By John Gilstrap

Just to set the stage, I consider these Killzone posts to be a corner of the social media universe. It’s different than Facebook and X in that the topics are more focused, but it’s still an opportunity to address people with whom I would otherwise not normally interact. In the social media universe I am the John Gilstrap I choose to project, which is often a shade different than the John Gilstrap that actually is.

For example, I am always healthy and happy on social media. By any reasonable assessment, I live a blessed life, both professionally and personally. As a player in the entertainment business (which is what this writing gig really is), my job is to entertain–to be interesting, insightful, maybe even amusing from time to time. The last thing people want to hear from me are everyday life problems. Folks have plenty of those in their own lives.

Sometimes, though, a personal problem is worth sharing. So, here we go . . .

My back has been a mess for decades–some of it due to overzealous firefighting in my youth, some due to heredity, and some due (dammit) to the fact of getting older. Back in 2019, I had three levels of my cervical spine fused to take care of lightning bolts shooting down my arms. That procedure was very successful, but my lumbar spine continued to trouble me.

If you’ve had sciatica, then you know the torment of the nerve pain in your legs, and of that invisible ice pick in your buttocks. For years, the pain would arrive for a week or two and then go on hiatus for months. For the last six months or so, the pain took up residence and partied daily. It got to the point where I couldn’t walk more than 20 steps without having to stop and try to recover.

My MRI showed nothing but bad and worse news. Worst of all was severe stenosis at L4 and L5. In essence, this meant that bits of bad discs, bone spurs and fluid were directly impinging on the nerves of my lower back.

Time to see the neurosurgeon.

On June 4 (last week), the neurosurgical team at the Berkeley Medical Center successfully performed a two-level laminectomy and microdiscectomy on my lumbar spine. The minimally invasive procedure took about two hours. The medical miracle workers removed a part of my backbone to gain access to the nerve roots, and from there Roto-Rootered all that crap away and removed the pressure that was causing all the pain. The instant I awoke, I knew that the procedure had done its job. All the nerve pain was gone.

There remained, however, the fact that they’d stuck a knife in my back and pulled all those muscles aside to gain access to what they needed to do. The muscles respond with a tantrum of spasms because that’s just what they do. Plus, there’s the discomfort caused by cut-away bone and the steel surgical staples they used to close the wound. A lesser man would call that pain. I just dropped a lot of F-bombs.

(As an aside, note that the autonomic nervous system–your fight-or-flight instincts–don’t recognize the difference between a friendly surgical wound and a tiger attack. It reacts with a pulse of adrenaline and healing chemistry and energy. Now you know why you’re so tired after even a minor medical procedure.)

They sent me home with pills–Oxycodone every 6 hours for the pain and Tizanidine three times a day for the muscle spasms. I was to be a junky for three days. Cool beans.

Except . . . Among the side effects of Tizanidine, listed right there on the bottle, “Might cause hallucinations.”

Which brings us to the real meat of this post. Boy howdy, did I hallucinate! Only at night, and maybe when I was asleep, but if they were dreams, they were some wild, vivid dreams. Three dimensional dreams, if that even makes sense. On the morning after my surgery, when I woke up in bed, I asked my wife if she was real, because the first time I’d done that she’d not been. Whoa.

At Surgery Plus Two, the hallucinations took a turn that give me a chill even as I write this today. I was lying on my back and the bed had become some kind of floating vessel, moving down a river as I looked up to a starry sky through the silhouettes of leafy trees. It was very peaceful, very comforting. Extremely vivid. Then came the faces of relatives who have passed. They floated by one or two at a time, all of them smiling. These were not family photograph images. Uncles, aunts, cousins. I didn’t even recognize some of the faces, but they projected an embracing warmth that I don’t know how to describe. My dad’s was the only face in full color, dressed in his Navy uniform.

I panicked enough to awaken and say a prayer for me and for my family–concerned that this was somehow my version of the “bright light” that people report from near-death experiences. I wasn’t ready to go.

