It is the loose ends with which men hang themselves. — Zelda Fitzgerald.

By PJ Parrish

Another sleepless night. But – hazzah! – another idea for a Kill Zone post. Two nights ago, unable to stop the hamster wheel in my head, I took my pillow out to the sofa, hit the remote, and trolled for a good movie. Nothing except…

The last half hour of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. Now I hadn’t seen the movie since it came out in 1989 and while I didn’t remember all the characters and plot points, I did remember that climax. And that is where I came in the other night, right when the tensions and heat in the Brooklyn neighborhood boiled over, leading Mookie to throw a trash can through the window of Sal’s pizza joint. All hell then breaks loose.

Spike Lee choreographs this climax with chilling precision. But what interested me was what came after. The next day, Mookie and Sal, standing in front of the smoldering ruins of the pizza joint, argue then reach a tepid reprochement. But Lee adds a coda of the local DJ (Samuel Jackson) greeting his listeners with the admonishment “Wake up! Up you wake, up you wake, up you wake! It’s gonna be another hot day.” Then before the credits roll, Lee gives us two quotes — from Martin Luther King Jr. on peaceful protest and Malcolm X on violence as self-defense.

That’s when I got up and jotted some notes for this blog. Because I think the ending of Do the Right Thing is a great departure point for a talk here about the dénouement.

De-noue-what?

You’ve probably heard this term bouncing about in craft books or maybe on conference panels. But I’m not sure we really know what it is or how we should use it in our books.

First, let’s learn how to say the sucker: It’s day-new-moh.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dXbsK7eHirk

It comes from the Old French word desnouer, “to untie” and the Latin word nodus for “knot”. It’s the part of the story that comes after you’ve built up your conflicts in a rising arc of tension and blown up your plot in a giant fireball of gun fights, car chases, lovers’ quarrels, dying zombies or melting Nazis (I also watched Raiders of the Lost Ark this week). The dénouement is what comes after the climax, wherein you the writer have to tie up those loose plot ends, slap on some salve, leach out the suspense and resolve things into a nice satisfying conclusion.

Or maybe not. But we’ll get back to Spike Lee in a second. For now, let’s stick with conventional dénouements.

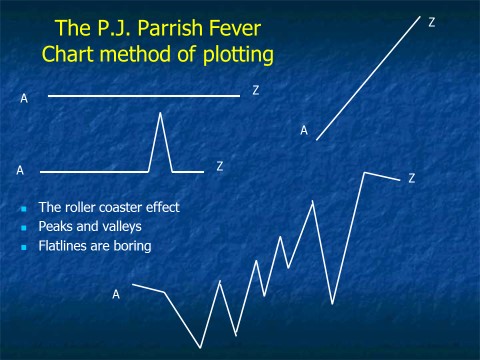

Above is a slide from one of our workshops. We’re making the point here that a good plot is never a flat line or even a comet-shot straight upward. It is like that fever chart at the bottom — a series of triumphs and setbacks for your hero but its main thrust is always upward toward the climax. And that little downward line out to Z is just the denouement.

Think of the dénouement as a coda to the big movements that precede it. It is a tail on the plot beast, but still important because it is where things are explained (if necessary) and secrets revealed (sometimes). Shakespeare was big on dénouements: In Romeo and Juliet, after the lovers are dead, the Montagues and Capulets gather and Escalus lays a big guilt trip on them all telling them their feud is to blame. At the end of Hamlet, with the stage strewn with bodies, Horatio shows up to remind us that the voices of angels will carry Hamlet to his heavenly rest, meaning his story – and thus he – will live forever.

To use a metaphor: Your climax is well, like a climax. The dénouement is smoking the cigarettes afterward.

