“No passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone else’s draft.” ~H.G. Wells

By PJ Parrish

For most of my adult life, I made my livelihood in the newspaper business. My dream was to work for the Detroit Free Press, but I had to start out instead at a small suburban weekly called The Eccentric. It was a gift in disguise.

I did everything from taking and processing my own photos, to writing obits, to covering city council meetings where the surest thing to get the blood moving was a hot debate about sewers. The pinnacle of my career was being named editor of the Women’s Life section, Yeah, I’m that old and that’s what it was called in those days. I got to supervise a small staff of eager beaver stringers.

That was my first experience with learning how to tell others that their writing well, might need some work.

I was not very good at it. It took me a long time to learn that doling out criticism is a learned skill. All writers need honesty but it has to come with a healthy side order of kindness.

We talk a lot here at The Kill Zone about how to take criticism. Or its uglier sibling rejection. As writers, we deal with this at every level of our writing lives. Better grow a rhino hide or you’ll never make it, the conventional wisdom goes. But maybe we need to take a moment and talk about how to give criticism.

If you work with a critique group or if you are someone’s beta reader, then you definitely need to learn the fine art of diplomacy. We here at the Kill Zone deal with this all the time as we critique your First Page submissions. And I think I can speak for all of us that it’s often not easy to do this because there is a fine line between being helpful to a new writer and being discouraging.

Whenever I get a First Page submission, I go through a distinct process:

- First, I read the whole 400 or so words quickly, without any eye toward editing. I try very hard to read it as only a reader would who has just bought the book. Does the opening, at the minimum, pique my interest?

- Second, I ask myself: Do I have any prejudices against this TYPE of book that would make me unduly negative or even ignorant? For instance, I’m not a big sci-fi fan, and I recognize that I’m a little clueless about what works in YA these days. So I read such submissions with that caveat.

- Next, I ask myself if the submission has something to teach all our readers. It’s not enough, I think, for me to just red-ink grammar mistakes or such. I look for a larger issue in each submission that can help all our writers learn.

- Sometimes, you get a submission that just isn’t up to snuff enough to critique. The writer hasn’t yet gotten the very basics of the craft down. It’s pointless to teach English until someone knows their ABCs.

- I don’t like doing a submission unless I have something good to say about it.

And that last one is important. Because I remember how hard it was to get feedback when I was trying to publish my first mystery back in the late 1990s. Even though I had had four romances published by a big house, I didn’t really know how to write a mystery and my first two attempts were awful. Luckily, I had an agent who was a hard-nosed New York ex-editor. She frankly scared the hell out of me but she knew how to give honest criticism. She told me I was a very good writer but I didn’t understand the distinct structure of a mystery. She told me to go home and read. “Start with P.D. James and work your way up to Michael Connelly,” she said. So I did.

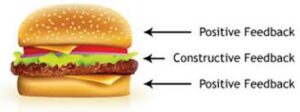

Once my mystery career took off, I then had to learn to take criticism from editors. I would turn in my manuscript and wait with a strange combination of eagerness and dread. Eagerness because I was sure I was going to get heaps of praise. (“This is great! We’re pushing it up to our lead title with a 100,000 first press run!”) Dread because I was sure I was a fraud. (“Listen, this isn’t quite what we talked about when you turned in your outline…”) The reality fell somewhere in between. I have been blessed to have some really great editors in my three decades of writing crime fiction. Each one of them understood what some have called the Hamburger Model of Criticism:

Start out by staying something nice about the manuscript.

Insert a big juicy slab of criticism.

End with saying something encouraging.

I think every editor I have ever worked with did this. And it always made the meat patty go down a lot easier. But here’s the the thing about the meat patty: It has to be constructive. Late in my journalism career, I was the Features Editor at a large Florida daily. I had an editor in chief who every morning took a red grease pencil to mark up every section of the paper. The comments were almost uniformly negative, of the type of “I don’t like this.” One day, in frustration, I asked him WHY he didn’t like something. He said he didn’t know. He was like judge who says “I can’t tell you what’s porn but I just know it when I see it.” Luckily, he was canned before I could quit.

