by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

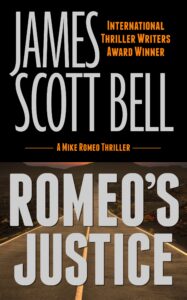

Today’s post is brought to you by the new Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Justice, now available for pre-order at the ridiculously low deal price of just $1.99. (Outside the U.S., go to your Kindle store and search for: B0CHMTRC6N)

Today’s post is brought to you by the new Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Justice, now available for pre-order at the ridiculously low deal price of just $1.99. (Outside the U.S., go to your Kindle store and search for: B0CHMTRC6N)

Which brings me to the subject of minor characters (you’ll find out why in a moment).

First, let’s define terms. Though you’ll find variations on how fictional character types are defined, I’ll break it down this way: Main, Secondary, and Minor.

Main characters are those who are essential to the plot and usually appear in several scenes.

Secondary characters are supporting players who have a more limited, though sometimes crucial, role.

Minor characters are those who are necessary for a scene or two, and may only appear once, twice or a few times throughout.

For example, in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, the main characters are Sam Spade, Brigid O’Shaughnessy, Joel Cairo, and Casper Gutman. They recur throughout the book.

Effie Perrine, Sam Spade’s secretary, is a secondary character, who provides information and plot relief later in the story.

Wilmer Cook, Gutman’s enforcer, is a minor character, as is Tom Polhaus, Spade’s cop friend.

I call secondary and minor characters “spice.” They can add just the right touch of tasty flavor to a story. But if they’re bland or stereotypical, you’re wasting the ingredient.

So where do you start? By giving each one a tag (something physical) and a singular way of talking.

The Maltese Falcon is a masterclass in characterization. The following descriptions are for main characters, but I include them as examples of Hammett’s orchestration—making each character different in order to increase conflict.

Early on, Sam Spade gets a visit at his office from an odd little fellow named Joel Cairo.

Mr. Joel Cairo was a small-boned dark man of medium height. His hair was black and smooth and very glossy. His features were Levantine. A square-cut ruby, its sides paralleled by four baguette diamonds, gleamed against the deep green of his cravat. His black coat, cut tight to narrow shoulders, flared a little over slightly plump hips.

Cairo has a distinct way of speaking:

“May a stranger offer condolences for your partner’s unfortunate death?”

***

“Our conversations in private have not been such that I am anxious to continue them.”

Then we have the “fat man,” Casper Gutman, who—

was flabbily fat with bulbous pink cheeks and lips and chins and neck, with a great soft egg of a belly that was all his torso, and pendant cones for arms and legs. As he advanced to meet Spade all his bulbs rose and shook and fell separately with each step, in the manner of clustered soap-bubbles not yet released from the pipe through which they had been blown.

When he talks to Spade, he sounds like this:

“Now, sir, we’ll talk if you like. And I’ll tell you right out that I’m a man who likes talking to a man that likes to talk.”

***

“You’re the man for me, sir, a man cut along my own lines. No beating about the bush, but right to the point. ‘Will we talk about the black bird?’ We will. I like that, sir. I like that way of doing business. Let us talk about the black bird by all means…”

You get the idea. Physicality and speech pattern. Tags and dialogue. Even for minor characters. In Falcon, Wilmer Cook, the “gunsel,” plays a small but important role. Hammett describes him only as a “youth” wearing a “cap.” When he talks, he tries too hard to sound like a tough guy.

Dwight Frye as Wilmer Cook in the 1931 version of The Maltese Falcon

The boy raised his eyes to Spade’s mouth and spoke in the strained voice of one in physical pain: “Keep on riding me and you’re going to be picking iron out of your navel.”

Spade chuckled. “The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter,” he said cheerfully. “Well, let’s go.”

And while we’re on the subject of minor characters, I want to talk about how they can save your bacon when you close in on the end of your book. This happened to me as I was finishing the aforementioned Romeo’s Justice. My plot was rolling along nicely, unfurling several threads of mystery and suspense, strategically woven into the plot according to my outline. But when I got to the end, there was one thread that was still dangling. I needed to clear this up for the reader. But how?

I made up a minor character to explain it.

But wait, didn’t I just say this was at the end? You can’t just bring in some character at the very end, out of the blue, to save your keister, can you?

Of course you can! All you have to do is work that character into an early scene or two, setting him up for the big reveal.

I thumbed through my hard copy of the first draft and located a place in Act I where I could intro the character. I ended up with a minor character who I’m sure is going to show up in a future book.

This is what’s fun about being an author. You create your world and your people, and you remain sovereign over the proceedings. You can go back and move things around as you see fit. And then you can put the book up for pre-order.

What’s your approach to creating minor characters?

For me, writing as I do from deep third pov, a minor character is a chance to write a person with a whole life, seen briefly through the pov character’s eyes, and to pick something special about them.

Here’s one of the main characters, Andrew, saying goodbye after the wrap to one of the crew, in the Czech Republic:

“Photo? For friends?” The young Makeup man who had intimate knowledge of his facial flaws was suddenly shy.

He laughed, and snagged a passing crew member to take a few shots, some serious, others with himself making faces Dodgson likely never wore. He signed a still photo the lad produced diffidently, one of the location shots from the first days, ‘To Teodor—Thanks, Andrew,’ which got him a handshake. He pulled the boy into a rough bear hug to a startled grateful look, made sure it was recorded by motioning to their impromptu photog.

I will remember Teodor.

whole life, seen briefly

I like the way you put that, Alicia.

