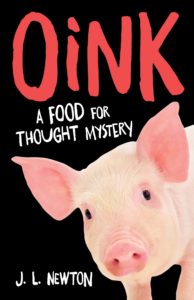

Please welcome Judith Newton to the TKZ. Today, her guest post is about raising social issues in cozies, based on her experiences writing Oink: A Food for Thought Mystery. I look forward to reading your comments and feedback! Clare

Raising Social Issues in the Cozy

by Judith Newton

I became interested in mystery sometime in the 1990s when I began reading Tony Hillerman, whose sleuths are two Navajo policemen. What I liked about Hillerman’s books was that they dealt with social issues—the ongoing colonization of Native peoples—and that they presented stories from the points of view of people on the margins. I was especially drawn to Hillerman in the 1990s because I saw myself as living on a different sort of margin at my university. I was director of women’s studies, the faculty of which I had worked to make half women of color, and I and my program had formed deep personal connections with faculty in the four ethnic studies programs.

This community building took place, however, just as a newly prominent national development (often referred to as “the corporatization of the university”) had begun to make our already marginal positions less secure. With its ever greater focus on profit, my university administration was threatening to defund our programs. In the end, I am happy to say, the administrations’ very efforts to do away with women’s and ethnic studies prompted the faculty in these programs to form an even more tightly-knit community and to fight successfully for our survival.

When I began to write Oink, I followed Hillerman in making my main characters people on the margins of the university, faculty in women’s and ethnic studies, but the biggest issue I faced in outlining the novel was how to write about their issues so that a general audience would want to read about them.. I was aware that puzzles and unsolved crimes keep people turning pages and that within different mystery genres there were additional inducements to reader engagement. Hillerman, of course, uses elements of the thriller. Guns booming in the dark always kept me reading. But I wanted a different feel for my novel, which would have a lot to say about the value of caring community both for our lives and for political resistance, so I turned to another genre, that of the cozy.

Cozies are characteristically set in a small and valued community. By making one of the most valued communities in Oink that of a political coalition I gave this convention a political twist. Many cozies also involve food and come with recipes. The presence of food usually affirms pleasurable connection among the characters, a connection that is then extended outward to the reader through the inclusion of recipes. In Oink the same is true, although there the major connections being affirmed are among those resisting the university’s turn toward competition, self-interest, and profit. The inclusion of recipes pleasurably invites the reader into this alliance.

In Oink, moreover, as in the history on which it was based, gathering around food is one manifestation of a larger organizing impulse based upon “working on the relationship” through multiple acts of friendship, love, and support. This is a strategy which black women had already employed to organize grassroots communities during the Civil Rights Movement and it reappears in Oink among the women characters in particular.

The cozy’s quirky, often, female sleuth and its characteristic humor are also present in Oink and serve a related purpose. According to J. K. Gibson-Graham, our repertory of tactics for getting people together should include playfulness and humor, which can toss us on to the terrain of new possibilities. By fusing playfulness and humor with a story of struggle, I aimed to attach a sense of optimism and possibility to political resistance.

By merging Hillerman’s focus on social issues and marginal points of view with the conventions of the cozy I could write about some of the difficulties for people on the margins in the university and in the nation while also immersing the reader in experiences of connectedness, love, humor, and pleasure, experiences which I hope will keep the reader reading and which I identify both as ways to live a more fully human life and as crucial to effective struggles for social change. In a way I hadn’t anticipated, the continuation of these values seems ever more critical to our time.

- What do you see as the advantages of or the difficulties in using cozies or other kinds of mystery to address social issues?

- Are there particular cozies with a social issue or political theme you have read and enjoyed?

- Does exploring social issues even belong in a cozy?

This sounds like an intriguing idea. I don’t see why you can’t address social issues in a cosy mystery – so long as you don’t beat people over the head with it. I can’t tell you how many issues I’ve started to notice only after reading a novel where they appear in the background.

Humans are wired to respond to story rather than bare fact. Putting social issues in the background of novels sounds like a great plan, especially if those issues are relevant to the plot.

In my regular genre – I’m a romance writer who reads TKZ for the brilliant writing lessons (please don’t all run away at once) – this happens a lot. In the foreground boy meets girl etc. In the background, all kinds of other themes are handled.

