Credit: From the site TVtropes.org

“The rain was comin’ down like all the angels in heaven decided to take a piss at the same time. When you’re in a situation like mine, you can only think in metaphors.” — Dick Justice, Max Payne 2: The Fall of Max Payne

By PJ Parrish

Maybe I’m just hanging around the wrong people these days.

I’ve been lucky to have some free time this month so am reading for pleasure. But have started and put aside four books. It didn’t dawn on me until this week why: The protagonists are all hot messes. Maybe it’s because I see enough losers in real life that my patience with fictional ones has snapped its last thread. Coupled with the fact that every character on TV seems damaged, deranged or just too ditzy to live.

Now, we all love a flawed protagonist. Their personal journey is a parallel track that runs along side the main murder plot and creates interest and empathy. But man, does everyone have to be addicted, divorced, friendless, childless, and beset with demons from their screwed up childhoods? Do we really need another detective whose only steady relationships are with Cutty Sark and John Coltrane?

I really wish I could name names here because I hit some passages that are really worth quoting to make my point. And none of these books are old noir. Each is of recent vintage and a couple are big-name writers.

This all dovetailed with a recent Facebook post by my writer-friend and Shamus winner Rick Helms. He’s on a cruise with lots of time to read, but he, like me, has lost patience. To quote:

[I’m] relaxing with a generally well-written private eye novel by a writer new to me. Like many PI novels these days the protagonist is almost painfully damaged. Whether it’s alcohol, drugs, gambling, or just plain paralyzing depression or grief, a large segment of the mystery writing community frequently writes broken protags. Some of these characters have been very critically successful. I have sort of a different take. I tend to regard emotionally damaged protags as a bit of a crutch.

Sure, I’ve written them…[my PI] Pat Gallegher is a gambling addict dragging half a century of failure behind him like a Dickens ghost. My small town police chief Judd Wheeler has PTSD and panic attacks. My forensic psychologist Ben Long presents with a dramatically exaggerated version of my own high-functioning autism. In each case, however, they are coping adequately with their difficulties. While they may experience distress, they don’t wallow in it. None of them wakes up hung over to a living room strewn with pizza boxes and beer bottles and days of dishes piled in the sink (the universal literary language for desperation and giving up). They are managing well despite their problems. Their personal tragedies impact their lives, but they aren’t the story itself.

Rick goes on to say he’s old enough to remember reading the lastest new releases by Ross Macdonald and his own work is influenced by Chandler, Robert B. Parker, Brett Halliday, and the like. He, like me, has a special love of Macdonald. To quote:

Lew Archer TOLD the stories of his investigations. He never WAS the story. The pathos and distress in his stories were always portrayed by the people he interviewed in the course of his investigations. He regards a murder victim or an oil spill in Santa Barbara with the same dispassionate observations as he might describe a businessman’s special baseball game. Archer is an observer of tragedy, seldom reacting to it with more than average empathy. He cares, but he doesn’t lose himself in his investigation. In the end, he walks away with little observable growth or change in his basic character, because he was never broken in the first place. The story was never about him. It was about solving the case.

He also cites Parker’s Spenser as a relatively mentally healthy and confident guy doing a tough job while maintaining a long-term relationship. He cares about people, but — with the possible exception of when Ruger nearly killed him in Small Vices — he rarely allows his own personal condition to do much more than put a hitch in his giddy-up.

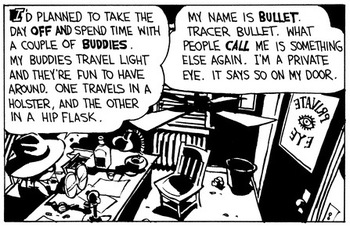

Likewise, as Rick points out, “We know little of Phillip Marlowe’s inner emotions and mental functioning. We know his opinions, because Chandler was full of them, mostly of the sardonic variety. But nobody would refer to Marlowe as damaged.”

When did the shift to a protag’s personal journey begin? I’m not well-read in the old stuff to even guess. But I do know I’m weary of the dreary dick. Is it time to call them out as the tired cliches they are?

