Adapt what is useful, reject what is useless, and add what is specifically your own. – Bruce Lee.

By PJ Parrish

A couple years ago, I decided I needed to get back in shape. I had gotten lazy, a little flabby and sort of depressed about it. So I decided to go to a personal trainer. John was just what I needed — a kick-butt no-nonsense guy’s guy who knew a lot about how the human body worked. He also knew a lot about how the human mind worked.

Or in my case, didn’t work.

It hit me somewhere around the second month of training that my brain was out of shape. I had lost discipline, fallen into bad habits, and was locked into an inertia of inaction.

You probably know where this is going. I am talking also about my writing life.

My writing routine had gotten slack. My output had declined. I was making excuses to not write. I was getting down about the whole thing.

John was big into martial arts, and his hero was Bruce Lee. He talked often about Lee’s discipline and his approach to his “art.” I pretended to listen as I did my curls and crunches. But stuff started to sink in and I did some research on Bruce Lee. Pretty amazing life, that guy. He was famous for developing his own brand of martial arts called Jeet Kune Do. He took techniques from a wide variety of other disciplines and discarded many of the “rules” of traditional martial arts.

But here’s something that really resonated with the writer in me: Before he got to this point, he spent years training in all the traditional styles like karate, aikido, judo. To find his own unique style, he did all the “basic training” and took no short cuts. He was a little like Picasso, who painted this

Before he painted this

Both Lee and Picasso learned the rules and then broke them.

Both Lee and Picasso learned the rules and then broke them.

Writers talk a lot about rules. We here at TKZ talk a lot about rules. Maybe it’s because what we do is not easy to learn, even if you are a “natural.” We go to workshops and conferences, read how-to books, underline passages in Stephen King’s On Writing, looking for tips and techniques to help our writing. We want to get better, always, at what we do. We want to know the rules, because if you learn the rules, maybe you can get in the game.

Don’t use adverbs!

Don’t use passive voice!

Keep backstory under control!

Write every day or you die!

It’s a wonder we get anything down on the page. Except maybe our own blood.

Writer’s rules aren’t anything new. A guy named S.S. Van Dine’s set down his Twenty Rules For Writing Detective Stories in 1928. (“There must be a corpse, and the deader the corpse the better.”) Many other famous writers have been compelled to weigh in with their own lists. Here are a few tidbits I culled:

- Margaret Atwood: Don’t sit down in the middle of the woods. If you’re lost in the plot or blocked, retrace your steps to where you went wrong. Then take the other road. And/or change the person. Change the tense. Change the opening page.

- George Orwell: Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Jonathon Frazen: It’s doubtful that anyone with an internet connection at his workplace is writing good fiction.

- PD James: Don’t just plan to write – write. It is only by writing, not dreaming about it, that we develop our own style.

- Joyce Carol Oates: Unless you are writing something very avant-garde – all gnarled, snarled and “obscure” – be alert for possibilities of paragraphing.

- Ian Rankin: Have a story worth telling.

- Zadie Smith: Protect the time and space in which you write. Keep everybody away from it, even the people who are most important to you.

- Hilary Mantel: Be aware that anything that appears before “Chapter One” may be skipped. Don’t put your vital clue there.

- Henry Miller: Work on one thing at a time until finished.

- Mark Twain: Write without pay until somebody offers pay.

- Richard Ford: Don’t have children.

I can agree with most of that. But then again, I have dogs. There are some rules, however, I found that I can’t endorse:

- Mario Puzo: Never write in the first person.

- Robert Heinlein: You must refrain from rewriting except by editorial order.

- Jack Kerouac: Write what you want bottomless from bottom of the mind.

If someone can explain that last one to me, I’d be grateful.

