@jamesscottbell

When I began studying writing in earnest it was with an eye to becoming a screenwriter. This was back in the day of the “screenwriting guru” explosion. Syd Field was the granddaddy. His Screenplay was my foundational book and led to my eventual breakthrough on structure. Soon, Robert McKee came on the scene, then John Truby and a few others. Acolytes of each would claim that their guy was the true originator of screenwriting knowledge for the unwashed mass of wannabes.

Only none of them were. The original guru was a veteran Hollywood screen and TV writer who started teaching for UCLA Extension in the 1950s. His book, Writing the Script, came out in 1980. Wells Root was his name and you can look up his credits on IMDB.

Wells Root directing Donna Reed in Mokey (1942)

The other day I turned on TCM and decided to watch a little of the upcoming flick, a B gangster picture from the 30s called Public Hero #1. I saw that it had Chester Morris in it, and I like his work. The credits rolled and lo and behold Wells Root was the screenwriter. Now I watched with added interest, and ended up taking in the whole thing. The plot moved, had twists and turns and original characters. A crisp 89 minutes. Nicely done, Wells!

So I went to my bookshelf and pulled down Writing the Script for a re-read.

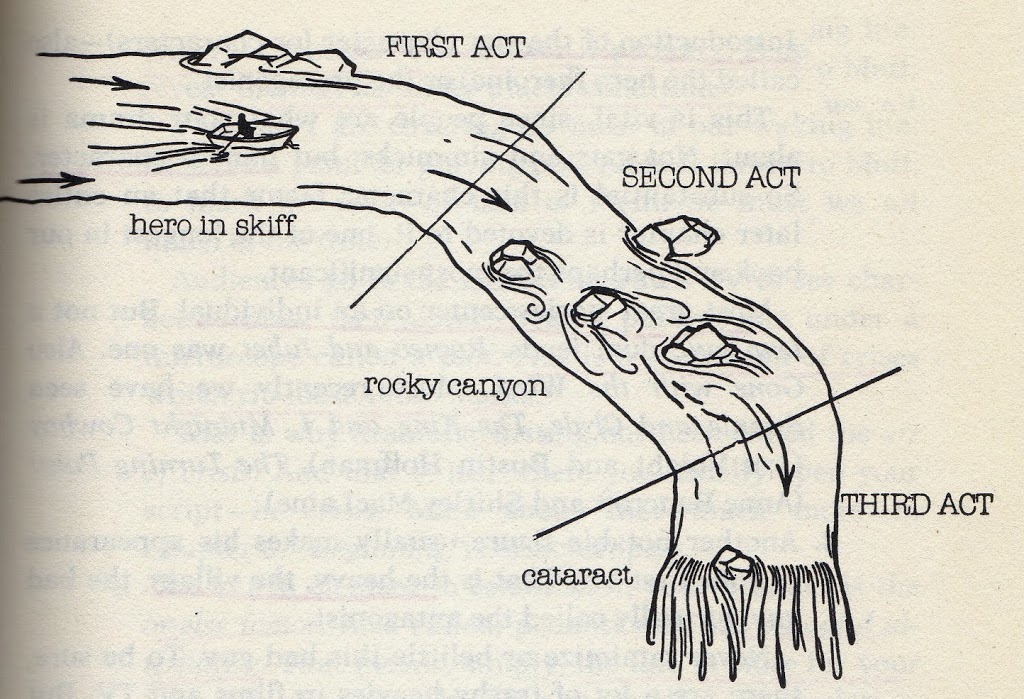

It’s nice to make its acquaintance again. Writing the Script is filled with gems of wisdom for both fiction and screen writers. And Root’s illustration of the three-act structure (as a raging river) is brilliant. He came up with this metaphor years before Syd Field’s famous three-act “paradigm.”

You see how the hero is in the river of story, being pulled by the current despite his best efforts with the oars. He gets thrust into the hazardous, rock-infested white water of Act 2. He fights all that only to hit a waterfall in Act 3. As he goes over the audience is asking, Will he drown or somehow make it to safe water?

I’ve always thought the best writing education would have been to be a young writer in Hollywood in the 30s. Then you could have hung out at Musso & Frank, listening to old scribes like Ben Hecht and Wells Root and John Howard Lawson. Over Martinis they would have provided a graduate course in the finer points of dramatic writing.

Since that era is long gone, Root’s book will have to do. So pull up a chair and listen to some of his advice:

Ultramodern, unstructured story design has an erratic record bringing bodies to the barn.

Drama favors the great saint or the great sinner—heroes and rascals who are above the common run. But they must still be as welcome in the village pub as in the manor house.

If you have the guts to be totally honest, nobody can write a character exactly as you can.

An unmistakable mark of a master craftsman is that he individualizes all his characters. (In the margin of the book I had scribbled “Moonstruck.”)

Although your heavy is a horror, make him or her also a vulnerable human being.

Write a man or woman or child who is everybody, but who becomes in your dramatic story an absorbing variation, a striking original.

The heights of emotional drama dwell in these scenes that plead truth from opposed points of view. Such conflicts, you will find, play with a special luminous power.

A story maker’s urgent priority should be awareness. A writer is always in his working clothes.

Agents and producers are flooded with the commonplace. Routine work will get you nothing but routine indifference.