Okay, we have to stop and back up. Time for definitions. I love definitions. They bring clarity to fuzzy topics like this. Is a cliche the same thing as a trope? Or is the latter just an uppity word for the former? Lemme give it a go:

Cliche: Using certain phrases, expressions, devices, or archetypes that have been used so much they lose freshness. Maybe they were once intriguing, but when readers see something too often, they become desensitized, and the idea no longer carries the currency it once had. Examples: the naive female rookie patronized by boss and colleagues. (Tyne Daly, playing clean Kate to Eastwood’s dirty Harry?) The slimy defense lawyer. The good-cop-bad-cop. The crabby lieutenant who suspends a rogue underling. The PI who gets the crap beat out of him but jumps out of bed the next morning all dishy and doodle. Add your own to the list…

Trope: A familiar character type, plot point, setting, or writing style that has become instantly recognizable to readers. Very common in genre novels and when done well, every effective. Examples: In the romance, “enemies to lovers” trope (lifted from Jane Austen). The lone gunslinger and embattled sheriff. (Come back, Shane!)

Most folks conflate cliches and tropes but they are distinctly different. Tropes can be good things, helping a character to come across as an old friend or making classic situations feel fresh again (think Romeo and Juliet transformed into West Side Story.)

Time for some Joseph Campbell here. In his The Hero With a Thousand Faces, he drew upon works by psychoanalyst Carl Jung to develop recognizable literary archetypes. According to Campbell, everyone from Homer’s Odysseus to Neo in The Matrix is living out the same epic story. George Lucas credits Campbell for the Star Wars trilogy, using the King Authur trope to create boy-king Luke Skywalker, who gets a magic sword, is guided by an old mentor, and storms a castle to save a princess.

One of my favorite tropes is Austen’s Mr. Darcy. He’s handsome, mysterious, sexy. I loved how Helen Fielding used him in Bridget Jones’s Diary: “It struck me as pretty ridiculous to be called Mr. Darcy and to stand on your own looking snooty at a party. It’s like being called Heathcliff and insisting on spending the entire evening in the garden, shouting ‘Cathy’ and banging your head against a tree.”

Let’s face it, crime fiction is at its heart tropian. We rely on situations (crimes, usually murder), archetypes (loner cop holding out for justice) and even some “rules,” which of course can be broken.

But how do you honor the great traditions of our genre without being banal? How do you cleave to such a well-worn path and still give your readers some new vistas? How do you utilize trope and not slide downhill into cliche?

Our dilemma is that a story has to feel new and yet be familiar enough to be recognized as part of the genre. Writers often want to pay homage to their favorites from the past, but characters have to distinguish themselves in their own present or they petify into stereotypes. In the early books, Spenser seemed a Marlowe knockoff, but Parker quickly made him into his own man.

Years ago, I got into a lengthy blog discussion on this subject with a bunch of crime writers. Luckily, I kept this quote from Brian Lindenmuth: “the PI novel is the haiku of the mystery genre; there may be only 17 syllables but in the right hands those syllables will sing. There is the potential for a lot of power in that framework.”

I liken crime writing to classical ballet. There are only five positions for the feet and arms in ballet. But within that strict framework, anything is possible, from swoony-romanticism of Swan Lake to George Balanchine’s Stravinsky-twitchy Agon.

The trick, if it can be simplified as such, is that you have to take our beloved tropes and turn them into your own, like Fielding did with Emma and Bridget Jones. A while back, I contributed a short story to an anthology whose theme was honoring the PI tradition. Being on a John D. McDonald binge back then, I decided to create a female McGee whose business card read: Mavis Magritte, Salvage Consultant, Slip C12, Duncan Clinch Marina, Traverse City, Michigan. I had a ball writing that thing. Mavis has to prove her best friend Eunice Meijer didn’t kill her creepy lover Dirk. And yes, they drink gin.

Trope on, crime dogs. In the meantime, take some inspiration from the pas de deux from Balanchine’s Agon.