By Larry Brooks

Somewhere out there in Kill Zone reader land is a new writer with a wrinkled forehead going, “say what?”

It’s irony, of course. Simple word play. My little attempt at a clever hook. Novels usually don’t have a table of anything, context or content… so what the hell?

But it’s an honest, straight-forward question, as well.

How is the contextual state, the flow, of your novel?

This is one of those issues of craft that can hike you up the learning curve quickly. Like, on steroids kind of quickly. It is something experienced professionals know and practice—even if they don’t associate it with the word context, or (in some cases) without even realizing it—and thus, it remains one of the less politically-proper but nonetheless powerful nuances of craft that is almost always evident in a good novel.

It has to do with story structure.

The context of story structure. Allow me to break it down for you.

You’ve heard of three-act structure. You may not like it, but in genre fiction by a professional it’s almost always there. Don’t mess with it. It is far more fundamental than it is optional.

But that term—three-act- structure—can become vague when you sit down to try it. There is actually more to it than three parts, each of which has its own infrastructure and unique criteria.

I’ve seen story structure broken down into as many as nine parts. All of them aligned with, as sub-sets, the same three-act structure model. Virtually all story structure models have something to offer… as opposed to a denial of story structure, which offers only frustration.

Because the second of those three “acts” is rarely broken down all that succinctly in terms of a functional mission (other than the presence of the all-important mid-point story milestone) beyond the word “confrontation,” I’ve taken a swing at it within my own work (beginning with my book, Story Engineering) in a way that I believe is more useful.

Act II (of three-act structure) actually consists of two roughly equal-length sequences of scenes (quartiles), separated by the all-important mid-point milestone. In fact, it is the way in which that mid-point milestone changes the mission of the quartiles before and after that becomes… context.

Different contexts.

Each of the four quartiles within a novel has its own unique context.

This doesn’t replace or trump three-act structure (okay, it does, because it provides more guidance than simply, “now write Act II”). It simply clarifies it while empowering it.

Let’s define context in this… well, in this context.

Think of a college student pursuing a specific major, in quest of a career to which it will apply. Each of the four years of that requisite curriculum is different. It has its own content, its own context, all of it feeding and building toward the big picture of the major—the whole story—itself.

The freshman is doing something that is orders of magnitude different—in purpose, in content if not form… in context—than is the junior or senior with the same major.

While perhaps simplistic at a glance, consider the challenge of writing a novel without understanding this. Which is actually the sad state of affairs out there, and at all levels. In fact, this helps explain why such a small sliver of novels actually get published, or succeed when they do.

Because, if nothing else, this is a qualitative principle.

Better to know than to guess, or to rely on your current state of story sense (which is, in fact, the degree to which you truly grasp the nuances of all this, no matter what you choose to call it, and no matter what your writing process).

Four parts to your story, each with its own contextual mission.

Each with its own unique narrative contribution to the story. Each with its own unique criteria. If, for example, you’re still doing the work of the first quartile setup (which means, you need to know what that work is… do you?) when you’re solidly into the second quartile hero’s response context, with a first plot point core dramatic arc launch in play (which it wasn’t, back in that first quartile), the novel isn’t working right.

This sequence of evolving contexts is what creates story setup, escalating pace, increasingly compelling dramatic tension, character arc, confrontation and ultimate resolution… all of it in the right places, at the right times, with optimum effectiveness.

All of it, hopefully, in context to a conceptually-fueled premise that gives the story chops in the first place.

Or you can just wing it. Hey, there are only about 112 different moving parts and nuances within a novel, you don’t need no stinking principles, right? This is art, after all. Suffering isn’t optional.

Actually, it is.

If you aren’t aware of this contextual facet of storytelling craft, winging it is your only choice. Wing it wrong, or wing it poorly, chances are your story won’t work, or at least not as well as it could or should work.

That guy who tells you that story trumps structure? It does… for him, and those at his level. Probably not for you. Because you probably don’t know what that guy knows… because he knows all about this contextual sequence of four parts. When a story pours willy-nilly out of his head, this is how it spills onto the page. Not remotely nilly-willy at all.

Not remotely nilly-willy at all.

For newer writers trying to do the same… well, that’s why The Kill Zone is here. To put your storytelling muscles on steroids through the injection of principles into your process.

Once you own them… go ahead, tell everyone you just sit down and write, from your gut, from your instinct, from the seat of your brilliant pants.

Stuffed into those pants will be a big old bulging package of craft and principle… and nobody has to know.

