I never thought I’d live this long. I turned 65 on Tuesday. Officially, I’m a Senior. I legitimately qualify for sympathetic elderly discounts, and I’m gonna pocket the 10 percent—not feeling the least bit guilty over getting geezer graft.

I’ve made 65 trips around the sun. Some were easy. Some were hard. One year, I survived three fatal gunfights within two months—one leaving my police partner and best friend dead beside me. And I witnessed two miraculous childbirths within three years—our daughter Emily and our son Alan—one of whose delivery was not at all easy on my wife Rita’s body.

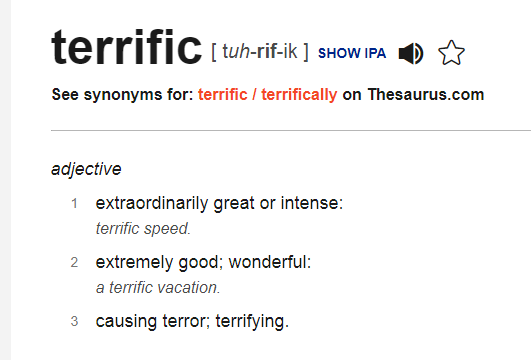

Many of my life experiences, from trauma to triumph, were terrific.

Some I’d love to relive. Some I’d like to reverse. But I’m happy, very happy, to be here and continue enjoying life.

I guess I’ve lived this long because, despite the odds of succumbing to high-risk behavior, the Creator purposely let me trip 65 times around the sun and learn a few bits. I believe in the Creator, and I believe the Creator approves of me passing-on these 65 bits from 65 trips.

——

- Whatever the mind can conceive and believe it can achieve by taking action with a positive mental attitude. This is the core of Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich personal growth and success philosophy which, in my experience, is pure truth.

- You become what you think about most of the time.

- Be careful with your thoughts, because your thoughts become your words. Be careful with your words, because your words become your actions. Be careful with your actions, because your actions become your habits. Be careful with your habits, because your habits become your character and your character becomes your destiny.

- Dream big. The first step in achieving a big dream is by having one.

- It doesn’t matter what came first—the chicken or the egg—as long as you stay alive and remain healthy enough to eat them.

- I’ve been rich. I’ve been poor. Rich is better.

- Always read the instructions. Twice. Then save them.

- Don’t buy extended warranties, timeshares, or cheap tools.

- Persistence is to character as carbon is to steel.

- If you must read the news, read for fact and data, not for opinions.

- Murder doesn’t round out anyone’s life except the murdered’s and sometimes the murderer’s.

- When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.

- If you chase a badger across a field and it goes down a hole, don’t follow and poke its backside with a pick handle. Seriously, I tried this and it wasn’t good.

- People of accomplishment rarely sit back and let things happen to them. They go out and happen to things.

- Do not steal the parking spot reserved for the guy who’s about to interview you for your dream job.

- And don’t bother searching for your eyeglasses while wearing them.

- Speaking of eyeglasses, when you go searching for your glasses and finally find them, don’t put them back where you found them. Put them where you first looked for them.

- Once you get it all down to one shopping cart, you’ve got it made.

- The Golden Rule will never fail. It’s the foundation of all other virtues.

- I don’t judge your age, race, gender, sexual orientation, language, religion, political beliefs, education, occupation, body shape, or any other thing that makes you as a human being. You are you. I am me. I’ll be nice to you even if you’re not nice to me and I’m okay with that.

- Never get involved in an Asian land war.

- To make mistakes is human. To own your mistakes is divine. Nothing elevates a person higher than quickly admitting to, and taking personal responsibility for, the mistakes you make and then fixing them fairly. If you mess up, fess up. It’s astounding how powerful this ownership is.

- Optimize your generosity. No one on their deathbed ever regretted giving away too much.

- I’ve never seen a hearse pulling a trailer loaded with a ski-boat, an ATV, or a full-dresser Harley.