Interesting the timing on your posting about minor characters. I’m working on revisions to a story and in order to solve a particular story issue had gone in to insert a prologue featuring a minor character that will be crucial to tying things up in the end. But now I’m debating whether to keep the scene (not because it’s a prologue, though I know many advocate not to use them) but because I’m uncertain if the fact that it is a minor character in the grand scheme of things, will cause reader confusion, expecting that character to appear more central in the story than they ultimately will. Will have to think it over & see if there’s another way to solve my problem.

While Hammett’s examples read to me as overkill description, I am also aware that one of the things I have to routinely do when editing is beef up my character description as I tend to be too sparse in human description.

Looking forward to reading Romeo’s Justice when it drops in a few weeks!

Thanks, BK. One little rule of thumb is that the more descriptive time you give to a character, the more the reader expects to see that character. That’s why Hammett only describes Wilmer as wearing a cap. Whereas with Cairo and Gutman, we know they’re going to be around a lot.

I’ve got recurring minor characters throughout my Mapleton series, as most of the books take place in the same setting. Neighbors, witnesses, friends, peripheral staffers at the police station. Good timing on this post, as I was wondering why Rose and Sam haven’t shown up in this book, and maybe I need to go back and give them a moment or two of page time.

Always glad to hear I can help out some poor, forgotten minor character. Ha!

Whoa, I never thought about working a minor character into the story to tie up a plot thread at the end. Clever.

Thanks. Vera. I give a hat tip to my former colleague at Writer’s Digest, Nancy Kress, and her wonderful book, Dynamic Characters.

In my fantasy series, my minor characters are often unusual beings that are part of a fantasy world. Their description, their way of speaking, and how they move, is part of the larger description of the world in which they are found. And the stranger the better.

Occasionally, the minor character will become part of the plot for a several scenes, for example when a “Pink,” Pee Bee, pulls at the heartstrings of the MC, then begs to go along for the rest of the mission.

Congratulations on Romeo #8. I look forward to reading it.

Fantasy is such a great genre for peopling in minor characters. Sounds good, Steve.

New age cult in a small town of secrets. I can’t tell you how much I love that element. This will be an auto buy for me… in print (yes, indies, print is worth it. Some of us still wanna smell those sweet pulp pages).

Thanks, Philip. Print version will be coming!

I stayed up way too late last night reading Romeo’s Justice, essentially killing the sleeping pill I took. I’m loving it but now I’m trying to figure out which character you added—there are several worthy to be included in a future book.

Since I don’t always know who did it I often have to go back and beef up the actual antagonist’s story.

Wow, thanks Patricia. Easter egg time. 😁

I aim to have minor characters be distinctive, like an apartment manager in A Shush Before Dying working Sunday morning, wearing half-moon reading glasses on a silver chain doing a crossword puzzle, her manner pleasant but in charge, who is in just that one scene, but who makes a difference in Meg’s investigation.

Incidentally, The Maltese Falcon is the library’s “Murder of the Month” mystery book club read in the sequel, Book Drop Dead.

I’ve pre-ordered the latest Romeo novel. Congratulations on its impending release.

Thanks for the good word, Dale, and also for putting The Maltese Falcon in a book. Really need to get that in front of high school readers!

Minor characters are the “spice”. I like that!

In my novel, The Master’s Inn, there are a few. My favorite is a small boy who provides comic relief in tension-filled scenes. He’s a scamp with a wicked sense of humor wrapped in complete innocence. And he reminds me so much of one of my grandsons, who is a one-liner king.

Happy Sunday!

Deb, comic relief is one of the great uses of minor characters in thrillers. Nicely done.

Thanks, Jim!

And, BTW, nicely done to you, too. That minor character in Romeo’s Justice tied it up tidily for me… 🙂

Jim, minor characters as “spice” is a great definition. As a reader, I sometimes find them more interesting than the main characters and look forward to their reappearance.

Minor characters are almost always key components in my books. They are often related to the antagonist as henchmen or confidantes. Sometimes they have their own POV scenes in which they show their impressions of a main character from a perspective the reader hasn’t seen before. Often they are people who are overlooked or ignored by other characters in the story world, seen but not heard, treated like a piece of furniture. They always play pivotal roles in the plot, even if they only have a few scenes.

Did Hammett envision Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet when he wrote <Maltese Falcon or did director John Huston do masterful casting?

Hammett had no idea, as the book came out before anybody knew who Bogart, Lorre, or Greenstreet were. Now it’s virtually impossible to imagine The Story without them. Also, we have to include the magnificent Mary Astor in this group. That was the year she won the Oscar for best supporting actress for another film. She should have received another one for this!

Good news! A new Romeo book. I just pre-ordered Romeo’s Justice, and I’m looking forward to spending another evening or two with Mike, Ira, and friends.

“This is what’s fun about being an author. You create your world and your people, and you remain sovereign over the proceedings.” So true. And writing a series gives the author the opportunity to introduce a minor character in one book who may take on a larger role in others. For example, Mrs. Toussaint was a minor character in the third book of the Watch series, but she’s a major secondary character in my upcoming middle grade book, The Other Side of Sunshine.

Sound great, Kay. I’m reminded of the fun Janet Evanovich had with her Stephanie Plum minor characters.

I just did something similar, Jim. Three minor characters from a previous book came in handy in my latest. Not only was it a fun reunion for my MCs, but they played a vital role at the end. Love when that happens. 😀

“Came in handy.” Exactly!

Well, it’s not often the first line of a blog post sends me away screaming…in this case to Amz to make my pre-order, and screaming “I want it NOW!”

Aw, thanks for the scream, Justine. 😎

😂😂😂

I like the idea of having a minor character acting as the ‘holy spirit’ as it were, guiding my MC to the correct path.