Hi Rhoda, Thanks for writing. My initial answer to you disappeared but is contained in some of my other comments. I so agree about being our being wired to story. Though writers often plot in a way that brings home their emotional response to social issues. Ie, Dickens begins with random characters, suggesting the indifference of people to each other, and then ends up showing how all those characters, including the high and mighty, cannot escape being connected and affected by the lowly.

“connected to and affected by” that should be.

Thank you for this post.

I offer my gratitude even though I am about to strongly disagree with most of what you implied. Given how TKZ tends to shy way from politics, I won’t mention neither my views on the academic field of women’s studies nor my aversion for the sheer lunacy of most of contemporary identity politics.

On topic, though, using fiction as a camouflaged delivery vessel for the author’s political convictions is a misuse of the art. It reminds me of conceptual art, which is often nothing more than a proxy for the author to vent politically, sociologically, anthropologically, but not aesthetically, mind you, while at the same time eschewing the intelectual responsibilities that would burden him had he chosen to do so, say, in a magazine article. If a novel’s takeaway is that women are oppressed, ethnic minorities are oppressed, homosexuals are oppressed, transgender people are oppressed, the writer is not expected to substantiate his claims. If, however, the same writer were to make those very same claims in a peer-reviewed academic paper, then he would be forced to define «oppression» and present hard data to back up his assertions. It’s not difficult to see then why so many would prefer fiction over academia.

I have brought the rather paradigmatic example of videogames before and think the media illustrates perfectly the pernicious influence of Social Justice Warriors on authorship. These people can’t seem to fathom the basic distinction between ideology and fiction. Case in point, Mass Effect Andromeda, by Bioware, a videogame company that prides themselves on going with what they would deem strong female protagonists, on diversity, on inclusiveness, on having a plethora of sexual orientations on display, ticks all of those boxes and yet, nonetheless, remains a ghastly piece of bad writing. In the cast of characters, they’ve included the mandatory female lead, the mandatory gay team member, the mandatory transgender crew member, and so on, and despite all of that, or, more precisely, with the help of that spurious and cardboard intrusion of ideology on fiction, the end result is nothing short of inane.

Tread consciously and judiciously when it comes to tackling social issues in a piece of fiction.

That’s my take.

To NR, I completely disagree with this:

“On topic, though, using fiction as a camouflaged delivery vessel for the author’s political convictions is a misuse of the art. It reminds me of conceptual art, which is often nothing more than a proxy for the author to vent politically, sociologically, anthropologically, but not aesthetically, mind you, while at the same time eschewing the intelectual [sic] responsibilities that would burden him had he chosen to do so, say, in a magazine article.”

Hello The Color Purple. Hello 1984.

Even Song of Solomon , a required reading in my day of middle school, had implications of deep rooted literary genius, but on the surface, read like trash (my opinion). You can’t say that “using fiction as a camouflaged delivery vessel for the author’s political convictions” is a misuse of art, because art is not based in the intellectual thought of other artists, it is based in creative expression of the artist and the interpretation and perspective of his audience. How does one misuse creative expression? An audience decides the relevance of creative expression, not another artist, who might be otherwise bias in some way.

Take Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil as another example set in the local cozy town of Savannah, GA. A crime takes place there and it’s based in non-fiction and the tale covers many characters from the town local male prostitute to affluent socialites and even a transgender woman.

So, for these reasons, I disagree. I believe there is a place for using fiction and creative non-fiction to craft stories that resonate with readers all over the world.

Thanks.

And I completely disagree back at you. 🙂

I’m inclined to believe we fundamentally disagree on the nature of art and that our disagreements will thus never be solved, which is unimportant, anyway.

We seem to disagree on what the ontology, not the phenomenology, of art is. If I submit an inverted urinol and call it “fountain” and proclaim it to be art, that in and of itself does not render it art. Duchamp knew this exceedingly well, even as he indulged in an exercise in mockery of the status quo. Mockery was taken seriously by people lacking a sense of humour.

If you’re by any chance interested, I have expanded a little bit bellow in a second post.

Cheers!

Yes, hello 1984 and Animal Farm and the hilarious Dear Committee Members for a more modern example.

My concluding remarks:

The irony here is that for every Dickens and Orwell and jazz singer Abbey Lincoln invoked I would be able to counter-offer Celine and the Russian Constructivists and the Italian Futurists. The 20th century documents the failure of art as successful mean of radical social change, which, of course, says very little about the artistic merit of the works themselves. That door swings both ways.