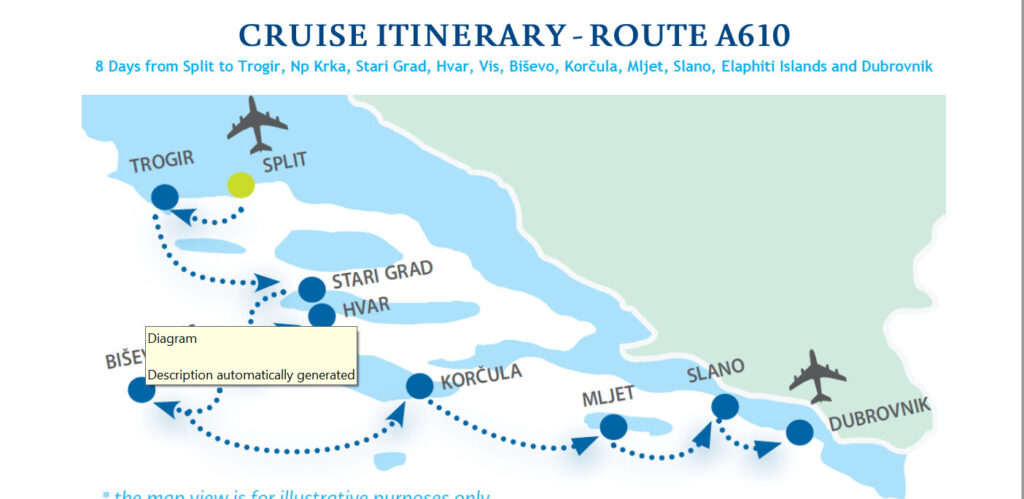

- A vacation + a disaster = an adventure.

- Ancient Jewish wisdom says not to argue to win the argument. Argue to discover the truth.

- The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.

- The best way to have good ideas is to have a lot of ideas and then discard the bad ideas.

- Seek to be the wisest in the room, not the loudest, and never miss a good chance to shut up.

- Never take down a fence until you know why it was put up.

- If you have to convince someone to stay with you, then they’ve already left.

- You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book is too difficult for adults, then write it for children.

- No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer. No surprise in the reader.

- Always apply the duck test.

- The past is behind, learn from it. The future is ahead, prepare for it. The present is here, live it.

- The two founding points of human existence are consciousness and entropy.

- Everything in moderation, including moderation.

- Read, read, read. Read everything—trash, classics, bad and good, and see how they do it. Just like a stonemason who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it. Then write. If it’s good, you’ll find out. If it’s not, throw it out the window and write something else.

- Carl Sagan said, “A book is made from a tree. It is an assemblage of flat, flexible parts (still called leaves) imprinted with dark pigmented squiggles. One glance at it and you’ll hear the voice of another person, perhaps a person who’s been dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, the author is speaking, clearly and silently, inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people, citizens of distant epochs, who never knew one another. Books break the shackles of time—proof that humans can work magic.”

- And Lady Gaga said, “When you make music or write or create, it’s really your job to have mind-blowing, irresponsible, condomless sex with whatever idea it is you’re writing about at the time.”

- There are old pilots and there are bold pilots but there are no old bold pilots.

- You don’t stop flying when you get old. You get old when you stop flying.

- A ride in a US Navy F-18 Hornet flight simulator is a mind-blowing and condomless, sexual experience. Been there. Done that. MUST do again.

- A business rule: Pay every invoice within 48 hours. You’ll be amazed at how many people give your work top priority.

- Ungulates like deer, moose, elk, and caribou have antlers for a reason.

- Bears have claws and teeth for a reason, too. Don’t poke the bear like I poked the badger.

- The cost of perfection is inaction, but boring progress produces exceptional results.

- The less you need the approval of others, the easier it is to get what is right rather than what is easy.

- “I don’t pay no attention to no kind of critics about nothing. If they knew as much as they claim about what they’re criticizing, then they ought to be doing that instead of standing on the sidelines using their mouth.” ~Muhammad Ali.