A few other things I’ve learned about giving criticism:

- Resist the urge to fix the problem. Unless you really have the solution, it’s not a good idea to offer up the answer to another writer’s problem. You don’t know their book; you’re not inside their head. You might be able to tell them they have wandered off the trail and that you, as the reader, feel lost. But it is not up to you to show them which is the RIGHT trail to the end. They have to find their way.

- Watch your tone. Being snarky is, unfortunately, encouraged in our culture today. (I was curious about where the word “snarky” came from so I looked it up. It was coined by the Star Trek actor Richard William Wheaton in a speech he gave before a bunch of online gamers.) If you are asked for input, don’t be mean. Kindness is in short supply today and writers are like turtles without shells — easy to crush.

- Don’t take out your frustrations on someone else. Hey, you’re having a bad day. Your own book is falling apart. Your plot has more holes than a cheese grater. Your Dell died and your geek can’t do a data retrieval. Don’t vent your anger on someone else’s baby.

- Don’t boost your own ego. Some people like to show how powerful or intelligent or knowledgeable they are, and use criticism as a way of doing that. They are puffing themselves up, challenging others, going all Alpha dog. Nobody likes a bully.

- Let the person react. Giving a person a chance to explain why they wrote something the way they did helps their ego a bit and often, as they explain, they see where they can improve. It also makes you look fair.

- Be empathetic. You’ve probably had the same problems the other guy is having. So tell him. Be vulnerable and relate how it was hard for you to understand motivation or the three-act structure. Walk in their shoes.

- Don’t focus on the person. One of the hardest things beginning writers have to learn is to not take criticism personally. A rejection letter is never about you; it is about your book. So if you’re critiquing something, you might think, “Boy, this guy’s a lousy writer” but never say it. It only makes the other person angry, defensive or hurt. Plus, it makes you look like an ass.

Okay, so you’re done reading a friend’s manuscript. Or you’ve been doing your part in the weekly critique group. You’ve been kind, you’ve been constructive, you’re offering up suggestions that you think might cause a light bulb to go off over the other writer’s head. And then….

They turn on you. They say you don’t understand their genre. Or that if you’re missing the plot points. Or that they intend for you to hate the protagonist. Or that second-person omniscient is the only way the story can be told. I call these folks the Yeah Buts. “Yeah, but if you keep reading, things will get clearer.” “Yeah but if you read more dystopian Victorian zombie fiction, you’d understand my book…”

You can’t help a Yeah But. Sometimes, they don’t want to hear anything except how great their stuff is. Don’t get angry. Don’t take it personally. You did what you could. Smile and walk away.

As Noel Coward said, “I love criticism just so long as it’s unqualified praise.”

Awesome post, and a subject that doesn’t get discussed much. Or if it does, it deteriorates into complaints about how others don’t critique right.

What I struggle most with critiquing others work is pinning down the weaknesses too finely. I spent two years–not a lot but I developed a fine hand at it–in the publishing industry doing just that. In my head I know it’s not dictating where the other person’s story should go, but even as I write my comments, I know how the other person will take it.

AZ: I completely understand. When I first joined my critique group (all published writers) I was too heavy-handed on giving what I thought was advice until one friend took me aside and reminded me it wasn’t my book. It takes a deft hand to give guidance. And sometimes, you just need to listen to the other person work it out themselves.

Super post! In my hamburger world, it’s called a “Nice Sandwich”:

— Be nice.

— Be critical (but constructive)

— Be nice.

Well done. (the post, not the meat)

You’re welcome. I did this post after my sister Kelly and I were working on one of her short stories and she told me to back off! 🙂 Big sisters can be annoying.

I belong to a face-to-face monthly critique group that we have dubbed the Rumpus Writers–or Rumpi. The name goes back to the very beginning of the group, when the decision was made that we would meet in my basement–my rumpus room, if you will. There are five of us altogether–Donna Andrews, Art Taylor, Ellen Crosby, Alan Orloff and myself–and in the decade that we’ve been together, we’ve never once missed a meeting. There’ve been a couple of months when we’ve realized that there are no free dates common to all of us, but when that happens, we’ll double up on another month.