Fiction processes life, and life includes everything, from dandruff problems to world politics to cosmogony, and everything in between. Author sovereignty is absolute. He should do as he pleases, write about whatever he feels like with disregard for what others deem acceptable. That’s sacred ground. But should he put ideology first, in a way that trumps and conflicts with the principles of fiction and the story’s internal logic, his failure will be very apparent to the readers.

If you think accusations of racism, sexism and xenophobia aren’t being wielded against authors of works of fiction, you might want to follow the videogame industry more closely, where they are a staple in some niches associated with the SJW movement.

Regardless, it was a real pleasure engaging with you and I do hope to read more from you here on the TKZ.

I don’t think we’re really disagreeing here. Art might not be successful at “radical social change,” but it can affect our views of the world and sometimes for the good. If the writer ‘s ideology or politics aren’t conveyed in a good story, then the failure will be obvious. Analyses of racism and sexism in works of fiction and video games are often made, sometimes with complexity, nuance, and justification, other times, without. Always go for the complexity, I say. And thanks for this interchange.

I agree that one always wants to proceed consciously and judiciously. Being an erstwhile Victorianist, however, I am accustomed to writers who wrote fiction because they wanted to deal with the social issues of the age. I’m thinking Dickens, George Eliot, Bronte, and Jane Austen too. Their political convictions were very much in evidence. Dickens hated the harsh treatment of the poor, Bronte wrote in partial rebellion against the limitations placed on women. They were great story tellers and they consciously wrote about social issues. I would never say that dealing with social issues in a conscious way necessarily makes for good writing (I’m addressing your point about the video game) but it doesn’t necessarily produce bad writing either. I offer Dickens once again. Thanks for writing.

I’m writing a story based on a disturbing pattern of abductions, where young dreamer immigrants disappear. My Mercer’s War (vigilante justice) series.

I chose innocent teens & young college students as victims to draw the reader into their plight. One victim goes missing after she’s traumatised by a deportation force arresting her parents & deporting them, making her alone & vulnerable.

It’s important to put a face on the problem & key on the emotional stakes. I plan on presenting the facts of the storyline without a message, allowing readers to make their own judgments. I’ll ramp up the stakes by adding a conspiracy of a “what if” scenario based on newspaper headlines & our social climate today. Again, no preaching, but I hope to get readers intrigued by the mystery/suspense of the conspiracy, while rooting for innocent kids to be saved by my hero & his covert team of vigilantes.

Hi Jordan, This sounds like a good plan. It’s the kind of conscious consideration of form that I was trying to write about. It was no accident that Dickens began Our Mutual Friend and many of his other novels with a scattering of people who seemed to have no connection to each other in order to have them end up completely bound up with each other’s lives by the end of the novel, hence demonstrating that we are all connected.

I agree. If books don’t reflect our times, then they may turn out to be too generic and forgettable. My books tend to feel as if they were ripped from the headlines. I have to trust my gut as to how those headlines manifest. Thanks for the thought provoking post and welcome to TKZ.

Writing historical mysteries I find it almost impossible to shy away from social issues since they provide a much needed backdrop to the story – that’s not to say I have any particular political message or motivation when I start writing, only that political, economic and social issues that define an era cannot be ignored. As I usually have female protagonists, the role of women during that period of history also comes to the fore. I think mysteries in general provide a great framework for exploring all sorts of social issues – kind of goes hand in hand with crime – but I do agree that you have to be judicious in how you approach these issues. Most readers do not want an author to get up on a soapbox but appreciate an examination of issues as they pertain and deepen the story. Thanks for the blog post, Judith!

Thank you for writing, Clare. Yes, hard to write historical fiction without a firm grasp on what the period would have expected from female protagonists (even if they rebel against those expectations. Hello, Jane Eyre.)

Social issues, as a part of real life, belong in any genre. Whether as a major part of the story (because a lot of conflicts are social in origin) or as part of the environment behind the plot, social issues really can’t be avoided without creating bland characters, bland setting, bland conflict. Even if one were to create an elite world populated solely by rich, straight, white, healthy people, conflict would have to come from somewhere. In such a world, that conflict would probably be based on greed of some form. Perhaps romance (which always brings in a conversation on gender balance, no matter which side of the equation you’re on). Perhaps competition or politics. And any one of these would involve some social issue, from one side or the other. Greed, itself, is the basis of many social issues. If you want a realistic fiction, if you want a believable fiction with believable conflict, social issues must be considered.