Maybe it’s useful to stop here and think about the THREE-ACT STRUCTURE. James and others here at TKZ talk about this a lot, so if you aren’t familiar with it, pick up James’s books on plot structure or go troll through our archives. Here’s the skinny over-simplified: The first act is your set-up wherein you introduce characters and their world, set up your plot, and define the main conflict that is the hero’s call to action. The second act is “rising action,” a series of events and setbacks that build up to the climax. The third act is the turning point and climax that requires the hero to draw on strengths, confront the antagonist and solve the problem at hand. Then we move into “resolution” where conflicts may be fixed, normalcy restored, and anxiety (for the reader) released.

The dénouement is a big deal in traditional detective stories. You will often get at the end of the story Holmes or Poiret laying out the clues and explaining how they figured things out.

One of my favorite detective dénouements is from Psycho. The climax has Norman, dressed up as Mother, trying to stab Lila in the creepy cellar. But what comes next is the scene in the courthouse where the psychiatrist explains what happened to Norman.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=abAsTTC9puk

It’s hokey, yeah, but we need to understand how Norman got so twisted. Likewise, you might need such a useful scene to help untangle the yarns of your plot at the end.

My sister Kelly and I are struggling with this notion right now with our WIP. We’re at the climax wherein our hero confronts the bad guy and triumphs, of course. The bad guy has to die. But we realized that while we knew why our antagonist had rotted from within (and you need to know this!) we had no one in our cast of characters to explain it to the reader. Yes, the hero can surmise things about the bad guy, and you need to sow the clues of personality throughout the story. But sometimes, in the end, someone — like the shrink in Psycho — has to give it context and history. So we went back and inserted a new character early in the book — hidden in plain sight — who will, in a denouement, give testimony.

There’s a great example of dénouement in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. After the climatic fight between Biff and Willy and Willy’s suicide (to get insurance money) there is a final scene called “Requiem” where the family gathers at Willy’s funeral. Sadly, no one has come to pay their respects. Biff laments that Willy had “the wrong dreams.” And Willy’s wife, who has been able to cry, breaks down, sobbing that the house is now paid for, repeating “We’re free…we’re free.”

Both Terminator movies have nice dénouements. In the first one, Sara Conner in her Jeep, guns and dog in tow, pulls into a last-stop desert gas station where a young boy points to the darkening sky and says “a storm is coming.” Sara’s last line before she heads off toward the apocalypse — “I know. I know.” In the sequel, the dénouement is the “good” Terminator lowering himself into the fire pit to destroy his microchip and thus save the world.

Another of my favorites is from The Shawshank Redemption. After Andy Dufresne escapes from prison and disappears, the story is essential over and all is resolved. But no…we are treated to his friend Morgan Freeman’s touching narration about going free: “I hope the Pacific Ocean is as blue as it is in my dreams.”

We can debate this, but I think a denouement is different than an epilogue. An epilogue is an animal unto its own world, a specific literary device that has a special purpose, often yoked with a prologue. The denouement usually takes places immediately following the climax and resolution; an epilogue is usually separated by time — week, months or years later. Sometimes it hints at a sequel to come, or it serves as a commentary of sorts on what has happened. It might sum up what happened much later to the characters. Think of way George Lucas used this device in American Graffiti — as the credits rolled, he shows graduation pictures of each character and listed what happened to each i.e. “Curt Henderson is a writer living in Canada.”

A good denouement is subtle. What you don’t want to do is end up with an extended “Now I have to explain why I have to kill you” speech. This is not a true denouement; this is just a bad climax. The skeins that you weave as you move through your story should come together in a logical and satisfying pattern. And if you have some little loose threads that might poke out after that — well, that’s what the denouement is for.

But then there’s the big question: Do you have to untie every knot? Do you have to snip off every loose thread? No, of course not. I love ambiguity in endings. I don’t like anal books that clean up everything. And truth be told, I don’t really enjoy those classics mysteries where the detective gathers everyone in the dining car and lays it out there. I want to figure some things out for myself. And I crave some messiness in my fiction. Not all stories are neat; not all storytellers color within the lines.

