Ah yes, it’s in the air. Happens every December. All that joyous warbling. All that frantic pushing and shoving. All that delicious anticipation that leads up to that frenzied moment when you tear off the wrappings to get that lovely prize.

Yes, it’s the annual Bad Sex In Fiction Awards.

Don’t know about you, but this is the highlight of my year as a writer. Because I have been there, naked before the computer screen — well not literally but quite figuratively –- trying to put into words this most basic human act. And it is not easy to do without sounding like a fifth grader with a gland disorder.

Yes, I have sex. In my books. But I usually weasel out and fade to black, hoping my readers are old enough to remember when Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr rolling in the surf was hot. And I have sat on enough sex panels at writers conventions to know that all my fellow authors struggle with this. Except maybe Barry Eisler but I once saw him take down a drunk in the bar at the Edgars so maybe his id is a little more out there than the rest of ours.

We crime dogs all know one truth about our genre: It is far easier to write the most evil serial killer than it is to write about the two-backed beast. And I, for one, really appreciate the fact that the editors at the Literary Review wade through all the big important novels to cull out the best examples of the worst sex committed on paper. Because I like knowing that people like Phillip Roth and Tom Wolfe can, when they really apply themselves, write worse crap than I can.

The bad sex prize was established by the Literary Review “to draw attention to the crude and often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel and to discourage it”. There were so many good entries this year that even J. K. Rowling (The Casual Vacancy) and E.L. James (Fifty Shades of Gray) got nosed out.

So…do you want to read some excerpts from the finalists? I warn you, this is not for children or those with weak stomachs. Go ahead. Read ‘em. You know you want to. But you’ll hate yourself in the morning.

Next time can we just do it on the floor?

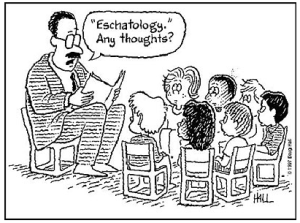

“Down, down, on to the eschatological bed. Pages chafed me; my blood wept onto them. My cheek nestled against the scratch of paper. My cock was barely a ghost, but I did not suffer panic.”

— The Quiddity of Wilf Self by Sam Mills.

We’re gonna need a bigger boat

“We got up from the chair and she led me to her elfin grot, getting amonst the pillows and cool sheets. We trawled each other’s bodies for every inch of history.” — Noughties by Ben Masters

If you wanna be a pony soldier you gotta act tough. Now mount up!

“Now his big generative jockey was inside her pelvic saddle, riding, riding, riding, and she was eagerly swallowing it swallowing it swallowing it with the saddle’s own lips and maw — all this without a word.” — Back to Blood, by Tom Wolfe.

Good thing she didn’t raise cacti

“He began thrusting wildly in the general direction of her chrysanthemum, but missing — his paunchy frame shuddering with the effort of remaining rigid and upside down.” — Rare Earth by Paul Mason.

Or maybe it was the Ben & Jerrys she dabbed behind her knees

“She smells of almonds, like a plump Bakewell pudding; and he is the spoon, the whipped cream, the helpless dollop of warm custard.” — The Yips by Nicola Barker.

I AM big, he said. It’s the pictures that got small

“This is when I take my picture, from deep inside the loving. The Canon is part of my body. I myself am the ultrasensitive film — capturing invisible reality, capturing heat.” — Infrared by Nancy Huston

Wouldn’t it be wubberly?

“And he came. Like a wubbering springboard. His ejaculate jumped the length of her arm. Eight diminishing gouts. The first too high for her to lick. Right on the shoulder.” — The Divine Comedy by Craig Raine

Mind the gap!

“In seconds the duke had lowered his trousers and boxers and positioned himself across a leather steamer trunk, emblazoned with the royal arms of Hohenzollern Castle. ‘Give me no quarter,’ he commanded. ‘Lay it on with all your might.’”– The Adventuress: The Irresistible Rise of Miss Cath Fox by Nicholas Coleridge

There. Now don’t you feel better?