We’ve actually been granted a panel at Bouchercon next month to talk about how to run a successful critique group.

One element that makes the Rumpi a cohesive group is the fact that everyone is very well published, and each of us has won awards for our work. That means we can stipulate to the fact that everybody’s got chops. What it doesn’t mean, however, is that every submission is ready for prime time. Some are pretty rough, in fact, and because we are all friends, and we have been together for so long, we can be brutally honest with each other.

If the piece is stunning, we’ll say so. Ditto the stunning passage or paragraph. For the most part, though, the critiques are about what’s wrong with the submission. No ego-stroking necessary.

In fact, our next meeting is this very evening.

Ah, I envy you. Since I moved to Tallahassee and Michigan, my old buds at the critique group are the only things I miss about leaving South Florida. We were all published as well, but at various levels and in slightly different sub-genres. But we really meshed well and learned to really trust each other. Punches were never pulled but we were always supportive. I dedicated a book to them.

And say hi to Alan for me! Eons ago, when he was just starting out, he was in one of my SleuthFest workshops where participants had to blind-submit their first ten pages. I remember his story vividly. It was good, great potential, with the usual freshman missteps. He came up afterward and thanked me. Made my day! Better yet, he’s now a successful award-winning author.

Getting and giving criticism in a group or shared situation is tricky. My suggestion is that everyone is given a critique check list. Link below to a suggested starting list as well and the ethics of critiquing which is a must for most groups:

http://mbyerly.blogspot.com/search/label/critiquing

For over thirty years, I’ve worked as a writing teacher as well as doing pro-critiques as a fundraiser for various RWA groups. Not to mention a free book doctor for pro friends. So, yeah. Been there, done that with every type of reaction and expectation from writers. My personal favorite horror is the poor sweet snowflake who tries to get me fired because I’m being “mean” by saying her work of genius has problems. Even fixable problems. The snowflakes are the prime reason I rarely teach these days. What little I make isn’t worth it.

The good news for those who are teaching now is that the snowflakes and arrogant “my work is genius” types are going straight to self-publishing. Not that the one-star reviews and low sales teach them anything.

I’m smiling at your description of dealing with snowflakes. Geez, if you can’t handle a teacher’s input or insights from a critique group how in the world are you going to survive your first Amazon review? I know a few folks like you mentioned — they tried to go the usual publishing route, were told they needed to learn their craft and then they self-published. Result? No sales and bitterness about being blackballed by some cabal.

I appreciate criticism.

If I disagree with it, I praise the Lord and go on to ignore it. Just yesterday, a good friend sent me a response to my first page of my new assassin thriller. “Your readers are going to be more than curious about why [the assassin, an attractive Chinese-American who is still more girl than woman] would buy the tea in the guy’s shop right before she kills him.” Whoa, Sir. Do you not understand foreshadowing?

If it’s valid, I grab hold of it and use it to improve my story. “Might it be better,” a writer friend (one whose credentials impress me, if no one else), “if you move the plane crash forward in the story and dump your brief history of Romania except for the monster-guy’s name?” I looked at it, realized he was right, and dove the plane, a Russian Tuvlov airliner (go figure, hunh?) first thing, taking the monster-guy down, to be the sole survivor of the crash. It was a good suggestion. This friend has a unique philosophy about storytelling: “Mistakes are our friends. They teach you a lot.”

Criticism can be a good thing. Sometimes, it helps you get rid of monstrous people.

Ha! Love your last line. I should have included a graph about dealing with BAD criticism. Not all insights are equal. And you know, you as the writer kind of have a built-in BS detector about it. And yeah, you’re right. Thank the person and then ignore them. This works well on relatives you don’t like as well.

I agree with the philosophy of Jim’s friend: “Mistakes are our friends. They teach you a lot.”

I also like Proverbs 12:1. “Whoever loves discipline loves knowledge, but whoever hates correction is stupid.” Those are hard words to live by, but improvement is rarely easy.