Here’s the rundown of the four sequential parts of a novel, in any genre, roughly defined by quartile:

- SETUP Quartile

The goal here is to build empathy for the forthcoming hero’s quest through foreshadowing, backstory, a life-before-the-drama-explodes into it, and the teeing up of the full launch of the core dramatic arc to come… just not quite yet.

That turn comes with the all important “first plot point,” is a story milestone that moves the story from the Part 1 setup quartile into the Part 2…

- RESPONSE Quartile

… in which the hero responds to the FFP’s launch of the core dramatic arc, via the expositional contribution of that first plot moment story turn, followed by…

… the midpoint story turn, where the context shifts again, based on new awareness and motivation (stakes) on the part of the hero… into the…

- ATTACK Quartile

… wherein the hero leverages everything she/he has learned and seen and the way in which the midpoint changes the context of the story, now with more direct confrontation and proactive attack on the goal (instead of reacting and running, they step into the pursuit of what is needed to resolve the story), the problem and the antagonist that stands in their way…

… leading toward a second major plot turn, in which the story changes yet again in a way that thrusts the hero (and possibly the antagonist) toward an irrevocable date with destiny via a final battle of wits and strength, using courage and cleverness and strategy (rather than anything close to luck or a dreaded deus ex machina), all of which is the stuff of the…

- RESOLUTION Quartile

… in which the scenes build toward a brilliant, dramatic and emotionally-powerful culmination, and from there, launching the hero back into a life that is different (because the hero is, in fact, different) than before.

Four parts. Four contexts of narrative exposition.

The opportunity in this is significant.

This guides you toward writing the right scenes and putting them in the right places, thus optimizing pace and keeping the story soundly on track. Instead of (here comes a menu of risk and rookie mistakes): a lagging open, changing lanes, diversion and non-relevance, thematic preaching, too much backstory (because, really, the Part 1 setup is the only real place for much substantive character backstory), waning pace, lack of character arc or proactive action, and most of all, a too-vague unspooling sense of dramatic tension.

Dramatic tension itself is a context. Foreshadowing is a context. Exposition is a context that must be managed. A virtual banquet of context to serve up the meal of your story.

Which is why I ask… what is the state of your table of context?

Now you have a tool, a model, for doing that, in all these contextual realms.

Critics of this rail against it as formulaic. When I claim the story probably won’t work well without it, as I do in my writing books (and by the way, my brother-in-arms James Scott Bells agrees on that count)—cynics and old school resistors claim that’s just me blubbering heresy in the form of formula… as if there are other options.

But guess what: genre fiction is inherently formulaic. Success resides in the creative power with which you harness the formula (hey, I don’t like that word either… so let’s call it a structural principle and get on with it), rather than trying to invent your story form of storytelling.

Those “other options” may appeal to you early in the story (a form of siren song calling to you), but when you get the feedback that the story isn’t working, often for specific reasons, the “fix” to that is, almost invariably, to move the story back closer to this four-part, contextually true form after all.

And then—if you continue to deny what just happened—it’ll be your ability to revise, rather than the principle saving your creative butt. A principle that was there all along, waiting to empower your first draft (once you truly have wrapped your head around it, as, say, Stephen King has… yes, the King of All Pantsers knows this, it is precisely why his pantsing process works him) as much as it will empower your revision draft.

When writing gurus tell you to just write, to use your first draft to find your story… know that with these principles in your head, you’ll find it faster, and better.

It has nothing to do with process, in terms of planning versus pantsing. Rather, it has everything do with knowing how a story should unfold… what goes where, and why.

What a story is.

If this is new to you—and especially if you doubt it—I recommend you test this revelation.

Grab a bestseller, read it analytically… and behold the four contexts of the four quartiles unfolding before you like a curtain parting to reveal the author’s machinations and the power of these principles before your eyes.

It’s the way story works, at a professional level. It’s empowered story sense. Versus the rather clueless one we all began with, back when all we brought to the party was our experience as a reader, all before an immersion into craft changed everything.

*****

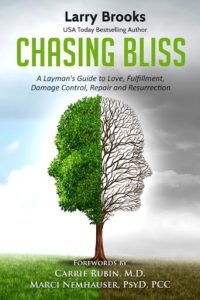

As a side note… I just published a non-fiction side project, called CHASING BLISS: A Layman’s Guide to Love, Fulfillment, Damage Control, Repair and Resurrection.

This, too, is driven by context-informed principles. And like writing, it can take a lifetime to understand if you try to make it all up as you go along.

I’ll write more about this in two weeks. For now, only the Kindle is online at Amazon; the paperback will be available there in about 6 days, once the self-publishing machine works its wondrous, laborious ways. (It’s already in the Createspace bookstore.)