It used to be that you had to read a book to get advice from the famous on writing. When I first read Annie Dilliard’s The Writing Life, I didn’t learn how to write but I was relieved to learn I wasn’t alone in my self-doubts. But now, thousands of writing tips are available to us at the tap of a finger, and anyone can hang out a how-to shingle. So how do you sift the wisdom from the chaff? I remember when I was first starting out in the romance field, I read dozens of Silhouettes, went to the RWA convention in New York, and searched for the secret formula that would make me rich and famous. I had to learn to write sex scenes, which I hated doing, and back in the 80s, there wasn’t much help on the internet. I could have really used blogger Steve Almond back then. He calls himself “an internationally famous author celebrated for my graphic portrayals of amour.” He wrote a blog detailing his rules for writing sex scenes. Here’s one of his rules:

Never compare a woman’s nipples to:

a) Cherries

b) Cherry pits

c) Pencil erasers

d) Frankenstein’s bolts

Nipples are tricky. They come in all sorts of shapes and sizes and shades. They do not, as a rule, look like much of anything, aside from nipples. So resist making dumb comparisons.

If you want to read his other tips, click here. But be warned, they aren’t all PG-rated.

Rules can be confusing, arbitrary, and deeply frustrating. I guess the only good advice I can offer is what Bruce Lee suggests in the quote at the beginning of this post. Adapt what you find useful, reject what is useless, and find your own path. I’ve been writing novels professionally for about thirty years, and whenever I see someone — famous or not — laying down rules, my hairs go up. Still, I have discovered a few “rules” along the way that I have found deeply useful:

Kurt Vonnegut: Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water. This taught me to dig deep for motivation for every character I put on the page, especially the villains. Later, I heard Les Standiford preach the same principle when he said that until you understand what your character wants, not just on the surface but at his deepest levels, you can’t write a good story.

Linus Pauling: The way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas. This taught me that not every story idea will work. Some are good maybe for a short story. Some are ugly babies that might need a few years to blossom into beauties — ie, you might not be ready to tackle that story at that point in your life or technique. And many ideas are just dumb or dull and you have to let them go. Sometimes you have to drown them.

David Morrell: Know your motivation. I’ve heard David speak at conferences about this and he has lots to teach writers. But this one always stuck with me. Here’s more from him: “Before I start any novel, I write a lengthy answer to the following question: Why is this project worth a year of my life? If I’m going to spend hundreds of days alone in a room, I’d better have a good reason for writing a particular book.” I urge you to click here and read the full post. It’s instructive and poignant.

Ernest Hemingway, who didn’t put his rules on paper, but did confide this to his friend Fitzgerald: “I write one page of masterpiece to ninety-one pages of sh*t. I try to put the sh*t in the wastebasket.”

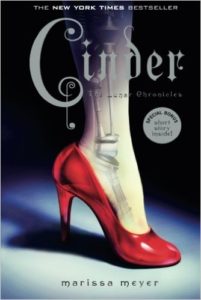

So yes, study the rules. Learn the rules. Many even write a few unpublished stories that adhere to rules and old formulas so you can see the departure point. But then have the courage to break the rules. I don’t read much sci-fi and I don’t read any YA. But this blog was inspired by a story I heard about recently about a debut author named Marissa Meyer. She wanted to write a Cinderella story. Pity the girl…not even published yet and she was breaking a big rule: Don’t rely on stale old plots! Agents and editors want something fresh!

Meyer’s book is called Cinder. Yes, it’s based on the old fairy tale — Cinder is an outcast with nasty stepsisters. She’s also an Asian cyborg. The book became a New York Times bestseller. Why did I like this? Because one of my “rules” is to say something unique or say it uniquely. This is what Meyer did – took something old and made it new and her own. She broke the rule. And somebody came up with a slamming cover.

One last rule. It comes from one of my favorite new-to-me authors:

Neil Gaiman: The main rule of writing is that if you do it with enough assurance and confidence, you’re allowed to do whatever you like. So write your story as it needs to be written. Write it honestly, and tell it as best you can. I’m not sure that there are any other rules. Not ones that matter.

What are some “rules” that you’ve found that work for you? What are the ones that you’ve rejected? And how did the rules help you find your own way?

