by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

My doctor is a sharp young guy. He seems impressed that I’m a writer of fiction  who manages to make a living that way. He once wistfully mentioned he would like one day to write a book.

who manages to make a living that way. He once wistfully mentioned he would like one day to write a book.

I told him he should do it. Then I asked him if one day I could take out a gallbladder. He said, “Probably not.”

I guess the barriers to entry into the medical profession are a bit higher than it is for would-be scribes. Too bad. Just once I’d like to say to a surgical assistant, “Scalpel … Sponge … Junior Mint.”

In any event, I go in yearly to get checked, even if I feel in the pink. I talk to the doc, get my blood drawn, then wait for the reports. Every now and then he makes a suggestion and I try to follow it, unless it involves red meat.

Your novel needs a checkup, too. I like to schedule mine at around the 20k word mark. I’m not so far in that I can’t do some remedial work if necessary. There are some tests I like to run. Let me commend them to you.

Blood Test

Is your story’s lifeblood healthy? Here’s how you can tell: Your Lead is facing an issue of life and death –– physical, professional, or psychological. That raises the stakes to the highest level. That keeps the blood flowing and the reader reading. Even if you’re writing a comic novel, the characters have to believe the central question is of the utmost importance.

Heart Rate

Are you connected emotionally to the story? I don’t mean you have to end up like Joan Wilder finishing her book at the start of Romancing the Stone (for more on that, see Rob’s post from last Wednesday and especially P. J.’s comment.)

What it does mean is that you must have some connection to the characters that makes you, the author, care about what happens to them. If you haven’t got that, find it before you move on. Feel something before you write anything.

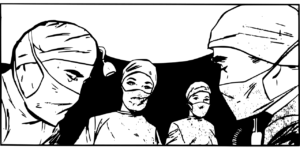

Character Endoscopy

Those little endoscopes (“viewing tubes”) enter your body via … through a … just take my word for it, in they go, to get a picture of what’s inside you.

You need something going on inside each main character, too, under the surface. We usually refer to this as motivation. Often that’s enough, but I like to know what’s behind it, what created it.

I don’t do extensive character biographies. Those never quite worked for me. But I do want to know a few key things, including a “wound” from a past trauma that haunts the character in the present (sometimes we call this “the ghost.”)

Joint Pain

Are your scenes working? They are the connections, the things that hold your story together. Having a dull scene is like having a knee go out on you. Everything stops. You can’t move forward.

Pain, the doc will tell you, is a good thing when it tells you Hey! You gotta take care of this, buddy!

And that’s what dull scenes are telling you.

Now, it’s true that you sometimes are too close to your story to know what’s dull. Often, it’s not until someone else looks at your manuscript that the pain is revealed to you.

I think it’s best if you know what to look for and fix it yourself, and soon.

First, do you have a feeling that a scene you wrote isn’t quite right? Go there and ask:

Do the characters in this scene have conflict, even if it’s subtle, with one another?

- Is there anything surprising in the scene? Unexpected?

- If the character is alone, is there some form of fear inside him? (From simple worry to outright terror?)

- Does the scene drag on too long?

Second, if the scene still doesn’t work treat it like a tumor and cut it out.

Hearing Check

How does your dialogue sound?

If the characters sound too much alike, no good. Each character deserves a distinct voice.

If your dialogue is always in complete sentences, you’re missing the power of compression.

If your dialogue attributions (said, asked) are being propped up by adverbs (he said haltingly; she asked imploringly) you’re diluting, not adding to the emotion of the scene.

(I will modestly hype my book, How to Write Dazzling Dialogue, because I believe dialogue is the fastest way to improve a manuscript.)

Eye Exam

Do your descriptions paint a vivid picture that pulls a reader into the story world? We are a visual culture, so you need to think and write cinematically. Like this:

The sun that brief December day shone weakly through the west-facing window of Garrett Kingsley’s office. It made a thin yellow oblong splash on his Persian carpet and gave up. (Robert B. Parker, Pale Kings and Princes)

Sol Stein counsels, “Have something visual on every page.” We’re weaving a dream, after all, and dreams are movies in the mind.

So what about you? Is your manuscript in pain? Where does it hurt? The medical staff of TKZ is here to help!