You got me curious and went and read all of Proverbs 12. Such wisdom there for today’s world.

Yeah. Proverbs is self-editing for the soul.

No…I don’t think we need those big fat carb-filled buns on the burger. Why have we come to this? Do we need to add fries and a milkshake as well?

I’m a professional editor, but for the first part of my life I worked in the business world as a computer programmer and website developer (after the Internet arrived). I was there at the very start when there were no classes, no books, we had to learn from others who figured out things we didn’t, and we wrote everything from scratch–literally. We started with a blank screen. We had to design business apps, tracking programs, and websites from our *imagination*. We might have an example of a similar project, but every project was completely customized and unique to each client.

It was like writing an entire book from start to finish, only knowing the main requirements of the project (in writing–the basic plot, characters, and main point), and figuring out how to design all of the rest so the final product worked perfectly and smoothly for the end user (in writing–the reader). We also had to “edit” our programs when we constantly got requests to change or add things. I worked for fifteen companies in a couple of states for almost two decades.

My point: we never expected anything but blunt orders to do the job, no matter what it took (and those in authority had NO clue what it took). If someone gave us negative feedback or wanted it changed, we had to fix it. Period. Even if we had to delete months of prior work and redo everything–which was utter agony, we did it. Period. Of course, we loved it when people said how useful our work was, but that was a rare occurrence.

MANY jobs require imagination, endless hours (weeks/months/years) of personal design, creativity, development, and many of the characteristics of art–even if they also require specialized techical skills. I seriously don’t understand why most writers (and I’m a writer as well, not just an editor) think that editors need to come along with a soft Q-tip to daintily touch up a tiny spot here and there in reverence. I’ve been called a “sniper” as an editor (as a joke by a close author friend), and it was a compliment! I identify exactly what works and what doesn’t. I’m not mean, and I do add honest compliments, but my JOB is to make the book as polished and perfect and successful as it can be.

I don’t know why writers believe they should be admired and praised and adored by the editor they hired to find errors. That baffles me. You have family, friends, a street team, fans, etc. to do that. That’s not an editor’s job. (Or a critique group.) It you don’t want to hear your faults and weaknesses–so you can grow and become an incredible writer–don’t submit your “baby” (such an erroneous term–writing is hard WORK that can be changed and improved on) to an editor or critique group.

I’ve learned that when I’m editing “fragile, sensitive” writers, I need to intentionally add all kinds of nice little comments throughout a book, but it’s not sincere and it’s a whole lot of extra time they’re paying for. Plus, it’s silly. If your vehicle had problems, you wouldn’t hire an expert to admire and priase you and your vehicle–you hire them to check it thoroughly, figure out what’s wrong, and bluntly point out what needs ro be fixed.

Same with hiring an editor for a book or magazine article or screenplay or whatever you write. Search for a professional, experienced editor and exceptional proofreader, and *look forward* to them finding and fixing all the problems. You should be *pleased* that they are doing hours of intense work to make you shine. AFTER polishing and perfecting your work, your readers can honestly give you all of those raving accolades (and burgers and steak and caviar)–because your writing is excellent.

Lora, I think your comment brings out the necessity of identifying different kinds of critique-relationships. An editor hired to make the work of a master (or advance journeyman) writer shine is in a different critique-relationship than a beta reader for an amateur writer just starting out, a new apprentice, if you will.

Belichick is going to critique Brady very differently than a little league coach will critique a nine-year-old. The little league coach is teaching; Belichick is “polishing.” The golf instructor will teach me to keep my eye on the ball until it’s not there any more very differently than Tiger Woods’s coach will jump on him if he starts lifting his head too soon.

I see Lora’s point about not coddling writers. It doesn’t help them grow. But I think Eric makes a valid distinction between those already on the professional path and those who are still unpublished. No pro writer worth their salt objects to helpful editing. Only a fool thinks he can go naked ie be without backup of good editors and copy editors. But someone just starting out needs a different approach. Thanks to all who weighed in.

Pingback: About This Writing Stuff… | Phil Giunta – Space Cadet in the Middle of Eternity