RE David Morrell’s “If I’m going to spend hundreds of days alone in a room….”

All I could think was, “This is a PROBLEM?” 😎 😎 😎

Joyce Carol Oates quote didn’t make sense to me.

I’ve read many books and articles on writing, taken classes, etc. There have been times in my life that I’ve driven myself absolutely nuts fretting over the rules and being in crit groups where folks obsessively spouted rules–it’s easy to do in a crit group–after all, you want to provide your crit within a framework and what better framework than with oft-repeated rules? That’s not a bad thing except sometimes I get the feeling that critiquers use the rule spouting thing & that they are not deeply thinking about the piece submitted.

At this point, I know rules are there for a reason but I’ve just had to harden myself to not being…well….’ruled’ by them. Rules are great foundations in writing—except when they grind you to a freezing halt and that can definitely happen, especially if you are a perfectionist. Then they’re not so great.

Some great rules to live by in this post, but I vote for Bruce Lee’s as most useful.

Great insights, BK. I like your line that rules are great foundations. And as a recovering perfectionist (can’t sleep unless the towels are folded just so) I get your point that rules can create paralysis. Bruce Lee also said something to the effect of “obey the principles but don’t be bound by them.” Which is good advice.

As always, an informative post (and I’ll come back later, after coffee, for a deeper look).

The one “rule” I’ve taken to heart is Nora Roberts’ “You can’t fix a blank page.”

I prefer “advice” to “rules.” I don’t feel bad modifying advice, but I was brought up to follow rules.

Oh dear…I really didn’t need to hear that thing about the blank page today. 🙂

Terry, that Nora Roberts quote is one I need to print & post prominently. Cuz if you can’t get past THAT rule, you don’t have to worry about any of the others.

🙂

“If you’re good enough, like Picasso, you can put noses and breasts wherever you like. But first you have to know where they belong.” – Alice K. Turner, fiction editor, Playboy magazine

Good one, Jim!

One of my favorite “rules” is this …

“Be courageous and try to write in a way that scares you a little.” ― Holley Gerth

An oldie but still valid, practical advice …

“No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.” ― Robert Frost

I love that quote from Frost, Sue. One of my pet peeves are books wherein you feel like the writer is holding you at arm’s length, unwilling to invest emotion into characters. Maybe it’s a fear of appearing sentimental. But if a book doesn’t move you the writer in some way, how can you expect to reach a reader?

I like the Holley Gerth one.

One I read not long ago that helped me is: Just remember that the first draft is as bad as the book is ever going to be, and if you keep redrafting, one day you will look at your horrible book and realise that you’ve turned it into something actually quite beautiful.

From Robin Stevens who wrote the Murder Most Unladylike series. Maybe this isn’t a rule, but it is certainly true for me.

As a true believer in the power of rewriting, I’m buying this one, Brian. Am also in middle of rewriting first draft now, so it hits home. Every day I am more encouraged because I can see the bad stuff falling away and it’s always thrilling to see what is emerging.

In the painting by the younger (?) Picasso, I’m not sure how many RULES he followed (they seem to change very often in the history of art), but he certainly used a lot of SKILLS. Choosing colors, deciding on layout and composition, employing brush and pen well, capturing facial expressions are not matters of rule-following but of skill–plus TASTE and SENSIBILITY, I think. Even perspective, unless you’re plotting disappearing points on a drafting table, seems to be a matter of skill, not rules.

Everyone knows where the nose goes. That’s not a matter of rules but of observation. Being able to put pencil marks or blobs of paint on a surface to give the appearance of a nose is a matter of skill, not rules. I think that over the years I’ve seen some very good abstract art by people who couldn’t paint a recognizable face if they tried.

I’m not sure how the distinction applies to writing fiction. The important thing may be that appealing to other domains (painting, piano playing) doesn’t necessarily make a good case for learning “rules,” “craft,” “advice,” “reader expectations” in fiction writing.

Does this make sense?