This is great information on context in a novel and the types. I never knew there are 4 types in it. Doing what you just mentioned here: “Grab a bestseller, read it analytically… and behold the four contexts of the four quartiles unfolding before you like a curtain parting to reveal the author’s machinations and the power of these principles before your eyes.” I’m sure I’ll be surprised.

THanks Tom, glad you found this valuable. Look closely in the genre books you read, you’ll see those contexts in play over these four sequential parts of the story. Wishing you great success!

Critics of this rail against it as formulaic

I tell my workshops, try to make an omelet with a watermelon. What? You can’t? You mean there’s a formula (called a recipe)?

But what makes an omelet unique? It’s the spices and cheeses and veggies and meat you include, which ones and how much. Maybe a bit of habanero sauce, but not too much! (That’s called art)

There is a pattern to story so it connects with readers. But writers get to choose the spices, cheeses, veggies and meat (characters, scenes, dialogue, voice, etc.) Learn how to make an omelet first, then play all you want with the taste.

Omlettes… gotta add that to my analogy quiver, Jim. It’s pretty full, as is, but this is a good one. Thanks for weighing in!

Larry and Jim Bell. The top of the pyramid!

I love the analogies in this post–and in Mr. Bell’s comment. Four years of college. Following a recipe.

Examples like these make the concepts easier to understand. And they are extremely important concepts for writers to grasp.

The leader of my writing group often suggests taking a novel and analyzing it for structure. It’s a great way to see the framework that supports the story.

Good tio hear. Not all writer/reader/students appreciate analogies. But I have to admit, sometimes I over-kill them, so that’s on me. Good that you “got it” today.

I love the way you’ve distilled writing a book to “writing the right scenes and putting them in the right places.”

Piece of cake!

Hey, another analogy for us: piece of cake! Lots of layers, different flavors, and the need for an aesthetically pleasing look and design on the outside. Oh, lots of calories, too… gotta keep our readers fat and happy. ☻ Thanks for weighing in today!

Pingback: The Critical Essence of "Context" Within Your Story - Storyfix.com

I’ve never seen this structure before. You’ve given me lots to think about. One plot element that I’m fond of is “the dark moment” when all seems lost for the protag. (I like an underdog.) Conceptually, that might normally be included in the Attack Quartile, but how do you see that fitting into your 4 plot shifts?

Thanks, Larry.

Hey Jordan, this is a terrific question. Like much of the structural discussion, there are options and soft-edges and story-specific needs that lead us to answers.

The “dark moment” is usually, in classic structure, at the end of Part 3, right before the Second Plot Point (targeted at the 75 to 80th percentile mark). Remember in the movie Tombstone, when Kurt Russell is being run out of town by the Clantons, tail between his legs? That’s the dark moment, right before the 2ndPP. In the next scene Russell surprises and nearly kills Billy Clanton at the trian station, and against backlighting from the moon and flashing lighting, pulls back the collar of his duster to reveal his shiny new deputy badge, and tells the quivering Billy (literally under Russell’s boot at this point), to “tell ’em hell’s a comin! Tell ’em I’m comin’,”

And from there, we head right into the Part 4 resolution quartile.

Classic dark moment, right before the second plot point.

There are other dark moments in a story, at the author’s option, of course. But making those choices in context to an understanding of these structural context is the opportunity, because we no longer need to depend solely on guesswork or instinct, when our instinct is driven by (backed by) the principles of structural craft itself.

Hope this helps.

Great explanation & example, Larry. Thanks.

I have a somewhat (but not totally) off-topic question, Larry …

I’m writing short stories, and I struggle to find similar technique books and articles about short fiction. So I read articles here at TKZ and other writing sites, (I always enjoy articles such as yours and Jim Bell’s), and I’ve bought and read a variety of writing books, including yours, Mr. Bell’s, those by Jack Bickham / Dwight Swain, and Donald Maass, and then try to apply those principles to my shorter works, but not always with great success.

So here are my questions — does this same “structural principle” also apply to short stories? In the same way, or with some variation?

Thanks!

Rick B.

Another good blog, Larry. You’ve made a complicated topic seem deceptively simple.

Last night I was re-watching the movie “Night Moves” with Gene Hackman. It’s a great little thriller well acted and engrossing. The run time of the movie is 100 minutes. The first plot point, the middle crisis, and the second plot point were right on the minute at 25, 50, 76 minutes. And the ending was great. On top of that, the context of each section was right on. Loved it.