- Multitasking is not only not thinking, it impairs your ability to think. Thinking means concentrating on one thing long enough to develop an idea about it. You do your best thinking by slowing down and concentrating.

- Ninety percent of success can be boiled down to consistently doing the obvious thing for an uncommonly long time without convincing yourself that you’re smarter than you are.

- That thing that made you weird as a kid could make you great as an adult—provided you don’t lose it.

- If someone tries to convince you it’s not a pyramid scheme, it’s a pyramid scheme.

- If you have any doubts about your ability to carry a load in one trip, do yourself a favor and make two trips.

- Anything real begins with the fiction of what it could be. Imagination is the most potent force in the universe, and a skill you can get better at. It’s the one skill in life that benefits from ignoring what everyone else knows.

- For every dollar you spend on something substantial, expect to pay another dollar in repair, maintenance, and disposal fees by the end of its serviceable life.

- Eliminating clutter makes room for your true treasures.

- Art is in what you leave out.

- Never start a fight. Like, don’t get in a pissing match with a skunk, because you’re going to end up taking a tomato juice bath while the skunk reloads and carries on to defeat the next idiot.

- A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.

- People shouldn’t look for perfect leaders. They should look for authentic leaders with human-flawed competence and integrity, not consumed with presenting their title’s self-importance.

- Near the end of his life, Steve Jobs said, “I learned that life is like a river. At first, you think that if you’re successful, you get to take many things from that river… products people have made or ideas people have come up with. But, eventually, in life you realize that it’s not what you take from the river, it’s what you get to put into that river.”

- Everyone is entitled to their opinion, but not their facts.

- Learning is not compulsory. Neither is survival.

- When you die, you take nothing with you except your reputation.

Bonus Bit: When playing Monopoly, spend all you have to buy, barter, or trade for the strategic orange properties at the end of the second stretch just before Free Parking. Don’t bother with Utilities or Railroads.

——

What about you Kill Zoners? Whether you have more or less than 65 trips under your hat, how about sharing life bits you’ve found?

——

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over three decades of experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reincarnated as a crime writer who regularly contributes to the Kill Zone.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over three decades of experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reincarnated as a crime writer who regularly contributes to the Kill Zone.

Garry Rodgers also runs his own blog at DyingWords.net where he provokes thoughts on life, death, and writing. Check it out. You can also follow Garry at GarryRodgers1 on Twitter.

brought with us, so eerie doesn’t quite touch the atmosphere at zero-dark-early. We walked into the first one or two of the operatories, looked around, checked our watches and began talking about how we might work our way back to the bus.

brought with us, so eerie doesn’t quite touch the atmosphere at zero-dark-early. We walked into the first one or two of the operatories, looked around, checked our watches and began talking about how we might work our way back to the bus.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers.

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets Badass. One word, no hyphen.

Badass. One word, no hyphen. Bitch. Noun.

Bitch. Noun. SOB. Noun, capped with no periods.

SOB. Noun, capped with no periods. Asshat. Here’s a word that seems to be gaining in popularity in novels.

Asshat. Here’s a word that seems to be gaining in popularity in novels. Asshole. A noun, “usually vulgar.”

Asshole. A noun, “usually vulgar.” Let’s go to a fairly harmless phrase:

Let’s go to a fairly harmless phrase: LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE, my new Angela Richman mystery, is out. Publishers Weekly says, “Colorful characters match the crafty plot twists. Viets consistently entertains.” Read the review and order your copy here:

LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE, my new Angela Richman mystery, is out. Publishers Weekly says, “Colorful characters match the crafty plot twists. Viets consistently entertains.” Read the review and order your copy here:  For instance, I distinctly recall Betty Cutter, not Betty Crocker. She cut her own throat with her kitchen’s electric carving knife and her name was Elizabeth. Same with The Flying Dutchman— a guy named Hoogenstratten (sp?) who, with an alcohol level three times the legal driving limit, crashed his sizzled ultralight after buzzing into high-voltage power lines. Then there was Grizzly Adam whose name was Adam and was mauled to death by a grizzly bear.