What I like about fiction is that it can discuss social issues without being blatant about it. It can show the current situation, the current and future (or past) results of social issues… and it can have a deeper effect than anything more blatant. I write science fiction and fantasy, so forgive me if my examples are in that range. In the 1960s, Star Trek brought a lot of social issues to the fore, causing some disturbance with the first television interracial kiss, and many other firsts. But what it did most subtly was it had a black woman as a very efficient officer on the bridge of a huge battle-ready space ship. Her very presence had an impact on television and on society. People could see that she was as capable as any of the men on the bridge. It became more ‘normal’ to see a black woman as a capable person.

Normalization is an important part of social change. I used to work for a cancer-related organization, and one of their goals was the de-normalization of tobacco use. (Yes, I know, there are people against this, too. But scientific fact is: tobacco causes cancer, and cancer kills.) De-normalizing tobacco use would make young people less likely to start smoking and non-smokers less likely to have to live in a cancerous cloud of other people’s smoke. De-normalizing smoking makes it socially less desirable.

My point is, social issues are a part of life. Social change is most likely to be brought on by normalization. In fiction, one can show a new normal, a different normal, and have it become accepted. This is where fiction is most valuable – it can work on a person’s thoughts and insights behind the consciousness. People’s opinions change without them realizing it.

Thank you for writing BJ. And, once again, Eliot very consciously wanted to change people’s thoughts, wanted to instill a sense of the importance of striving for social change even though life for women in particular was a “middle march,” in which change was slow. and sometimes almost imperceptible.

When ideology – which, surprise!, in its own mind *always* has the best of intentions – trumps fiction’s internal logic novels tend to go sideways. A writer shouldn’t have his characters indulge in a drag in order to help “de-normalize” smoking habits? Wait, really? Even though those characters’ background and culture would otherwise have be avid smokers, the author should force his own hand and rewrite the whole thing just so it’ll more closely resemble a NHS pamphlet, really?

And where, exactly, does the purge stop?

Should we irradiate violence from fiction in order to “de-normalize” violence? Should we never ever have impolite characters, just so civility is heralded and advanced in society at large? No theft, no murder, no non-consensual sex, no lying or coveting either, and soon and sure enough you’ll have extinguished all life out of every single printed word.

This notion that “de-normalization” in fiction helps to choke down what is deemed by some as undesirable behaviour is highly questionable and the smirking me is reminded of the case of soft drug consumption among youngsters in that regard. The problem is the same: viewing fictional work through the prism of ideology is a failed project at both ends, when you’re creating it and when you’re reading it. One of the major faculties of a writer is his ability to understand and even empathize with people he would despise in real life. Good writers present the obnoxious character’s case convincingly, as opposed to moralizing or omitting the unpleasant and the frowned upon for the sake of political correctness. The idea of “de-normalization” runs absolutely contrary to that.

Authors who, for example, happen to portray submissive female characters are not necessarily sexists in real life nor advocating sexism in real life, authors who include ostensibly flawed members of ethnical minorities in their casts are not necessarily racists nor advocating racism in real life, nor are they misrepresenting entire ethnical groups in a unfavourable light.

To suggest otherwise would be disingenuous.

I don’t think anyone is suggesting what you say in the last line. But “de-normalization” is very common in some great literature. Sorry to use Dickens again, but his work very consciously tries to de-normalize indifference to the suffering of the poor. A good deal of great work by black writers does something similar around the historical suffering of black people. It tries to de-normalize the indifference of white readers.

NR, you have a rather odd view of normalization. Normalization (and its counterpart, de-normalization) is not about ‘irradicating’ anything. ‘Normal’ is a societal construct. In the 1950s, for instance, ‘normal’ was the husband working outside of the house while the wife kept a clean house and watched the children. That ‘normal’ changed as more women entered the workforce and as wages decreased relative to cost of living. Today, not many families can survive financially and remain in the same social class without both adults working. Today’s normal is two working parents/partners. Does that mean that there aren’t single income families? No. But it’s not ‘normal’ according to society today.