Immediately, sleep returned (or did it?) and instead of seeing the sky and my relatives, I was looking down on myself in a boat as I was cut free from a mooring and allowed to float away.

I awoke again with a feeling of great peace, then sleep returned.

In the morning, I sobbed as I relayed the story to my wife. To be honest, I’m not doing all that great as I write it now.

I don’t know what to make of this. A vivid imagination is an occupational hazard, so I have to acknowledge that the whole river sequence was merely the creativity factory working in overdrive. But I think I choose otherwise. I think there are many aspects of life and living that we just don’t understand, and I choose to believe that love transcends everything we think we know.

I don’t think my family had gathered to tell me it was my time, but rather to tell me that they were at rest and that when my time comes–may it be many, many years from now–I’m going to be embraced when I arrive.

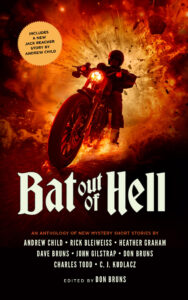

“All Revved . . .” is, hands down, the darkest story I’ve ever written. You can find it in the recently published anthology, Bat Out Of Hell, edited by Don Bruns, and the story is inspired by the title of one of the songs on the famous Meat Loaf album from the 1970s. The story tells the tale of Ace Spade, an off-duty firefighter and search and rescue operator who’s trying to impress a young lady with his four-wheeling skills in the back woods of West Virginia when things go terribly wrong. After he wrecks his Jeep in the middle of nowhere, the man who they think is there to lend assistance turns out to be a killer who wants to hunt them down and kill them.

“All Revved . . .” is, hands down, the darkest story I’ve ever written. You can find it in the recently published anthology, Bat Out Of Hell, edited by Don Bruns, and the story is inspired by the title of one of the songs on the famous Meat Loaf album from the 1970s. The story tells the tale of Ace Spade, an off-duty firefighter and search and rescue operator who’s trying to impress a young lady with his four-wheeling skills in the back woods of West Virginia when things go terribly wrong. After he wrecks his Jeep in the middle of nowhere, the man who they think is there to lend assistance turns out to be a killer who wants to hunt them down and kill them.

But with the upcoming release of Burned Bridges, the first entry in my new Irene Rivers thriller series (launched yesterday!), I finally have an answer.

But with the upcoming release of Burned Bridges, the first entry in my new Irene Rivers thriller series (launched yesterday!), I finally have an answer. One late autumn afternoon, as I was walking around our property in West Virginia in the company of Kimber, my 22-pound protector and watchdog, I was squeezing my brain to hatch an idea that felt right. I wanted it to be West Virginia-centric, but in the way that C.J. Box’s works are Wyoming-centric.

One late autumn afternoon, as I was walking around our property in West Virginia in the company of Kimber, my 22-pound protector and watchdog, I was squeezing my brain to hatch an idea that felt right. I wanted it to be West Virginia-centric, but in the way that C.J. Box’s works are Wyoming-centric.

Everything changed when that jerk was foolish enough to kill John Wick’s dog, Daisy, and the world was introduced to an established, effective, but until that movie, a little known set of gun handling techniques called Center Axis Relock.

Everything changed when that jerk was foolish enough to kill John Wick’s dog, Daisy, and the world was introduced to an established, effective, but until that movie, a little known set of gun handling techniques called Center Axis Relock. This technique embraces the fact that gunfights are often intimate affairs, conducted within bad breath distance. From the instant the pistol is drawn, it’s ready to join the fight. At the draw, your body is severely bladed toward the target, such that your elbow is pointing at the bad guy’s center of mass. In close quarters, your elbow acts as a front sight and allows you to get shots on close-in targets instantly.

This technique embraces the fact that gunfights are often intimate affairs, conducted within bad breath distance. From the instant the pistol is drawn, it’s ready to join the fight. At the draw, your body is severely bladed toward the target, such that your elbow is pointing at the bad guy’s center of mass. In close quarters, your elbow acts as a front sight and allows you to get shots on close-in targets instantly.