For instance, I distinctly recall Betty Cutter, not Betty Crocker. She cut her own throat with her kitchen’s electric carving knife and her name was Elizabeth. Same with The Flying Dutchman— a guy named Hoogenstratten (sp?) who, with an alcohol level three times the legal driving limit, crashed his sizzled ultralight after buzzing into high-voltage power lines. Then there was Grizzly Adam whose name was Adam and was mauled to death by a grizzly bear. While Barb was messing with his head, I snooped around. It was typical digs for a single pensioner—a bachelor suite crammed with junk. Empty booze bottles and overflowing ashtrays testified to a lifestyle that suggested he should be dead of something by now. I checked for meds, which was routine. The pathologist would want to know what was likely in his system and the toxicology lab would want it for sure.

While Barb was messing with his head, I snooped around. It was typical digs for a single pensioner—a bachelor suite crammed with junk. Empty booze bottles and overflowing ashtrays testified to a lifestyle that suggested he should be dead of something by now. I checked for meds, which was routine. The pathologist would want to know what was likely in his system and the toxicology lab would want it for sure. Next morning my favorite pathologist, Dr. Elvira Esikanian, was on the roster to autopsy our guy from the kitchen floor. I loved dealing with Elvira. She’s Bosnian with a wicked sense of dry humor and an equally wicked curriculum vitae, including exhuming mass graves for the UN and serving in some of the busiest morgues around the world where she’d often do a dozen different cuttings per day.

Next morning my favorite pathologist, Dr. Elvira Esikanian, was on the roster to autopsy our guy from the kitchen floor. I loved dealing with Elvira. She’s Bosnian with a wicked sense of dry humor and an equally wicked curriculum vitae, including exhuming mass graves for the UN and serving in some of the busiest morgues around the world where she’d often do a dozen different cuttings per day. What I saw was a squiggling biological mass of sub-terrain aliens—looking out-of-this-world like agitated, animated, turquoise tampons breathlessly mingling in a magnified mess of greenish-gray snot.

What I saw was a squiggling biological mass of sub-terrain aliens—looking out-of-this-world like agitated, animated, turquoise tampons breathlessly mingling in a magnified mess of greenish-gray snot. Realizing the lethality of the situation and the danger to others, Barb and I immediately went back to the apartment. There, on the counter, was a jar of red pepper paste with a label indicating it originated in China and was far past its expiry date. A tag showed it’d been purchased at the Dollar Store.

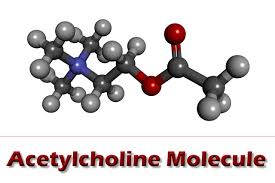

Realizing the lethality of the situation and the danger to others, Barb and I immediately went back to the apartment. There, on the counter, was a jar of red pepper paste with a label indicating it originated in China and was far past its expiry date. A tag showed it’d been purchased at the Dollar Store. In the case of a muscle contraction, the chemical signal is passed using a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. This sits in the neuron in a vesicle, a small bubble surrounded by a membrane, until it is required. When the neuron receives a message from the nervous system to initiate a muscle contraction, the acetylcholine is released from the vesicle and passes through the synapse into the muscle fiber.

In the case of a muscle contraction, the chemical signal is passed using a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. This sits in the neuron in a vesicle, a small bubble surrounded by a membrane, until it is required. When the neuron receives a message from the nervous system to initiate a muscle contraction, the acetylcholine is released from the vesicle and passes through the synapse into the muscle fiber. The same gruesome stuff in the red pepper paste that painfully killed our old man is commonly stuck into people’s faces to make them look younger and pretty.

The same gruesome stuff in the red pepper paste that painfully killed our old man is commonly stuck into people’s faces to make them look younger and pretty. Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner. Now he’s reinvented himself as a crime writer and deadly blogger. Probably an upcoming podcaster, too. 😉

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner. Now he’s reinvented himself as a crime writer and deadly blogger. Probably an upcoming podcaster, too. 😉