by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

The other night, Mrs. B and I re-watched the 1999 BBC adaptation of David Copperfield. Superb. And what a cast: young Daniel Radcliffe as David, the legendary Maggie Smith as Betsy Trotwood, Bob Hoskins as Micawber, Ian McKellen hilariously chewing the scenery as Mr. Creakle, and so on down the line.

The other night, Mrs. B and I re-watched the 1999 BBC adaptation of David Copperfield. Superb. And what a cast: young Daniel Radcliffe as David, the legendary Maggie Smith as Betsy Trotwood, Bob Hoskins as Micawber, Ian McKellen hilariously chewing the scenery as Mr. Creakle, and so on down the line.

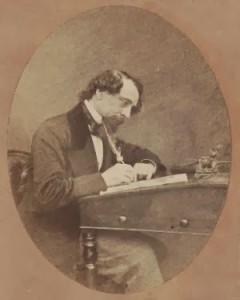

It made me wonder again at how Dickens, with quill and ink, turned out massive tomes, full of plot twists and unforgettable characters, like Peggotty, Steerforth, Mr. Dick, Barkis, Uriah Heep. Dickens never gives us colorless, throwaway story people.

So I went on a little journey to research Dickens’ method. I wanted to find out if he was an outline guy, a pants guy, or something in between. My conclusion is that he started a project with the “big picture” in mind, along with some main characters, but allowed himself room to expand and explore as he went along, with help from a trusted beta reader and his own wife.

We know Dickens wrote in serial form, sometimes in periodicals, sometimes in pamphlets. I read somewhere that anxious readers would often gather at the docks when the boats came in with the delivery of the latest installment.

I discovered a massive biography of Dickens by John Forster, the man who read almost everything Dickens wrote before it was published. In the clip below, Forster tells about the writing of Oliver Twist. (“Kate” was Dickens’ wife.)

Then, on a “Tuesday night,” at the opening of August, he wrote, “Hard at work still. Nancy is no more. I showed what I have done to Kate last night, who was in an unspeakable ‘state’ from which and my own impression I augur well. When I have sent Sikes to the devil, I must have yours.”

“No, no,” he wrote, in the following month: “don’t, don’t let us ride till to-morrow, not having yet disposed of Fagin, who is such an out-and-outer that I don’t know what to make of him.” No small difficulty to an inventor, where the creatures of his invention are found to be as real as himself.

The ending of The Old Curiosity Shop was suggested by Forster:

He [Dickens] had not thought of killing her [Little Nell], when, about half-way through, I asked him to consider whether it did not necessarily belong even to his own conception, after taking so mere a child through such a tragedy of sorrow, to lift her also out of the commonplace of ordinary happy endings so that the gentle pure little figure and form should never change to the fancy. All that I meant he seized at once, and never turned aside from it again.

This sums up the Dickens “method”:

Its [The Old Curiosity Shop] effect as a mere piece of art, too, considering the circumstances in which I have shown it to be written, I think very noteworthy. It began with a plan for but a short half-dozen chapters; it grew into a full-proportioned story under the warmth of the feeling it had inspired its writer with; its very incidents created a necessity at first not seen; and it was carried to a close only contemplated after a full half of it had been written.

I draw a few lessons from Mr. Dickens.

1. Plan your novel, but give it room to breathe. Dickens didn’t sit down with no idea of where he was going. He started with a main character in mind, a set of problems for that character, some secondary characters, and an envisioned outcome. But for each section he wrote he was flexible in how things developed. He could change his plan or his characters if he so desired. I can’t prove this, but I have a feeling James Steerforth in David Copperfield was such a character. Initially a hero to David, he became the driver of the tragic Little Emily subplot.

2. Unforgettable fiction is written when you are imbued with “warmth and feeling.” Note: You can’t get that from a machine. You get candy bars and soft drinks from a machine, not living, breathing, blood-pounding, heart-racing fiction, the only kind that turns browsers into readers, and readers into fans.

3. You produce warmth and feeling by experiencing the lives of your characters. The great alchemy of unforgettable fiction is moving your characters from your head to your heart. The great Dwight Swain wrote: “People read fiction for feeling. Whether they know it or not, they grope for stimuli that move them. The thing in fiction that gives them this stimulation is emotion projected through characters.”

You’ve got to feel the emotion before you can project it. An added benefit, Swain says, is that this how you produce “zest”—the “best way to escape the fatigue and boredom that endless hours of writing often bring.”

Recall what Forster said, that “the creatures of his invention are found to be as real as himself.” In the 1850 preface to David Copperfield, Dickens wrote:

I do not find it easy to get sufficiently far away from this Book, in the first sensations of having finished it, to refer to it with the composure which this formal heading would seem to require. My interest in it, is so recent and strong; and my mind is so divided between pleasure and regret—pleasure in the achievement of a long design, regret in the separation from many companions—that I am in danger of wearying the reader whom I love, with personal confidences, and private emotions.

4. Get the benefit of another set of eyes. A great editor or beta reader is gold. You’re too close to your manuscript to spot subtle—or sometimes obvious—errors. You may be blind to an obvious plot hole or undeveloped character motivation. If you don’t deal with them now, readers and reviewers will deal with them later.

5. Be developing your next project. Dickens had a family to support and debts to be paid. He always had a next project in mind. He kept a notebook of ideas. Forster: “In it were put down any hints or suggestions that occurred to him. A mere piece of imagery or fancy, it might be at one time; at another the outline of a subject or a character; then a bit of description or dialogue; no order or sequence being observed in any. Titles for stories were set down too, and groups of names for the actors in them.”

And that’s not humbug. Comments welcome.