by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

If you’ve been in my workshops or read a few of my writing books, you know about the “pet the dog” beat. The name is not original with me, but comes from the old Hollywood screenwriters. Blake Snyder changed it to “save the cat.” So pet lover-writers can choose their preferred metaphor.

I have refined the concept to make it something more specific than merely doing something nice for someone. In my view, the best pet-the-dog moments are those where the protagonist helps someone weaker or more vulnerable than himself, and by doing so places himself in further jeopardy. Thus, it falls naturally into Act 2, usually on either side of the midpoint.

I think of Katniss Everdeen helping little Rue in The Hunger Games. Or Richard Kimble in the movie The Fugitive, saving a little boy’s life in the hospital emergency ward (and having his cover blown as a result).

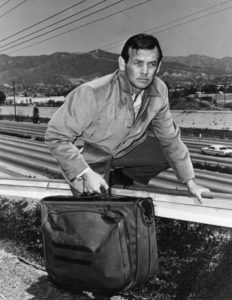

And speaking of The Fugitive, I’ve been watching the old TV series starring David Janssen. The show was a big hit in the 60s, and after watching a few I came to see that a big part of the reason is the pet-the-dog motif in almost every episode. There usually comes a time when someone is in need of medical attention. Kimble, therefore, has a dilemma. He can help and give away his medical skills (leading to suspicions about his background). Or he can quietly walk away.

What do you think this decent guy does?

An episode called “Fatso” will serve as an example. It’s a particularly good entry, directed by one of the best of that rare breed, the female Hollywood director—Ida Lupino.

Kimble (now using the name Bill Carter) has hitched a ride with a traveling salesman who is fighting off sleep. For safety’s sake, Kimble takes the wheel into the next town. Unfortunately, an errant driver forces Kimble to swerve and rear end a parked car.

Knowing the local cops will soon be on the scene, Kimble tries to sneak away, but is nabbed by the sheriff and arrested for fleeing the scene of an accident. They take his prints. Kimble, sitting in the clink, knows it’s just a matter of time before they identify who he is.

He shares his cell with a sad sack, an overweight drunk named David (played by that reliable character actor of the time, Jack Weston). When the sheriff comes to release David, Kimble socks the lawman and knocks him out. He heads for the door. David begs Kimble to take him along. They hop a train, heading for David’s boyhood home.

Meanwhile, Lt. Philip Gerard (Barry Morse), who is always one step behind Kimble, gets the report based on Kimble’s prints. He flies to Kentucky where all this is taking place.

Kimble learns that David, who everyone calls “slow,” wants to see his estranged father, who is dying on the horse ranch where he grew up. David is full of fear because of his father’s disapproval. Something happened in the past that caused his father to throw him out.

Kimble and David arrive at the ranch and are met by David’s younger brother, Frank. This guy is a real jerk. He calls David “Fatso” and needles him about that terrible thing that happened.

Frank is also suspicious of Kimble. Why would a guy like this befriend a loser like David?

As the episode goes on, with Gerard getting closer and Frank feeding the local sheriff his suspicions, Kimble tries to help David. Knowing that the only way David can become whole again is to confront the past, not run from it. To gain David’s trust, Kimble admits he’s a doctor. He then walks David through the night that the barn burned down and killed several horses. David was drunk and alone on the farm, and everyone, including David, is convinced he set the fire.

But Kimble does some digging and finds out that Frank was AWOL that night from the local army base. He presents this evidence to David’s father and mother. They confront Frank. He confesses. He set David up to get him disowned and out of the will.

David’s father asks for David’s forgiveness.

It’s all very redemptive, but there’s one problem: Gerard has just pulled up to the house with the sheriff!

The mother, played with gusto by that wonderful character actress Glenda Farrell, sends Kimble out the back door and proceeds to delay the investigators.

In each show’s epilogue, as we see Kimble disappear into the night, we hear the dulcet tones of one of the great voice-over actors, William Conrad, giving an ominous send-off. In “Fatso,” he says: “A Fugitive has to watch his step. Every step he takes, every hour, every minute, every second, any move he makes might lead to Death Row. There’s no way of knowing in advance. There’s never any way of knowing.”

Thus, virtually every episode is built around Kimble, on the run, arriving in some locale where he manages to pick up a menial job, but then gets involved with another character who is having some life-and-death problem, too … and Kimble is in a position to help.

I say this pet-the-dog motif is the secret of the show’s popularity. David Janssen was perfect for the part. He does a lot of acting with his face—trying to appear innocent as the questions get more pointed; attempting to ignore someone’s troubles even as his core goodness makes that impossible.

The movie works in the same way, with a similar stellar acting job by Harrison Ford. There’s one moment that makes me smile every time. After Kimble saves the little boy’s life in the hospital, he’s confronted by a doctor (Julianne Moore) who had seen him checking out the boy’s X-ray. She calls security. Kimble races to the stairs and starts down, almost bumping into someone.

“Excuse me,” he says.

I love it! Even as he’s running for his life, he can’t give up his fundamental decency.

Why do we respond so strongly to this motif? It’s not hard to understand. In this life, which Hobbes described as “nasty, brutish, and short,” we long for decency, thirst for kindness, are grateful for compassion. Seeing it manifested in a lead character draws us to him, creates the bond that is one of the big secrets of successful fiction.

What are some of your favorite pet-the-dog moments in movies or books? Don’t you find yourself really drawn to characters who show compassion for the vulnerable?