Yeah, I get what you’re saying Eric. I included the Picasso works to make the point that Picasso began as a traditionalist, comfortable in the academic tradition. He could really “paint” in the narrow definition of the word. He painted the picture I included when he was only 15, and it was derided by critics of the day who said the doctor’s hand didn’t look realistic enough, that it looked like a glove. Ha…

He rejected the academic style, which led to his famous blue period (my favorite) and of course all the other riches that came after. Could he have reached his final style without mastering the academic “rules”? No one can say. He was a bridge between the old and the new. His famous quote “It takes a long time to grow young” always meant, to me at least, that it takes an artist a lifetime to sluff off the straitjacket of early schooling. I was an art major and never could do it. I have better luck with writing, but some days are better than others. 🙂 Originality comes hard.

Like BK, I’ve spent time in online critique groups where many people feel that these ‘rules’ are laws. These are the same people who believe that Elements of Style is a book of laws that will send you to hell if you break them. Never use a semi-colon! Never start a sentence with ‘but’ or ‘and’! Never use an -ly adverb!

Me, I read style guides for fun. I have a pretty good understanding of what is forgivable, what is flexible, and what will get you sidelined. Elements of Style is basically a high school understanding of style, but it’s only a starting point. It doesn’t go into the richness of true style. It doesn’t address all the problems one might encounter, and it certainly shouldn’t be used as ‘rules’ for writing.

The only ‘rule’ should be to write the strongest work you can. I’m not saying don’t write passive verbs or even passive voice, but use them sparingly and for effect. I’m not saying don’t write run-on sentences or lengthy paragraphs, but use them to effect. This isn’t a negative rule: don’t do this, don’t do that. It’s a positive rule: Use strong writing. Write to effect.

That’s a good way to look at it, BJ — rules shouldn’t be a strict litany of “don’ts.” If you turn it around, as you did, to the “do’s” it can make sense.

Great stuff today, PJ, thanks (yes, I know your real name, too, but am not sure if it’s acceptable to you to actually use it here on KZ).

Because so many writers swear a blood oath to a “there are no rules” mantra, I’ve learned it all goes down better when we view it like this: “there may not be rules, but there absolutely are principles.” This makes it easier and clearer to paint outside those lines when it serves the story, and the writer.

Thing is,.. too many writers aren’t ready to paint outside the lines. You sort of have to earn the right to do that, through a true understanding stemming from a working apprenticeship over time (that’s the part that those who say “writing can’t be taught” – which is horseshit, by the way – are referring to). For example, at a conference recently a young writer brought me a story that had no conflict, no plot, it was a diary “from the heart” of her heroine, who was simply traveling over the summer after graduation. Nothing happened in the story. This is one of those principles (a set of them, actually) that actually determines what a novel is and isn’t… and this wasn’t a novel. She insisted it was, using Gaiman as justirication (a misquote at that). Then, I asked her what genre she thought her story fit into, and she said it was a romance. No, it wasn’t, because it violated all the “principles” that define a romance.

If one is not writing “literary fiction” or “experimental fiction,” then the principles matter. Doesn’t matter what we call them, they are what they are. Some writers say, “all those rules make me crazy, I have to set them aside and just be me,” and the context of that offering is that they are bragging about this. That this is a more artful approach. Not being able to write within the lines of the principles that define fiction in general and genre in particular is not an asset, it’s a handicap.

Thanks Larry…and yeah, you can call me Kris but my best buds call me Montee. (long story…if we ever bend an elbow together, I will tell you why).

As you say, I’ve got no patience for writers who sing “I gotta be me.”

Yeah, you do. That’s what originally is all about. But if I’m the reader, you damn well better make me really captivated by “me.” The personal is trite and boring. The trick is taking what is personal and making it universal. But that’s another blog, right?

I don’t know what Kerouac’s bottomless comment means, but I suspect Rule #3 – Try never get drunk outside yr own house – had something to do with it.

Bwahahaha! Now THAT makes sense. Thanks, Cynthia.