So there it is, an afternoon hanging out with Wells Root, the first of the great screenwriting gurus.

Is there a “wise old scribe” in your background? Somebody from whom you got much needed advice? Tell us about it. [NOTE: I’ll be in travel mode today, so talk amongst yourselves and I’ll try to catch up later]

Ever since I discovered people wrote books, not magical book faeries, I wanted to be a writer. I would write shorties on the yellow paper with wide lines they gave us to practice our handwriting. I read every book in our school library.

By the time I was in high school, I was writing novel length things, but still uncertain as to how to write a novel. I kept getting caught up at the end. Events just dragged on and on.

This was before the Internet was as common place as it is now. Chat rooms and blogs and stuff existed but I wasn’t aware of them. I felt lost, like I had no where to turn (I didn’t know there were books on writing out there).

Then Stephan King wrote “On Writing” and I devoured it in one sitting. Here he was, explaining writing in plain terms so other people could understand. I still remember sitting on my bed having an epiphany. So this is how they did it. From there I checked out other books on writing, and found blogs, and it’s been a great journey since.

Jim, So glad you shared this. Your background in screen writing has served you well. I’ll be ordering that book. Meanwhile, the diagram of the hero on the river is a wonderful illustration of the three-act structure, and I’ll certainly steal it for a course I’m teaching later this spring–with proper attribution, of course. Travel safely.

The most prolific old scribe in my background was Isaac Asimov. I never met him, but he definitely influenced me…about what I wanted to do as a writer as well as what I didn’t want to do. The old scribe that was an indirect but direct personal influence (he’d never remember me, but he was my prof at UCSB) was N. Scott Momaday, a Pulitzer-Prize winning author. He had a way with words I wanted to emulate even though I knew I’d never write “literary fiction.”

Other than these two, there are many more authors who’ve inspired my writing, including someone named James Scott Bell 😉 (I’m not making this up…I don’t often get the chance to say that in my comments to blog posts on the internet.) I don’t necessarily agree with them or love what they write, but I’ve learned from them, and that counts for a lot.

r/Steve

I agree on Steve’s JSB comment. He’s how I found TKZ.

I’ve recently rediscovered an influence from the past: Looney Tunes! I’ve started watching them with my daughter. As I watched the first few I realized how distinct each character is. None of the characters is fluff. They all have a specific purpose in each story and they all have very distinct personalities. Even without the vastly different bodies, no one would mistake Elmer Fudd for Bugs or Daffy. Their dialogue and characteristics are so different. Maybe all those hours in front of the tube as a kid weren’t a waste! I just need to tap into it.

I will second Elizabeth on King’s “On Writing.” There is a passage in there (paraphrased,) “You don’t need anyone’s permission to write. But if you do, okay, you have my permission.”

That an the short story challenge in the book. It was long since over by the time I got my copy, but I took it to heart and wrote the short and published it on a writers’ group bulletin board. That got me started.

Another “wise old scribe” is the lecture series on screenwriting on the new from Stephen J. Cannell. From the great beyond his essay succinctly taught me the 3-act story arc and I send many many people there hoping they will have the same epiphany.

And, in my acceptance remarks for my award, I thanked John Gilstrap for his immortal words, “this sucks.” Also a shout-out to TKZ.

Terri

Had a cranky old boss (I think I’ve mentioned him) who once told me, “The readers don’t care what you think. They don’t care about you. They care about the story. Stop getting in its way.”

Ray Bradbury spoke at my high school back in the ’70s, and he was great and inspirational, but didn’t say anything half as useful as that “advice” from my boss.

I vote for Stephen J. Cannell. Televsion changed forever when he introduced the multi-hero.

JSB –

Sister St. Edmund, my teacher in 8th grade. She had an unfortunate proclivity for dishing out corporeal punishment but also communicated a love of reading and taught me not to fear writing.

Mary Carroll Moore provided great instruction in a series of seminars at the Loft Literary Center that were a great foundation for further learning.

Jodie Renner as my committed editor has shown me a tremendous amount about making a story better! Truly fortunate to have found her (through this blog!) more than a year ago.

And – all ass-kissing aside – Sir JSB. Through years of your TKZ posts and participation in the 4 day “Story Masters” conference, I’ve learned a tremendous amount.

Perhaps singular is your example of love of story and commitment to craft. Without pretense or ego-stroking you really give your all to educate. I very much appreciate the gift of your knowledge and experience. (and the other TKZ folks including John Ramsey Miller and John Gilstrap) – Thanks!

Thanks for all the great comments, folks. It’s nice to know that authors can “pay it forward” as it were and truly help others along.

I’m such a visual person. The raging river picture speaks volumes to me. Thanks…hoping to share it with my writers group.

Instruction guides for writers can be very helpful. I own and have read–and reread–James Scott Bell’s Plot and Structure. But I still get the most help from reading certain novels and plays. Not all, just certain ones. For instance, in today’s post, JSB quotes the following from Wells Root: “An unmistakable mark of a master craftsman is that he individualizes ALL his characters.” This principle is one I work hard follow–but I didn’t learn it from Wells Root. I learned it from Shakespeare. Look at his plays, and what you find is characters, from least to most important, all of which stand out as individuals, not as clichés. It’s hard to do this without slowing down the narrative, but it’s what I try to do in my novels.