In the 1950s, normal offices were full of white husbands putting in their hours to take money home to their white housekeeping wives. Today, you’ll find very few offices that are full of only white men. Today’s normal is a multicultural workforce of men and women. Does that mean there are no white men working? No. Does it mean every office in North America is multicultural? No. But that is no longer normal. People are more likely to consider non-multicultural offices to be different. Multiculturalism is today’s normal.

I look forward to the day when non-smokers (who have always been the majority) are considered normal, and it is no longer normal for a young person to start smoking.

I would never suggest authors refrain from casting any character in a negative light. All character flaws are welcome, even if they are stereotypical or generalized. If we were to go back to the cozy and influence of food and culture, we would find that these things are a necessary component to globally appeal to wider audiences.

I was given a complimentary copy of Ignorance Ain’t Got No Shame, by Tracy Lenore Jackson, and I was surprised at how well I took to this memoir of a black woman struggling through life and addiction. I couldn’t relate to the corn bread and milk or the flat ironing of hair with coco butter, but I was deeply immersed in the story because it put me in the culture and rang true, even though I never experienced that culture.

I also encourage writers to not tip toe around social issues or political correctness. To me, stories which are unencumbered by such frivolous nonsense are much more appealing and satisfying.

On the same note, many of the literary classics are filled with political statements and they’ve successfully been that vehicle to promote awareness about social and political strife. To Kill a Mockingbird, Pride and Prejudice, and Of Mice and Men all had social and political undertones and were brilliantly written I think.

My thoughts on racism and sexism in fiction writing

To assert that either one addresses a social issue and inevitably fails as a story-teller OR one eschews social issues as the only way to create a “true” work of fiction–that is a false dichotomy.

The story must come first, but that does not mean one cannot infuse a bit of social issue into it, nor does including such issues inevitably mean a work more concerned with social engineering and correctness than telling a good story. However, it’s critical for the writer who infuses a social issue into his/her work to be aware of the danger of falling into a polemic.

Hi Rick. Yes I completely agree with this, though some satiric novels and even Dickens at times become polemical, Dickens with sometimes thrilling effect. But few of us are Dickens.

I think I agree with both of you. 1984 is an excellent example of what I mean. Orwell showed us the pain. He didn’t hold forth with a colorful diatribe on the evils of a dictatorial government. I agree about having the stereotypical characters would be simplistic, but I think seeing how this situation effected their lives could be fascinating. How it made one of them into a murderer. Done well, this could be great.

If I may, and, here I am again, a day late (but hopefully not short the proverbial dollar), I’d have to say the “undercurrent” of social setting or commentary can frame the story, but shouldn’t bludgeon the reader with ITS message ~ the oft referenced 1984 as an example.

CJ Box uses this (usually) to good effect in his Joe Pickett series, working with sometimes controversial current movements as the instigators of the mystery ~ environmental terrorists, survivalists, government overreach ~ as the background in front of which his characters act.

As in songwriting, few want preachy entertainment, though as shown by artists as varied as Dylan and Johnny Cash as Bruuuce and Woody Guthrie, it is possible.

I write mysteries specifically for the LGBT market and for lesbians, in particular. I’m a member of the community myself. My life, all of our lives within the LGBT community, are walking, talking, living, breathing social issues. Our literature and our stories typically reflect that.

I spun a cozy mystery series off my lesfic mystery series. It features the mothers of my two lesbian protagonists in the other series. The two younger women do, understandably, make appearances in the cozies. Mainstream readers haven’t had much to say about that. I’ve had lots of crossover lesfic readers to the 2nd series. Now I’m starting to see some mainstream cozy readers drifting toward the original, now 9 books strong, series that has a permafree first in the series book drawing them.

I’m getting a little pushback from more mainstream readers over the content of the lesfic series which, at every outlet, is clearly categorized as lesbian themed first and mystery (women sleuths usually) second. A few have lamented that the stories were good but they didn’t see why the characters ‘had to be gay.’ Others are much more vocal. They say they liked the story or stories but they could have done without female/female sex, etc. Some read one or two of the books but then go on record to say they won’t read more because of the ‘themes’.

I understand not shoving social issues down people’s throats. On the other hand, mainstream readers who gravitate toward niche fiction written with a particular audience in mind should understand that they’re going to get something quite a bit different from homogenized, mainstream fiction; something that maybe challenges their world view, whether the author intended it to or not. It wasn’t written for them. If they insist on reading it, for whatever reason, they should at least come into it with an open mind.