Which brings me back to Spike Lee and his denouement for Do the Right Thing. It doesn’t tie up anything in a pretty bow. In fact, Lee rejects the whole idea of traditional closure. Mookie and Sal are left in a wary face-off that personifies the unease of race relations in general in this country. The mayor (Ossie Davis) tells Mookie to “do the right thing” but no one in this story really knows what that is, which is the only thing that is clear at the end. So what can Spike Lee leave us with except the denouement he offers — two powerful and deeply conflicting quotes from King and Malcolm X. And a final picture of them shaking hands?

Some knots just defy untying.

PJ, you make a good point about tying everything up neatly. It’s great to answer most of the questions that the manuscript (talking about books here–not much of a movie guy) poses, but answering them all at the end can be awkward. I recall being told that some years back (by one of the KZ authors) there should be one or two things the reader has to decide for himself/herself. Thanks for this post.

I agree, Richard. I wrote a post here a while back, sort of a plea for ambiguity in fiction. Maybe it’s more helpful to think of the denouement as a sort of rest after the big action of the climax. Sort of like on a roller coaster ride how the train glides back into the station after the frenetic ups and downs.

Excellent post. I agree it’s not necessary to clear up every mystery or conflict in your ending. Knowing how much to explain and how much to leave in limbo is that sixth sense a writer must develop over time.

Well put, Mike, about that sixth sense. And every story is different, of course. Some need more tidying up than others. And a few cry out for little or no resolution. Which, I think, might be different than satisfaction or catharsis. Can you have a story with no true resolution that still provides catharsis for the reader? Not sure!

Give me ambiguity, or give me something else!

Good food for thought, Kris. I do think genre matters. The more you move toward “literary,” the more some ambiguity will be accepted…though note that literary doesn’t sell as well as the aptly-named “commercial,” which almost always demands a firm answer to “Who won?”

Your Terminator example reminded me of an old Hollywood scriptwriting adage: “Skate fast on thin ice.” That is, where the explanation really doesn’t make sense, or can’t, figure out a way to get through it fast and then move on.

That happens in The Terminator at the end, when Sarah has to try to explain the inexplicable, and so says, “Should I tell you about your father? That’s a tough one. Will it change your decision to send him here…knowing? But if you don’t send Kyle, you could never be. God, you can go crazy thinking about all this…”

Ya think? So move on! And she does. (Time loop movies always have this problem. I very much enjoyed the Cruise “Edge of Tomorrow,” but a moment’s thought at the end will tell you it can’t be so … but by then they’re rolling the credits!)

Ha! Loved your note about Sara’s speech about Kyle. Exactly…it makes no sense but do we really care after such a fun movie? James Cameron has a thing for endings like this. Like, c’mon…do you really believe that old lady is going to throw that necklace off the ship at the end of Titanic after hanging onto it for 80 years? Nah…

Endings don’t get any more ambiguous than the final scene of “The Sopranos.”

It frustrated me at the time, but I later came to love it. the question of what happens when Tony comes out of the bathroom stays and stays, and causes the story to live on long after it’s over. We writers should be so lucky.

Yeah, but what about Lost? Ahhhhh!!!!

Lost was just a hot mess. And they knew it.

So true!!! What a horrible way to end a great series.

Another great column! I just love your writing advice–among the very best on the web. I hope you’re gathering these columns for a future book!

Wow…thanks Sheri. Actually, Kelly and I have accumulated our posts in a book but we only self-published it and give it away at our workshops because we use examples and photos that we don’t own. Slight copyright problem there. I have a whole shelf of these books in my home office. :))

Excellent post!?

Thank you

dontmentionit, Tom! Thanx for dropping by.

I somehow missed this post yesterday, but I wanted to tell you how much I liked it. I’m a fan of the denouement (differing from the epilogue). Some of my favorite examples are the Harry Potter books. There’s something about a climactic battle followed by a mentor assessing your efforts while alluding to situations to come. I might not like that scenario as much in a standalone novel (probably because there won’t be more problems to come), but for a series? It really works for me.

Wow. I can’t believe I almost missed this post. I agree with you. When a denouement is too tied up, I cringe. Thank you for including how to pronounce the word. Apparently I’ve been saying it wrong for years.